Environmental history of Latin America

According to one assessment of the field, scholars have mainly been concerned with "three categories of research: colonialism, capitalism, and conservation" and the analysis focuses on narratives of environmental decline.

[8][9] Works by geographers and other scholars began focusing on humans and the environmental context, especially Carl O. Sauer at University of California, Berkeley.

[10][11] Other early scholars examining humans and nature interactions, such as William Denevan, Julian Steward, Eric Wolf, and Claude Lévi-Strauss.

In terms of impact, however, Alfred W. Crosby's The Columbian Exchange (1972) was a major work, one of the first to deal with profound environmental changes touched off by European settlement in the New World.

[12] Archeologists such as Richard MacNeish conducted fieldwork uncovering the origins of agriculture in Mesoamerica and in the Andes, giving a long timeline for the human-wrought changes in the environment before the arrival of the Europeans.

[15] Works by archeologists and historians focusing on the colonial era in Latin America (1492-1825), which were not called “environmental history” at the time, are a rejoinder to that criticism.

These surpluses allowed for social differentiation and hierarchy, large settlements with monumental architecture, and political states that could demand labor and tribute from growing populations.

[19][20] By the time Spaniards began exploring Central America in the early sixteenth century, there were 600 years of jungle growth and only ruins of the monumental structures, but the human populations persisted in smaller numbers and scattered settlements, practicing subsistence agriculture.

In areas not suitable to sedentary agriculture, there were usually small bands of people, often extended kin groups, who pursued hunting and gathering on a gendered basis.

With the deliberate importation of Old World plants and animals and the unintentional spread of diseases brought by the Europeans (smallpox, measles, and others) changed the natural environment in many parts of Latin America.

The Europeans’ demand for pearls increased and the careful and selective indigenous methods gave way to Spaniards’ wholesale destruction of the oyster beds with dredges.

Unknown to them was the environmental conditions that pearl oysters needed for produce their treasure – proper salinity and temperature of the water and the optimal type of sea bottom.

[22][23] The search for a high value export product also resulted in Spaniards introducing cane sugar cultivation and the importation of African slaves as the main labor force.

African slaves were forcibly brought in the early the 1500s and sugar plantations were established on the island of Hispaniola (now divided between Haiti and the Dominican Republic).

[24] Cane sugar became the main export product from Portuguese Brazil and on Caribbean islands that other European powers seized from Spain.

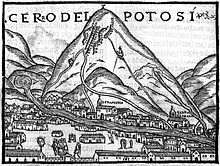

[25] In both Mexico and Peru, the introduction of mercury amalgam to process ore resulted in the revival of mining and more insidious and long-term environmental impacts.

In the eighteenth century, the Spanish crown calculated that lowering the cost of mercury to miners in Mexico would result in higher silver output.

[26] When mercury was discovered in significant amounts at Huancavelica, Peru's silver mining industry could regain its previous levels of output.

However, since the mercury was volatilized in silver ore processing and only partially recaptured, its impact on larger human and animal populations was more widespread since it can be absorbed by breathing.

The toxic impact results in nerve damage, inducing muscle deterioration and mental disorders, infertility, birth defects, asthma, and chronic fatigue, to name just a few.

[28] In general, the presence or absence of sufficient water was a major determinant of where human settlement would occur in the pre-industrial Latin America.

Before the Spanish conquest in 1521, the Aztecs had constructed an aqueduct from a spring at Chapultepec (“hill of the grasshopper”) to Tenochitlan to provide freshwater to the urban population of nearly 100,000.

The aqueduct was constructed using wood, carved stone, and compacted soil, with portions made of hollowed logs, allowing canoes to travel underneath.

Wool was a major economic resource for the domestic cloth market in Mexico, so sheep ranching expanded during the colonial era, in many cases leaving ecological destruction.

For Peru, huge deposits of bird guano on the Chincha islands off its coast provided revenue for the Peruvian state, facilitating its post-independence consolidation.

Warren Dean's 1997 book With Broadax and Firebrand: The Destruction of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest was written as an environmental history of Brazil.

The Costa Rican government contracted with Minor Cooper Keith to build a railway to the Gulf Coast port of Limón.

Although exploitative of labor, the industry was a form of resource extraction that did not result in deforestation or destruction of the trees, which could tolerate the latex tapping.

Bananas are relatively easy to grow in the tropics where there is sufficient water, but it could not become a major export crop until it could be brought to market quickly and sold cheaply to consumers.

Keith received land along the railway in partial compensation, which when cleared he turned into extensive banana cultivation of the Gros Michel (“Big Mike”) (Musa acuminate) variety in monoculture.