Equal Protection Clause

[6] Black people were considered inferior to white Americans, and subject to chattel slavery in the slave states until the Emancipation Proclamation and the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.

[6] In the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, the Supreme Court rejected abolitionism and determined black men, whether free or in bondage, had no legal rights under the U.S. Constitution at the time.

"[10] President Andrew Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 amid concerns (among other things) that Congress did not have the constitutional authority to enact such a bill.

[21] The scope of this clause was substantially narrowed following the Slaughterhouse Cases in which it was determined that a citizen's privileges and immunities were only ensured at the Federal level and that it was government overreach to impose this standard on the states.

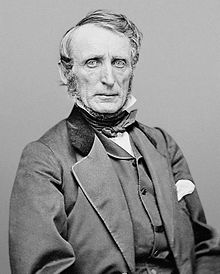

Here is the first version: "The Congress shall have power to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper to secure ... to all persons in the several states equal protection in the rights of life, liberty, and property.

"[23] Bingham said about this version: "It confers upon Congress power to see to it that the protection given by the laws of the States shall be equal in respect to life and liberty and property to all persons.

[30] In 1872, the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that the state's ban on mixed-race marriage violated the "cardinal principle" of the 1866 Civil Rights Act and of the Equal Protection Clause.

Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented alone, saying, "I cannot resist the conclusion that the substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the Constitution have been sacrificed by a subtle and ingenious verbal criticism."

[40] In it the word "person" from the Fourteenth Amendment's section has been given the broadest possible meaning by the U.S. Supreme Court:[41] These provisions are universal in their application to all persons within the territorial jurisdiction, without regard to any differences of race, of color, or of nationality, and the equal protection of the laws is a pledge of the protection of equal laws.Thus, the clause would not be limited to discrimination against African Americans, but would extend to other races, colors, and nationalities such as (in this case) legal aliens in the United States who are Chinese citizens.

In its most contentious Gilded Age interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court upheld a Louisiana Jim Crow law that required the segregation of blacks and whites on railroads and mandated separate railway cars for members of the two races.

[44] Granting rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to business corporations was introduced into Supreme Court jurisprudence through a series of sleights of hands.

A second fraud occurred a few years later in the case of Santa Clara v. Southern Pacific Railroad, which left a written legacy of corporate rights under the Fourteenth Amendment.

[47][48] Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field seized on this deceptive and incorrect published summary by the court reporter Davis in Santa Clara v. Southern Pacific Railroad and cited that case as precedent in the 1889 case Minneapolis & St. Louis Railway Company v. Beckwith in support of the proposition that corporations are entitled to equal protection of the law within the meaning of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court, applying the separate-but-equal principle of Plessy, held that a State offering a legal education to whites but not to blacks violated the Equal Protection Clause.

The Shelley case concerned a privately made contract that prohibited "people of the Negro or Mongolian race" from living on a particular piece of land.

In Sweatt, the Court considered the constitutionality of Texas's state system of law schools, which educated blacks and whites at separate institutions.

Both men were extraordinarily skilled appellate advocates, but part of their shrewdness lay in their careful choice of which cases to litigate, selecting the best legal proving grounds for their cause.

Partly because of that enigmatic phrase, but mostly because of self-declared "massive resistance" in the South to the desegregation decision, integration did not begin in any significant way until the mid-1960s and then only to a small degree.

In response to Green, many Southern districts replaced freedom-of-choice with geographically based schooling plans; because residential segregation was widespread, little integration was accomplished.

[58] The curtailment of busing in Milliken v. Bradley is one of several reasons that have been cited to explain why equalized educational opportunity in the United States has fallen short of completion.

This modern doctrine was pioneered in Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942), which involved depriving certain criminals of the fundamental right to procreate:[71] When the law lays an unequal hand on those who have committed intrinsically the same quality of offense and sterilizes one and not the other, it has made as invidious a discrimination as if it had selected a particular race or nationality for oppressive treatment.Until 1976, the Supreme Court usually ended up dealing with discrimination by using one of two possible levels of scrutiny: what has come to be called "strict scrutiny" (when a suspect class or fundamental right is involved), or instead the more lenient "rational basis review".

[74] The whole tiered strategy developed by the Court is meant to reconcile the principle of equal protection with the reality that most laws necessarily discriminate in some way.

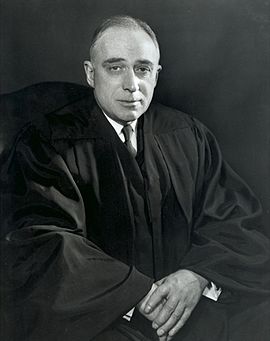

Justice Lewis Powell, writing for the Court, stated, "Proof of racially discriminatory intent or purpose is required to show a violation of the Equal Protection Clause."

[81] The Court found that the defense had failed to prove that such data demonstrated the requisite discriminatory intent by the Georgia legislature and executive branch.

It was not this holding that proved especially controversial among commentators, and indeed, the proposition gained seven out of nine votes; Justices Souter and Breyer joined the majority of five—but only for the finding that there was an Equal Protection violation.

[86] On the other hand, as feminists like Victoria Woodhull pointed out, the word "person" in the Equal Protection Clause was apparently chosen deliberately, instead of a masculine term that could have easily been used instead.

Notably, O'Connor's opinion did not claim to apply a higher level of scrutiny than mere rational basis, and the Court has not extended suspect-class status to sexual orientation.

Several important affirmative action cases to reach the Supreme Court have concerned government contractors—for instance, Adarand Constructors v. Peña (1995) and City of Richmond v. J.A.

In Bakke, the Court held that racial quotas are unconstitutional, but that educational institutions could legally use race as one of many factors to consider in their admissions process.

Although the scope and reach of these opinions are unknown, it is not uncommon for Supreme Court cases' rationale to be applied to similar or analogous facts or circumstances.