English coffeehouses in the 17th and 18th centuries

The historian Brian Cowan describes English coffeehouses as "places where people gathered to drink coffee, learn the news of the day, and perhaps to meet with other local residents and discuss matters of mutual concern.

Historians often associate English coffeehouses, during the 17th and 18th centuries, with the intellectual and cultural history of the Age of Enlightenment: they were an alternate sphere, supplementary to the university.

[2] According to Markman Ellis, travellers accounted for how men would consume an intoxicating liquor, "black in colour and made by infusing the powdered berry of a plant that flourished in Arabia.

[5] As such, through Cowan's evaluation of the English virtuosi's utilitarian project for the advancement of learning involving experiments with coffee, this phenomenon is well explained.

[6] Sir Francis Bacon was an important English virtuoso whose vision was to advance human knowledge through the collection and classification of the natural world in order to understand its properties.

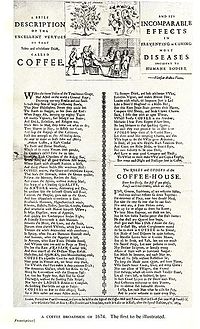

These experimentalists feared that excessive coffee consumption could result in languor, paralysis, heart conditions and trembling limbs, as well as low spiritedness and nervous disorders.

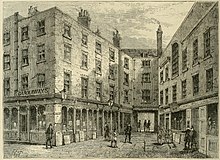

[10] You have all Manner of News there: You have a good Fire, which you may sit by as long as you please: You have a Dish of Coffee; you meet your Friends for the Transaction of Business, and all for a Penny, if you don't care to spend more.

A ripe location for just such an enterprise was the city of Oxford, with its unique combination of exotic scholarship interests and energetic experimental community.

[17] Early Oxford coffeehouse virtuosi included Christopher Wren, Peter Pett, Thomas Millington, Timothy Baldwin, and John Lamphire, to name a few.

"The coffeehouse was a place for "virtuosi" and "wits", rather than for the plebes or roués who were commonly portrayed as typical patrons of the alcoholic drinking houses.

Pasqua Rosée, a native of Smyrna, western Turkey of a Levant Company merchant named Daniel Edwards, established the first London coffeehouse[19][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28] in 1652.

This club was also a "free and open academy unto all comers" whose raison d'être was the art of debate, characterised as "contentious but civil, learned but not didactic.

Ellis explains: "Londoners could not be entirely subdued and there were still some who climbed the narrow stairs to their favourite coffeehouses although no longer prepared to converse freely with strangers.

Before entering they looked quite around the room, and would not approach even close acquaintances without first inquiring the health of the family at home and receiving assurances of their well-being.

"[38] Some historians even claimed that these institutions acted as democratic bodies due to their inclusive nature: "Whether a man was dressed in a ragged coat and found himself seated between a belted earl and a gaitered bishop it made no difference; moreover he was able to engage them in conversation and know that he would be answered civilly.

[40] Cowan applies the term "civility" to coffeehouses in the sense of "a peculiarly urban brand of social interaction which valued sober and reasoned debate on matters of great import, be they scientific, aesthetic, or political.

[44] Ellis explains that because Puritanism influenced English coffeehouse behaviorisms, intoxicants were forbidden, allowing for respectable sober conversation.

The arrival of coffee triggered a dawn of sobriety that laid the foundations for truly spectacular economic growth in the decades that followed as people thought clearly for the first time.

[dubious – discuss] The stock exchange, insurance industry, and auctioneering: all burst into life in 17th-century coffeehouses — in Jonathan's, Lloyd's, and Garraway's — spawning the credit, security, and markets that facilitated the dramatic expansion of Britain's network of global trade in Asia, Africa and America.

[53] In the 17th century, stockbrokers also gathered and traded in coffee houses, notably Jonathan's Coffee-House, because they were not allowed in the Royal Exchange due to their rude manners.

As these anecdotal stories held underlying, rather than explicit, social critiques, "readers were persuaded, not coerced, into freely electing these standards of taste and behaviour as their own.

[66] According to Habermas, this 'public realm' "is a space where men could escape from their roles as subjects, and gain autonomy in the exercise and exchange of their own opinions and ideas.

She justifies her placement of English coffeehouses within an 'intellectual public sphere' by naming them "commercial operations, open to all who could pay and thus provided ways in which many different social strata could be exposed to the same ideas.

[68] According to Outram, as English coffeehouses offered various forms of print items, such as newspapers, journals and some of the latest books, they are to be considered within the public sphere of the Enlightenment.

[69] Historian James Van Horn Melton offers another perspective and places English coffeehouses within a more political public sphere of the Enlightenment.

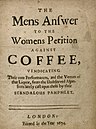

"[75] They protested against the consumption of coffee arguing that it made men sterile and impotent and stated that it contributed to the nation's failing birth rate.

"[78] In addition, as McDowell's study shows, female hawkers "shap[ed] the modes and forms of political discourse through their understanding of their customer's desires for news and print ephemera.

Ellis explains: "Ridicule and derision killed the coffee-men's proposal but it is significant that, from that date, their influence, status and authority began to wane.

[84] In regards to the decline in coffee culture, Ellis concludes: "They had served their purpose and were no longer needed as meeting-places for political or literary criticism and debate.

They had seen the nation pass through one of its greatest periods of trial and tribulation; had fought and won the battle age of profligacy; and had given us a standard of prose-writing and literary criticism unequalled before or since.