English Reformation

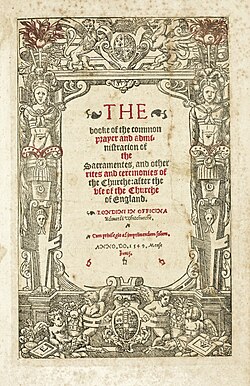

The theology and liturgy of the Church of England became markedly Protestant during the reign of Henry's son Edward VI (1547–1553) largely along lines laid down by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

These events were part of the wider European Reformation: various religious and political movements that affected both the practice of Christianity in Western and Central Europe and relations between church and state.

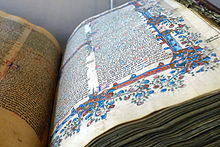

[18] Some Renaissance humanists, such as Erasmus (who lived in England for a time), John Colet and Thomas More, called for a return ad fontes ("back to the sources") of Christian faith—the scriptures as understood through textual, linguistic, classical and patristic scholarship[19]—and wanted to make the Bible available in the vernacular.

[24][25] Early Protestants portrayed Catholic practices such as confession to priests, clerical celibacy, and requirements to fast and keep vows as burdensome and spiritually oppressive.

[39] Catherine had been his late brother's wife, and it was therefore against biblical teachings for Henry to have married her (Leviticus 20:21); a special dispensation from Pope Julius II had been needed to allow the wedding in the first place.

Clement also feared the wrath of Catherine's nephew, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, whose troops earlier that year had sacked Rome and briefly taken the Pope prisoner.

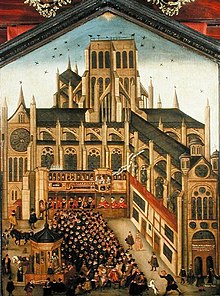

[58] To address this issue, Parliament passed the Act in Restraint of Appeals, which outlawed appeals to Rome on ecclesiastical matters and declared that This realm of England is an Empire, and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one Supreme Head and King having the dignity and royal estate of the Imperial Crown of the same, unto whom a body politic compact of all sorts and degrees of people divided in terms and by names of Spirituality and Temporality, be bounden and owe to bear next to God a natural and humble obedience.

[citation needed] The break with Rome gave Henry VIII power to administer the English Church, tax it, appoint its officials, and control its laws.

[107] Later that year, Parliament passed the Six Articles reaffirming the Catholic beliefs and practices such as transubstantiation, clerical celibacy, confession to a priest, votive masses, and withholding communion wine from the laity.

Different reasons were advanced: that Cromwell would not enforce the Act of Six Articles; that he had supported Robert Barnes, Hugh Latimer and other heretics; and that he was responsible for Henry's marriage to Anne of Cleves, his fourth wife.

French diplomat Charles de Marillac wrote that Henry's religious policy was a "climax of evils" and that: [I]t is difficult to have a people entirely opposed to new errors which does not hold with the ancient authority of the Church and of the Holy See, or, on the other hand, hating the Pope, which does not share some opinions with the Germans.

Henry expressed his fears to Parliament in 1545 that "the Word of God, is disputed, rhymed, sung and jangled in every ale house and tavern, contrary to the true meaning and doctrine of the same.

While Henry's motives were largely financial (England was at war with France and desperately in need of funds), the passage of the Chantries Act was "an indication of how deeply the doctrine of purgatory had been eroded and discredited".

A. G. Dickens contended that people had "ceased to believe in intercessory masses for souls in purgatory",[148] but Eamon Duffy argued that the demolition of chantry chapels and the removal of images coincided with the activity of royal visitors.

[181] Edmund Bonner of London, William Rugg of Norwich, Nicholas Heath of Worcester, John Vesey of Exeter, Cuthbert Tunstall of Durham, George Day of Chichester and Stephen Gardiner of Winchester were either deprived of their bishoprics or forced to resign.

[185][183] The newly enlarged and emboldened Protestant episcopate turned its attention to ending efforts by conservative clergy to "counterfeit the popish mass" through loopholes in the 1549 prayer book.

[179][189] During his consecration as bishop of Gloucester, John Hooper objected to the mention of "all saints and the holy Evangelist" in the Oath of Supremacy and to the requirement that he wear a black chimere over a white rochet.

[193] Anglican bishop and scholar Colin Buchanan interprets the prayer book to teach that "the only point where the bread and wine signify the body and blood is at reception".

[198] These fears were confirmed in March 1551 when the Privy Council ordered the confiscation of church plate and vestments "for as much as the King's Majestie had neede [sic] presently of a mass of money".

The Forty-two Articles reflected the Reformed theology and practice taking shape during Edward's reign, which historian Christopher Haigh describes as a "restrained Calvinism".

"[212] Following Mary's accession, the Duke of Norfolk along with the conservative bishops Bonner, Gardiner, Tunstall, Day and Heath were released from prison and restored to their former dioceses.

[216] There were disappointments for Mary: Parliament refused to penalise non-attendance at Mass, would not restore confiscated church property, and left open the question of papal supremacy.

"[219] In response, Parliament submitted a petition to the Queen the next day asking that "this realm and dominions might be again united to the Church of Rome by the means of the Lord Cardinal Pole".

[222] The historian Eamon Duffy writes that the Marian religious "programme was not one of reaction but of creative reconstruction" absorbing whatever was considered positive in the reforms of Henry VIII and Edward VI.

[225] Cardinal Pole himself was a member of the Spirituali, a Catholic reform movement that shared with Protestants an emphasis on man's total dependence on God's grace by faith and Augustinian views on salvation.

Modelled on the King's Book of 1543, Bonner's work was a survey of basic Catholic teaching organized around the Apostles' Creed, Ten Commandments, seven deadly sins, sacraments, the Lord's Prayer, and the Hail Mary.

[232] From December 1555 to February 1556, Cardinal Pole presided over a national legatine synod that produced a set of decrees entitled Reformatio Angliae or the Reformation of England.

Some modifications were made to appeal to Catholics and Lutherans, including giving individuals greater latitude concerning belief in the real presence and authorising the use of traditional priestly vestments.

[270] The influx of foreign trained Catholic priests, the unsuccessful Revolt of the Northern Earls, the excommunication of Elizabeth, and the discovery of the Ridolfi plot all contributed to a perception that Catholicism was treasonous.

[280] During the early Stuart period, the Church of England's dominant theology was still Calvinism, but a group of theologians associated with Bishop Lancelot Andrewes disagreed with many aspects of the Reformed tradition, especially its teaching on predestination.