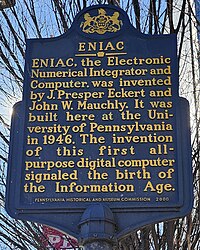

ENIAC

[11] ENIAC was formally dedicated at the University of Pennsylvania on February 15, 1946, having cost $487,000 (equivalent to $6,900,000 in 2023), and called a "Giant Brain" by the press.

ENIAC's design and construction was financed by the United States Army, Ordnance Corps, Research and Development Command, led by Major General Gladeon M.Barnes.

[14] The conception of ENIAC began in June 1941, when Friden calculators and differential analyzers were used by the United States Army Ordnance Department to compute firing tables for artillery, which was done by graduate students under John Mauchly's supervision.

[17] The construction contract was signed on June 5, 1943; work on the computer began in secret at the University of Pennsylvania's Moore School of Electrical Engineering[18] the following month, under the code name "Project PX", with John Grist Brainerd as principal investigator.

Later in November of that year, the duo, along with John Brainerd and Herman Goldstine, issued the first confidential published report on the computer, which talks about how it worked and the methods by which it was programmed.

[16] ENIAC was designed by Ursinus College physics professor John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert of the University of Pennsylvania, U.S.[21] The team of design engineers assisting the development included Robert F. Shaw (function tables), Jeffrey Chuan Chu (divider/square-rooter), Thomas Kite Sharpless (master programmer), Frank Mural (master programmer), Arthur Burks (multiplier), Harry Huskey (reader/printer) and Jack Davis (accumulators).

[22] Significant development work was undertaken by the female mathematicians who handled the bulk of the ENIAC programming: Jean Jennings, Marlyn Wescoff, Ruth Lichterman, Betty Snyder, Frances Bilas, and Kay McNulty.

In order to achieve its high speed, the panels had to send and receive numbers, compute, save the answer and trigger the next operation, all without any moving parts.

Key to its versatility was the ability to branch; it could trigger different operations, depending on the sign of a computed result.

By the end of its operation in 1956, ENIAC contained 18,000 vacuum tubes, 7,200 crystal diodes, 1,500 relays, 70,000 resistors, 10,000 capacitors, and approximately 5,000,000 hand-soldered joints.

ENIAC used common octal-base radio tubes of the day; the decimal accumulators were made of 6SN7 flip-flops, while 6L7s, 6SJ7s, 6SA7s and 6AC7s were used in logic functions.

[45] During World War II, while the U.S. Army needed to compute ballistics trajectories, many women were interviewed for this task.

[49] These early programmers were drawn from a group of about two hundred women employed as computers at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania.

The job of computers was to produce the numeric result of mathematical formulas needed for a scientific study, or an engineering project.

[23] Under Herman and Adele Goldstine's direction, the computers studied ENIAC's blueprints and physical structure to determine how to manipulate its switches and cables, as programming languages did not yet exist.

The labor shortage created by World War II helped enable the entry of women into the field.

[23] For example, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics said in 1942, "It is felt that enough greater return is obtained by freeing the engineers from calculating detail to overcome any increased expenses in the computers' salaries.

This is due in large measure to the feeling among the engineers that their college and industrial experience is being wasted and thwarted by mere repetitive calculation.

Scientists involved in the original nuclear bomb development used massive groups of people doing huge numbers of calculations ("computers" in the terminology of the time) to investigate the distance that neutrons would likely travel through various materials.

Elizabeth Snyder and Betty Jean Jennings were responsible for developing the demonstration trajectory program, although Herman and Adele Goldstine took credit for it.

None of the women involved in programming the machine or creating the demonstration were invited to the formal dedication nor to the celebratory dinner held afterwards.

There, on July 29, 1947, it was turned on and was in continuous operation until 11:45 p.m. on October 2, 1955, when it was retired in favor of the more efficient EDVAC and ORDVAC computers.

[2] A few months after ENIAC's unveiling in the summer of 1946, as part of "an extraordinary effort to jump-start research in the field",[69] the Pentagon invited "the top people in electronics and mathematics from the United States and Great Britain"[69] to a series of forty-eight lectures given in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; all together called The Theory and Techniques for Design of Digital Computers—more often named the Moore School Lectures.

Von Neumann wrote up an incomplete set of notes (First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC) which were intended to be used as an internal memorandum—describing, elaborating, and couching in formal logical language the ideas developed in the meetings.

ENIAC administrator and security officer Herman Goldstine distributed copies of this First Draft to a number of government and educational institutions, spurring widespread interest in the construction of a new generation of electronic computing machines, including Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC) at Cambridge University, England and SEAC at the U.S. Bureau of Standards.

ENIAC was, like the IBM Harvard Mark I and the German Z3, able to run an arbitrary sequence of mathematical operations, but did not read them from a tape.

Work on the ABC at Iowa State University was stopped in 1942 after John Atanasoff was called to Washington, D.C., to do physics research for the U.S. Navy, and it was subsequently dismantled.

[95][96] The public demonstration for ENIAC was developed by Snyder and Jennings who created a demo that would calculate the trajectory of a missile in 15 seconds, a task that would have taken several weeks for a human computer.

[52] For a variety of reasons – including Mauchly's June 1941 examination of the Atanasoff–Berry computer (ABC), prototyped in 1939 by John Atanasoff and Clifford Berry – U.S. patent 3,120,606 for ENIAC, applied for in 1947 and granted in 1964, was voided by the 1973[97] decision of the landmark federal court case Honeywell, Inc. v. Sperry Rand Corp..

[53][108] The role of the ENIAC programmers is treated in a 2010 documentary film titled Top Secret Rosies: The Female "Computers" of WWII by LeAnn Erickson.