Ernst Laas

[1] During this time as a young boy, Ernst and his younger brother had to collect firewood from the heath in his area after school each day to help their parents, who struggled just to provide the most basic food through their hard work.

Upon leaving school, Ernst noted that his personal struggles and experiences, combined with the educational methods used at home, led him to develop a shy and reserved demeanor which others found off-putting.

Under Trendelenburg's guidance, Laas' philosophical thinking initially oriented around Aristotle, and in his doctoral dissertation, he adopted a similar method to what Lessing later successfully employed.

The more firmly he grounded himself in this new scientific reality, the more rigorously he analyzed phenomena and immersed himself in their development, and the more he distanced himself from theories that twist away from the facts or try to leap to a “higher” understanding through some intellectual gymnastics.

It was as if he saw his calling to wrestle on our behalf with all the riddles that can torment the human mind and heart, to confront the demons that haunt our spiritual existence, so that we could find joy and delicately share in all things human—a sacrifice he made for his mission that was not due to any inherent harshness in his nature.

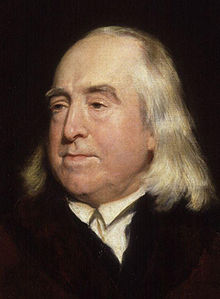

Laas, for example, asserted – similar to Hume, Mill, and Spencer, as well as in contrast to proponents of Kantian philosophy – that human reason is not capable of producing ideas and concepts that guarantee the objectivity of our knowledge and moral actions.

Laas highlights this nationalism at the end of the final volume of Idealism and Positivism: As sad as it is, it is a fact that nowadays within certain circles one can already prejudice against a doctrine by simply describing it as an import from England or France: it appears both as unoriginal and unpatriotic.

And this contentious history can be traced to Wilhelm Windelband's influential 1884 characterization, where he dismissed relativism as "the philosophy of the jaded person who no longer believes in anything," and thus associating it specifically with urban skepticism and intellectual inconsistency.

From both the political and scientific standpoint, it appears advisable not to leave the field exclusively to the latter school at the university, but rather to restore the proven counterweight, which found its support in the person and teaching of Prof. Liebmann, after his departure through a similar force.

[15]The university brought in Windelband to succeed Liebmann, specifically to prevent the establishment of a Laasian school of thought and block it from gaining a foothold in Strasbourg for political and moral reasons.

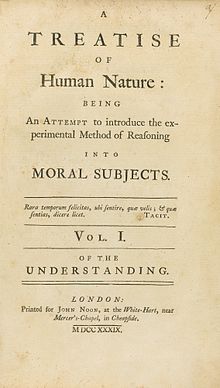

[16] In the conclusion of the third volume of his trilogy, Laas wrote about the philosophical and political significance of his investigations:When I placed my philosophical convictions in fundamental opposition to such highly celebrated names as Plato and Kant; when I seemed to declare war on the idealism praised by countless voices; when I set my views in historical connection with the infinitely often pilloried aphorisms of one of the despised Athenian sophists; when I revealed a certain predilection for the almost frivolous skeptic David Hume; when I introduced my own doctrine under the title of positivism: I had to be prepared for all sorts of misunderstandings and dialectical fencing tricks in an age where slogans often have more effect than arguments, where all forms of “intrusions into another field” (μετάβασις εἰς ἄλλο γένος) flourish most luxuriantly which tendentious rhetoric has invented, where one has become accustomed to defending occupied territory with all means of self-love and sophistry.

On the contrary, he considered some life and world views currently represented in the name of idealistic philosophy not just inaccurate but even “dangerous,” indeed “culturally dangerous.”[17]However as much as I hold certain forms of “idealism” in high regard, I cannot regret having marked the contrast more than my kinship from the outset.

So I hope that this may, in fact, contribute to a purer, more adequate knowledge of the matter represented here, even if it not only renounced rhetorical support but even seemed hostile to the idol of national bias.But due to overwork, he suffered from health issues as early as 1877.

According to him, it was free from the “arbitrary absolutisms of speculative philosophy,” especially that of Hegel – as P. Jacob Kohn states in his dissertation on Laas's positivism – and it employed the method of sciences practiced at the time.

Just as Trendelenburg attempted[30] by distinguishing between the “fundamental” aspects of a philosophy and its “derived” elements, so that "we might yet recognize the inherent organization, structure, and necessity within this diversity,"[26] for: The rich array of nuances, shades, entanglements, and complications, along with the many inconsistencies of the authors, have made it possible to weave a fabric with just two threads and two basic colors that initially gives the impression of dazzling variety.

