English-language learner

In opposition to this, cases like Castaneda v Pickard fought for educational equality and standards focused on developing ELL students, as well as an overall sound plan for school districts.

To combat this, education advocates in the Bay Area began to open all-inclusive schools to promote the acceptance of ELL students.

In transition-bilingual programs, instruction begins in the student's native language and then switches to English in elementary or middle school.

[12] In schools using a push-in style of teaching, educators disagree over whether ELL students should be encouraged or permitted to participate in additional foreign language classes, such as French.

[14] In a five-week study by J. Huang, research showed that "classroom instruction appeared to play an important role in integrating language skills development and academic content learning."

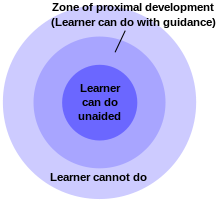

All of these additional areas of support are to be gradually removed, so that students become more independent, even if that means no longer needing some of these associations or seeking them out for themselves.

In Asao Inoue's "Labor-Based Grading Contracts", he proposes an alternative to traditional content-based or quality-based methods of assessment in writing classrooms.

The Every Student Succeeds Act or ESSA passed in 2015 requires all ELLs attending public schools from grades K–12 to be assessed in multiple language domains, such as listening, reading, writing, and speaking.

[22] This lack of variety in assessments may restrict teachers' ability to accurately determine the academic progress of a student and introduce biases that may result in lower test scores.

A combination of misinformation, stereotypes, and individual reservations can alter teachers' perception when working with culturally diverse or non-native English speakers.

From a Walden University study, a handful of teachers at an elementary school expressed not having the energy, training, or time to perform for these students.

Another reason that an ESL student may be struggling to join discussions and engage in class could be attributed to whether they come from a culture where speaking up to an authority figure (like a teacher or a professor) is discouraged.

Strategies that can mitigate this discomfort or misunderstanding of expectations include offering surveys or reflective writing prompts, that are collected after class, inquiring about student's educational and cultural backgrounds and past learning experiences.

[24] Aside from linguistic gaps, the adjustment to American scholarly expectations, writing genres, and prompts can all be jarring and even contradictory to an ELL individual's academic experiences from their home country.

Many collegiate ELLs can be overwhelmed and confused by all of the additional information, making it difficult to decipher all of the different parts that their writing needs to address.

Another example is found in how students from other countries may be unfamiliar with sharing their opinions,[37] or criticizing the government in any form,[38] even if this is a requirement for an essay or a speech.

According to a survey by Lin (2015), "Many [ELL students] indicated that they had problems adjusting their ways of writing in their first language to American thought patterns.

[21][45]Information from standardized tests, direct observation, and parent feedback are used to diagnose the root causes for language learning students who struggle with academics.

[46] When classifying the disability or impairment, the intrinsic and extrinsic factors considered are: To maintain an environment that is beneficial for both the teacher and the student, culture, literature, and other disciplines should be integrated systematically into the instruction.

Postponing content-area instruction until CLD students gain academic language skills bridges the linguistic achievement gap between the learners and their native-English speaking peers.

[47] By integrating other disciplines into the lesson, it will make the content more significant to the learners and will create higher order thinking skills across the areas.

Viewing these activities can help English-language learners develop an understanding of new concepts while at the same time building topic related schema (background knowledge).

[53] Introducing students to media literacy and accessible materials can also aid them in their future academic endeavors and establish research skills early on.

[54] This can include activities such as science experiments and art projects, which are tactile ways that encourage students to create solutions to proposed problems or tasks.

To respond to deficiencies in the public school system, educators and student activists have created spaces that work to uplift ELL and their families.

Labeled as family-school-community partnerships, these spaces have sought out cultural and linguistic responsiveness through encouraging participation and addressing needs outside of school.

[55] While there have been several advancements in both the rights and the strategies and support offered in the United States and Canada for English-language learning students, there is still much work to be done.

Adoption of socially-just classroom pedagogies such as those proposed by Asao Inoue, and the re-examination of the privileges inherent in the existence of "Standard Academic English" are current steps towards a trajectory of inclusion and tolerance for these groups of students in both K–12 and higher education.