Jeremy Bentham

in Houndsditch, London,[1] to attorney Jeremiah Bentham and Alicia Woodward, widow of a Mr Whitehorne and daughter of mercer Thomas Grove, of Andover.

He was reportedly a child prodigy: he was found as a toddler sitting at his father's desk reading a multi-volume history of England, and he began to study Latin at the age of three.

[24] His 130-page tract was distributed in the colonies and contained an essay titled "Short Review of the Declaration" written by Bentham, a friend of Lind, which attacked and mocked the Americans' political philosophy.

[25][26] In 1786 and 1787, Bentham travelled to Krichev in White Russia (modern Belarus) to visit his brother, Samuel, who was engaged in managing various industrial and other projects for Prince Potemkin.

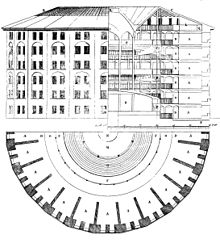

It was Samuel (as Jeremy later repeatedly acknowledged) who conceived the basic idea of a circular building at the hub of a larger compound as a means of allowing a small number of managers to oversee the activities of a large and unskilled workforce.

[32] But Bentham spent some sixteen years of his life developing and refining his ideas for the building and hoped that the government would adopt the plan for a National Penitentiary appointing him as contractor-governor.

After unsuccessful attempts to interest the authorities in Ireland and revolutionary France,[36] he started trying to persuade the prime minister, William Pitt, to revive an earlier abandoned scheme for a National Penitentiary in England, this time to be built as a panopticon.

3. c. 114) for the earlier penitentiary, at Battersea Rise; but the new proposals ran into technical legal problems and objections from the local landowner, Earl Spencer.

Although this was common land, with no landowner, there were a number of parties with interests in it, including Earl Grosvenor, who owned a house on an adjacent site and objected to the idea of a prison overlooking it.

Again, therefore, the scheme ground to a halt[40] At this point, however, it became clear that a nearby site at Millbank, adjoining the Thames, was available for sale, and this time things ran more smoothly.

When he asked the government for more land and more money, however, the response was that he should build only a small-scale experimental prison—which he interpreted as meaning that there was little real commitment to the concept of the panopticon as a cornerstone of penal reform.

However, as it became clear that there was still no real commitment to the proposal, he abandoned hope, and instead turned his attentions to extracting financial compensation for his years of fruitless effort.

[50][51] In 1821, John Cartwright proposed to Bentham that they serve as "Guardians of Constitutional Reform", seven "wise men" whose reports and observations would "concern the entire Democracy or Commons of the United Kingdom".

[53] In 1823, he co-founded The Westminster Review with James Mill as a journal for the "Philosophical Radicals"—a group of younger disciples through whom Bentham exerted considerable influence in British public life.

Hopeful to the last, at the age of eighty he wrote again to one of them, recalling to her memory the far-off days when she had "presented him, in ceremony, with the flower in the green lane" [citing Bentham's memoirs].

To the end of his life he could not hear of Bowood without tears swimming in his eyes, and he was forced to exclaim, "Take me forward, I entreat you, to the future—do not let me go back to the past.

He was also aware of the relevance of forced saving, propensity to consume, the saving-investment relationship, and other matters that form the content of modern income and employment analysis.

In his unique way, Bentham defined and analyzed the England of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, creating not only a comprehensive social theory but, with the help of James Mill and others, a political movement to go with it .

The essay chastises the society of the time for making a disproportionate response to what Bentham appears to consider a largely private offence—public displays or forced acts being dealt with rightly by other laws.

[77] However, his writings on the subject laid the foundation for the moderately successful codification work of David Dudley Field II in the United States a generation later.

This he describes by picturing the world as a gymnasium in which each "gesture, every turn of limb or feature, in those whose motions have a visible impact on the general happiness, will be noticed and marked down".

This circumstance, as far as it is distinct from climate, rank, and education, and from the two just mentioned, operates chiefly through the medium of moral, religious, sympathetic, and antipathetic biases".Bentham today is considered as the "Father of Utilitarianism".

He wrote in An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation:[86] Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure.

[citation needed] In his exposition of the felicific calculus, Bentham proposed a classification of 12 pains and 14 pleasures, by which we might test the "happiness factor" of any action.

[88] For Bentham, according to P. J. Kelly, the law "provides the basic framework of social interaction by delimiting spheres of personal inviolability within which individuals can form and pursue their own conceptions of well-being".

From 1833, it stood in Southwood Smith's Finsbury Square consulting rooms until he abandoned private practice in the winter of 1849–50, when it was moved to 36 Percy Street, the studio of his unofficial partner, painter Margaret Gillies, who made studies of it.

A large painting by Henry Tonks hanging in UCL's Flaxman Gallery depicts Bentham approving the plans of the new university, but it was executed in 1922 and the scene is entirely imaginary.

Several of his works first appeared in French translation, prepared for the press by Étienne Dumont, for example, Theory of Legislation, Volume 2 (Principles of the Penal Code) 1840, Weeks, Jordan, & Company.

[119] John Bowring, the young radical writer who had been Bentham's intimate friend and disciple, was appointed his literary executor and charged with the task of preparing a collected edition of his works.

The project was launched in September 2010 and is making freely available, via a specially designed transcription interface, digital images of UCL's vast Bentham Papers collection—which runs to some 60,000 manuscript folios—to engage the public and recruit volunteers to help transcribe the material.