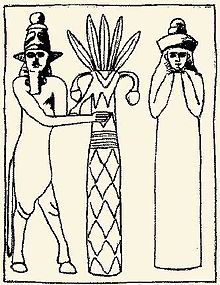

Enlil and Ninlil

The first lines of the myth were discovered on the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, catalogue of the Babylonian section (CBS), tablet number 9205 from their excavations at the temple library at Nippur.

This was translated by George Aaron Barton in 1918 and first published as "Sumerian religious texts" in "Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions", number seven, entitled "A Myth of Enlil and Ninlil".

He also included translations from tablets in the Nippur collection of the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul, catalogue number 2707.

[4][5] Another tablet used as cuneiform source for the myth is held by the British Museum, BM 38600, details of which were published in 1919.

[7] The story opens with a description of the city of Nippur, its walls, river, canals and well, portrayed as the home of the gods and, according to Kramer "that seems to be conceived as having existed before the creation of man."

[8] This conception of Nippur is echoed by Joan Goodnick Westenholz, describing the setting as "civitas dei", existing before the "axis mundi".

"[10]The story continues by introducing the goddess Nun-bar-she-gunu warning her daughter Ninlil about the likelihood of romantic advances from Enlil if she strays too near the river.

Ninlil resists Enlil's first approach after which he entreats his minister Nuska to take him across the river, on the other side the couple meet and float downstream, either bathing or in a boat, then lie on the bank together, kiss, and conceive Suen-Ashimbabbar,[11] the moon god.

The story then cuts to Enlil walking in the Ekur, where the other gods arrest him for his relationship with Ninlil and exile him from the city for being ritually impure.

"[10]Jeremy Black discusses the problems of serial pregnancy and multiple births along with the complex psychology of the myth.

"[13] Robert Payne has suggested that the initial scene of the courtship takes place on the bank of a canal instead of a river.

[14] Herman Behrens has suggested a ritual context for the myth where dramatic passages were acted out on a voyage between the Ekur and the sanctuary in Nippur.

He concludes that the narrative exonerates Enlil and Ninlil indicating nature to have its way even where societal conventions try to contain sexual desire.