Equation of time

Apparent solar time can be obtained by measurement of the current position (hour angle) of the Sun, as indicated (with limited accuracy) by a sundial.

[1] The equation of time is the east or west component of the analemma, a curve representing the angular offset of the Sun from its mean position on the celestial sphere as viewed from Earth.

The equation of time values for each day of the year, compiled by astronomical observatories, were widely listed in almanacs and ephemerides.

The planet Uranus, which has an extremely large axial tilt, has an equation of time that makes its days start and finish several hours earlier or later depending on where it is in its orbit.

The lower graph (which covers exactly one calendar year) has the same absolute values but the sign is reversed as it shows how far the clock is ahead of the sun.

[citation needed] Book III of Ptolemy's Almagest (2nd century) is primarily concerned with the Sun's anomaly, and he tabulated the equation of time in his Handy Tables.

Based on Ptolemy's discussion in the Almagest, values for the equation of time (Arabic taʿdīl al-ayyām bi layālayhā) were standard for the tables (zij) in the works of medieval Islamic astronomy.

[14]: 57–58 The more accurate methods were also precursors to finding the observer's longitude in relation to a prime meridian, such as in geodesy on land and celestial navigation on the sea.

[16] The equation of time, correctly based on the two major components of the Sun's irregularity of apparent motion, was not generally adopted until after Flamsteed's tables of 1672–73, published with the posthumous edition of the works of Jeremiah Horrocks.

But the orbit of the Earth is an ellipse not centered on the Sun, and its speed varies between 30.287 and 29.291 km/s, according to Kepler's laws of planetary motion, and its angular speed also varies, and thus the Sun appears to move faster (relative to the background stars) at perihelion (currently around 3 January) and slower at aphelion a half year later.

Consequently, the smaller daily differences on other days in speed are cumulative until these points, reflecting how the planet accelerates and decelerates compared to the mean.

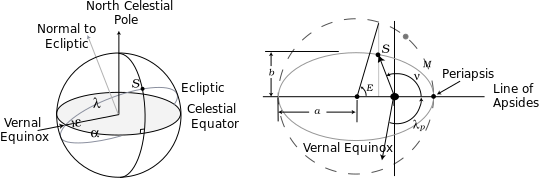

In terms of the equation of time, the inclination of the ecliptic results in the contribution of a sine wave variation with: This component of the EoT is represented by the aforementioned factor "b":

But it can be ignored in the current discussion as our Gregorian calendar is constructed in such a way as to keep the vernal equinox date at 20 March (at least at sufficient accuracy for our aim here).

In 1246 the perihelion occurred on 22 December, the day of the solstice, so the two contributing waves had common zero points and the equation of time curve was symmetrical: in Astronomical Algorithms Meeus gives February and November extrema of 15 m 39 s and May and July ones of 4 m 58 s. Before then the February minimum was larger than the November maximum, and the May maximum larger than the July minimum.

The secular change is evident when one compares a current graph of the equation of time (see below) with one from 2000 years ago, e.g., one constructed from the data of Ptolemy.

[25] If the gnomon (the shadow-casting object) is not an edge but a point (e.g., a hole in a plate), the shadow (or spot of light) will trace out a curve during the course of a day.

If the shadow is cast on a plane surface, this curve will be a conic section (usually a hyperbola), since the circle of the Sun's motion together with the gnomon point define a cone.

A convenient compromise is to draw the line for the "mean time" and add a curve showing the exact position of the shadow points at noon during the course of the year.

By comparing the analemma to the mean noon line, the amount of correction to be applied generally on that day can be determined.

The former are based on numerical integration of the differential equations of motion, including all significant gravitational and relativistic effects.

The following discussion describes a reasonably accurate (agreeing with almanac data to within 3 seconds over a wide range of years) algorithm for the equation of time that is well known to astronomers.

They can both be removed by subtracting 24 hours from the value of EOT in the small time interval after the discontinuity in α and before the one in αM.

The right ascension, and hence the equation of time, can be calculated from Newton's two-body theory of celestial motion, in which the bodies (Earth and Sun) describe elliptical orbits about their common mass center.

At the specific value E = π for which the argument of tan is infinite, use ν = E. Here arctan x is the principal branch, |arctan x| < π/2; the function that is returned by calculators and computer applications.

As a practical matter this means that one cannot get a highly accurate result for the equation of time by using n and adding the actual periapsis date for a given year.

However, high accuracy can be achieved by using the formulation in terms of D. When D > Dp, M is greater than 2π and one must subtract a multiple of 2π (that depends on the year) from it to bring it into the range 0 to 2π.

The plot of Δtey is seen to be close to the results produced by MICA, the absolute error, Err = |Δtey − MICA2000|, is less than 1 minute throughout the year; its largest value is 43.2 seconds and occurs on day 276 (3 October).

However, in order to achieve this level of accuracy over this range of years it is necessary to account for the secular change in the orbital parameters with time.

In all this note that Δtey as written above is easy to evaluate, even with a calculator, is accurate enough (better than 1 minute over the 80-year range) for correcting sundials, and has the nice physical explanation as the sum of two terms, one due to obliquity and the other to eccentricity that was used previously in the article.

The excess half-turns are removed in the next step of the calculation to give the equation of time: The expression nint(C) means the nearest integer to C. On a computer, it can be programmed, for example, as INT(C + 0.5).