Hymn to Enlil

[1] Fragments of the text were discovered in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology catalogue of the Babylonian section (CBS) from their excavations at the temple library at Nippur.

The myth was first published using tablet CBS 8317, translated by George Aaron Barton in 1918 as "Sumerian religious texts" in "Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions", number ten, entitled "An excerpt from an exorcism".

[4] He also worked with Samuel Noah Kramer to publish three other tablets CBS 8473, 10226, 13869 in "Sumerian texts of varied contents" in 1934.

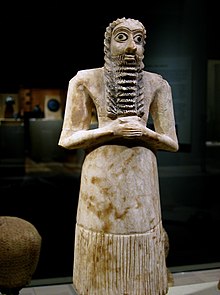

All the gods of the earth bow down to father Enlil, who sits comfortably on the holy dais, the lofty engur, to Nunamnir, whose lordship and princeship are most perfect.

[7]The hymn develops by relating Enlil founding and creating the origin of the city of Nippur and his organization of the earth.

Its soil is the life of the land (Sumer)[1]The hymn moves on from the physical construction of the city and gives a description and veneration of its ethics and moral code: The powerful lord, who is exceedingly great in heaven and earth, who knows judgement, who is wise.

"[18] The myth continues with the city's inhabitants building a temple dedicated to Enlil, referred to as the Ekur.

The priestly positions and responsibilities of the Ekur are listed along with an appeal for Enlil's blessings on the city, where he is regarded as the source of all prosperity: Without the Great Mountain, Enlil, no city would be built, no settlement would be founded; no cow-pen would be built, no sheepfold would be established; no king would be elevated, no lord would be given birth; no high priest or priestess would perform extispicy; soldiers would have no generals or captains; no carp-filled waters would ... the rivers at their peak; the carp would not ... come straight up from the sea, they would not dart about.

The sea would not produce all its heavy treasure, no freshwater fish would lay eggs in the reedbeds, no bird of the sky would build nests in the spacious land; in the sky the thick clouds would not open their mouths; on the fields, dappled grain would not fill the arable lands, vegetation would not grow lushly on the plain; in the gardens, the spreading forests of the mountain would not yield fruits.

Without the Great Mountain, Enlil, Nintud would not kill, she would not strike dead; no cow would drop its calf in the cattle-pen, no ewe would bring forth ... lamb in its sheepfold; the living creatures which multiply by themselves would not lie down in their ... ; the four-legged animals would not propagate, they would not mate.

[22] Joan Westenholz noted that "The farmer image was even more popular than the shepherd in the earliest personal names, as might be expected in an agrarian society."

[23] The term appears in line sixty Its great farmer is the good shepherd of the Land, who was born vigorous on a propitious day.

In the hymn to Enlil, its interior is described as a 'distant sea': Its (Ekur's) me's (ordinances) are mes of the Abzu which no-one can understand.

[24]The foundations of Enlil's temple are made of lapis lazuli, which has been linked to the "soham" stone used in the Book of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 28:13) describing the materials used in the building of "Eden, the Garden of god" perched on "the mountain of the lord", Zion, and in the Book of Job (Job 28:6–16) "The stones of it are the place of sapphires and it hath dust of gold".

Precious stones are also later repeated in a similar context describing decoration of the walls of New Jerusalem in the Apocalypse (Revelation 21:21).