Epidemiological transition

In demography and medical geography, epidemiological transition is a theory which "describes changing population patterns in terms of fertility, life expectancy, mortality, and leading causes of death.

[4][5] Omran divided the epidemiological transition of mortality into three phases, in the last of which chronic diseases replace infection as the primary cause of death.

The theory of epidemiological transition uses patterns of health and disease as well as their forms of demographic, economical and sociological determinants and outcomes.

Today, life expectancy in developing countries remains relatively low, as in many Sub-Saharan African nations where it typically doesn't exceed 60 years of age.

[8] The second phase involves improved nutrition as a result of stable food production along with advances in medicine and the development of health care systems.

Mortality in Western Europe and North America was halved during the 19th century due to closed sewage systems and clean water provided by public utilities, with a particular benefit for children of both sexes and to females in the adolescent and reproductive age periods, probably because the susceptibility of these groups to infectious and deficiency diseases is relatively high.

[4] The transition may also be associated with demographic movements to urban areas, and a shift from agriculture and labor-based production output to technological and service-sector-based economies.

This shift in demographic and disease profiles is currently under way in most developing nations, however every country is unique and transition speed is based on numerous geographical and sociopolitical factors.

Whether the transition is due to socioeconomic improvements (as in developed countries) or by modern public health programs (as has been the case in many developing countries), the lowering of mortality and of infectious disease tends to increase economic productivity through better functioning of adult members of the labor force and through an increase in the proportion of children who survive and mature into productive members of society.

Decomposing this overall impact by age-sex groups, they find that for males, when overall mortality decreases, the importance of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) increases relative to the other causes with an age-specific impact on the role of injuries, whereas for women, both NCDs and injuries gain a more significant share with mortality decreases.

For children over one year, they find that there is a gradual transition from communicable to non-communicable diseases, with injuries remaining significant in males.

The picture is more nuanced in low- and middle-income countries, where there are signs of a protracted transition with the double burden of communicable and noncommunicable disease.

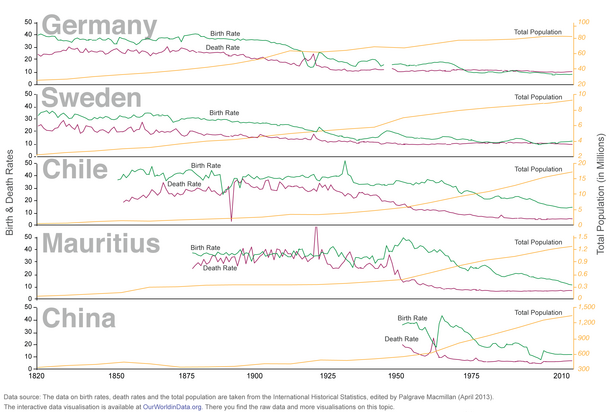

Pink line: crude death rate (CDR), green line: (crude) birth rate (CBR), yellow line: population.