But in contrast to the a priori, idealists only assigned a subordinate role to sensory “perceptions,” “sensations” and “facts.”[36][37] At first look, Laas observed it might seem as if the “transcendental philosophical turn… is vastly different from the Platonic view.” However, upon closer inspection, an “interesting kinship” emerges.

“Besides instances where Plato appropriately and clearly distinguishes the positions of the young Theaetetus, the sophist Protagoras, and the ‘Ionians,’ there are other places where the opposition is described in such a general and vague manner that it's hard to definitively say who or what is being discussed.

The worst part is that relativism and Heraclitism are so interwoven – often transitioning into each other – that the shifting expression, like a reflection of the presumed indeterminate being, allows no definite interpretation, nor even a clear emphasis of the words.

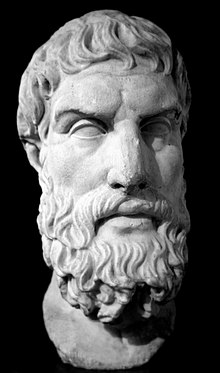

And so Laas thinks that this Platonic dialogue, which is solely focused on experiential epistemology and at the same time tries to prove it false, gives the original roots of the principals which he counts as the basis for his positivist philosophy in its earliest and strongest form.

“While the sensualism described by Plato (and Aristotle) may still be underdeveloped and lacking in detail, some of its most characteristic features are already so clearly defined that the subsequent work on this principle – since the revival of Epicureanism by Gassendi, especially by the English nominalists and empiricists – has hardly shown any significant deviations in its core essence.

Thus, his idealistic critique and response remain significant up to the present day.”[48] Laas attempts to give a reconstruction of Plato's argument of Protagoras’ sensualism in order to show how the underlying principles originated for his own philosophy.

For this reason, Laas tried to point out a tendency within Platonism: it drifts towards non-scientific realms of myths and pious intuitions, while simultaneously blurring the lines between serious philosophical inquiry and mere images.

As a result, Kant sought to redefine the boundaries of “pure reason,” thereby limiting its domain to the field of possible experience and establishing a priori knowledge as foundational to human cognition.

As Hume had made clear, it is questionable to construct causal connections and habitually hold them to be “true.”[62] From an idealistic perspective, it is objected that the sensibly experienceable does not serve as a suitable basis for investigation because it continuously changes.

Likewise for Laas, correlativism distinctly rejects the notions of subjectivism and idealism that were put forward by philosophers like Descartes, Berkeley, and Kant, where they argued against this idea that perceptions are merely subjective experiences or modifications of consciousness.

According to Laas, modern idealistic epistemology, whose main proponent Kant with his transcendental philosophical version of rational idealism that starts from something secondary, namely a genetically later element, is “reason,” and declares it the spiritual “court of justice” [Gerichtshof] that evaluates all knowing.

[105] Accordingly, in the first preface of the Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787), he devalued the “physiology of the human mind” conducted by Locke in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) because Locke had derived it from the “rabble of common experience.”[106] In 1877, a reviewer of the Jena Literary Gazette[107] recommended to the Kantian adherents of the a priori of his time to confront this “vigorous attack on the transcendental hypothesis.” It might be, the reviewer suggested, that Laas's critique marks a “turning point in the development of the theory of knowledge, that is currently being worked on so much.”[108] The prevailing theory of knowing seems to have “perceived” this possible “turning point” as a “blind spot” of its own knowledge.

This applies to all views that assume human innate nature enables people to make morally correct decisions and act accordingly, as was the case for Aristotle and philosophers who followed him.

He noted that these institutions still clung to the centuries-old, scholastic form of education which believed it could do without any connection to real life and instead practiced the exclusive imparting of theoretical book style knowledge.

And so from that point on, the historical progression from Hume to Kant now seemed justifiable to me.” In the end, despite the rigorous mentorship, differences in philosophical outlook eventually led to the cessation of a long-standing collaboration with the fellow philosopher, described by Laas in a letter to Natorp as a divergence of “natural destiny.” “Everyone follows the path dictated by their original intellectual constitution; it's good to try for a long time to understand and benefit from even contrary thoughts; and you have followed this path with self-denying perseverance for a long time, but I believe it is now better for you to continue developing along the proper course of your natural destiny.”[1] Laas then pointed Natorp towards the Kantians from whom he believed he would gain more support than from him.