Pilgrimage of Grace

The "most serious of all Tudor period rebellions", it was a protest against Henry VIII's break with the Catholic Church, the dissolution of the lesser monasteries, and the policies of the King's chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, as well as other specific political, social, and economic grievances.

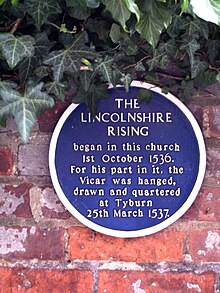

[2] Following the suppression of the short-lived Lincolnshire Rising of 1536, the traditional historical view portrays the Pilgrimage as "a spontaneous mass protest of the conservative elements in the North of England angry with the religious upheavals instigated by King Henry VIII".

[6] On 30 September 1536, Dr. John Raynes, Chancellor of the Diocese of Lincoln, and one of Cromwell's commissioners, was addressing the assembled clergy in Bolingbroke, informing them of the new regulations and taxes affecting them.

One of his clerks further inflamed matters regarding new requirements for the academic standards of the clergy saying "Look to your books, or there will be consequences",[7] which may have worried some of the less educated attendees.

Dr. John Raynes, the chancellor of the Diocese of Lincoln, who was ill at Bolingbroke, was dragged from his sick-bed in the chantry priests' residence and later beaten to death by the mob, and the commissioners' registers were seized and burned.

[9]: 56 The protest effectively ended on 4 October 1536, when the King sent word for the occupiers to disperse or face the forces of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, which had already been mobilised.

Following the rising, the vicar of Louth and Captain Cobbler, two of the main leaders, were captured and hanged at Tyburn.

[5] Most of the other local ringleaders were executed during the next 12 days, including William Moreland, or Borrowby, one of the former Louth Park Abbey monks.

Henry VIII was also in the habit of raising more funds for the crown through taxation, confiscation of lands, and depreciating the value of goods.

A great deal of the taxation was levied against property and income, especially in the areas around Cumberland and Westmoreland where accounts of extortionate rents and gressums, a payment made to the crown when taking up a tenancy through inheritance, sale, or entry fines, were becoming more and more common.

[13] Although her successor, Anne Boleyn, had been unpopular as Catherine's replacement as a rumoured Protestant, her execution in 1536 on charges of adultery and treason had done much to undermine the monarchy's prestige and the King's personal reputation.

The recently released Ten Articles and the new order of prayer issued by the government in 1535 had also made official doctrine more Protestant, which went against the Catholic beliefs of most northerners.

[14][15] He arranged for expelled monks and nuns to return to their houses; the King's newly installed tenants were driven out, and Catholic observances were resumed.

[17] However, the rising was so successful that the royalist leaders, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and George Talbot, 4th Earl of Shrewsbury, opened negotiations with the insurgents at Scawsby Leys, near Doncaster, where Aske had assembled between 30,000 and 40,000 people.

[16] In early December 1536, the Pilgrimage of Grace gathered at Pontefract Castle to draft a petition to be presented to King Henry VIII with a list of their demands.

The loss of the leaders enabled the Duke of Norfolk to quell the rising,[16] and martial law was imposed upon the demonstrating regions.

[18] The details of the trial and execution of major leaders were recorded by the author of Wriothesley's Chronicle:[9]: 63-4 [19][2] Also the 16-day of May [1537] there were arraigned at Westminster afore the King’s Commissioners, the Lord Chancellor that day being the chief, these persons following: Sir Robert Constable, knight; Sir Thomas Percy, knight, and brother to the Earl of Northumberland; Sir John Bulmer, knight, and Ralph Bulmer, his son and heir; Sir Francis Bigod, knight; Margaret Cheney, after Lady Bulmer by untrue matrimony; George Lumley, esquire;[20] Robert Aske, gentleman, that was captain in the insurrection of the Northern men; and one Hamerton, esquire, all which persons were indicted of high treason against the King, and that day condemned by a jury of knights and esquires for the same, whereupon they had sentence to be drawn, hanged and quartered, but Ralph Bulmer, the son of John Bulmer, was reprieved and had no sentence.

And the same day Margaret Cheney, 'other wife to Bulmer called', was drawn after them from the Tower of London into Smithfield, and there burned according to her judgment, God pardon her soul, being the Friday in Whitsun week; she was a very fair creature, and a beautiful.The Lincolnshire Rising and the Pilgrimage of Grace have historically been seen as failures for the following reasons: Their partial successes are less known: Historians have noted the leaders among the nobility and gentry in the Lincolnshire Rising and the Pilgrimage of Grace and tend to argue that the Risings gained legitimacy only through the involvement of the northern nobility and gentlemen, such as Lord Darcy, Lord Hussey and Robert Aske.

The nobles hid behind the force of the lower classes with claims of coercion, since they were seen as blameless for their actions because they did not possess political choice.