List of Assyrian kings

Ancient Assyrian history is typically divided into the Old, Middle and Neo-Assyrian periods, all marked by ages of ascendancy and decline.

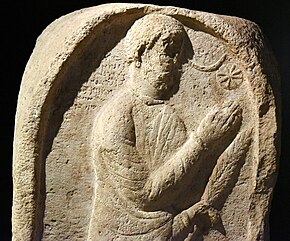

The ancient Assyrians did not believe that their king was divine himself, but saw their ruler as the vicar of their principal deity, Ashur, and as his chief representative on Earth.

At times, Assur and other Assyrian cities were afforded great deals of autonomy by its foreign rulers after the 7th century BC, particularly under the Achaemenid and Parthian empires.

[3] The king-lists mostly accord well with Hittite, Babylonian and ancient Egyptian king lists and with the archaeological record, and are generally considered reliable for the age.

In times of civil strife and confusion, the list still adheres to a single royal line of descent, probably ignoring rival claimants to the throne.

[9] Assyrian royal titles typically followed trends that had begun under the Akkadian Empire (c. 2334–2154 BC), the Mesopotamian civilization that preceded the later kingdoms of Assyria and Babylon.

Some cases display lineage stretching back much further, Shamash-shum-ukin (r. 667–648 BC) describes himself as a "descendant of Sargon II", his great-grandfather.

More extremely, Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC) calls himself a "descendant of the eternal seed of Bel-bani", a king who lived more than a thousand years before him.

[15] Epithets like "chosen by the god Marduk and the goddess Sarpanit" and "favourite of the god Ashur and the goddess Mullissu", both assumed by Esarhaddon, illustrate that he was both Assyrian (Ashur and Mullissu, the main pair of Assyrian deities) and a legitimate ruler over Babylon (Marduk and Sarpanit, the main pair of Babylonian deities).

To aid the king with this duty, there was a number of priests at the royal court trained in reading and interpreting signs from the gods.

[18] The heartland of the Assyrian realm, Assyria itself, was thought to represent a serene and perfect place of order whilst the lands governed by foreign powers were perceived as infested with disorder and chaos.

[19] Because the king was the earthly link to the gods, it was his duty to spread order throughout the world through the military conquest of these strange and chaotic countries.

A text from the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. c. 1243–1207 BC) states that the king received a royal scepter and was commanded to "broaden the land of Ashur".

To the Assyrians, the most dangerous animal of all was the lion, used (similarly to foreign powers) as an example of chaos and disorder due to their aggressive nature.

To prove themselves worthy of rule and illustrate that they were competent protectors, Assyrian kings engaged in ritual lion hunts.

[3] Given that the earliest rulers are described as "kings who lived in tents", they, if real, may not have ruled Assur at all but rather have been nomadic tribal chieftains somewhere in its vicinity.

Including these figures may have served to justify Shamshi-Adad's rise to the throne, either through obscuring his non-Assyrian origins or through inserting his ancestors into the sequence of Assyrian kings.

[41][42] During the rule of Shamshi-Adad I and his successors, of Amorite descent and originally from the south, a more absolute form of kingship, inspired by that of Babylon, was introduced in Assyria.

[25] Shamshi-Adad I was also the first Assyrian king to assume the title 'king of the Universe',[44] though these styles fell into a long period of disuse again after his death.

[117] A semi-autonomous city-state under Parthian suzerainty appears to have formed around the city of Assur,[w] Assyria's oldest capital,[120] near, or shortly after, the end of the 2nd century BC.

[122] The ancient temple dedicated to the god Ashur was also restored for the second time in the second century AD, and a cultic calendar effectively identical to that used under the Neo-Assyrian Empire was used.

[124] This second period of prominent Assyrian cultural development at Assur came to end with the conquests of the Sasanian Empire in the region, c. 240,[118] whereafter the Ashur temple was destroyed again and the city's people were dispersed.