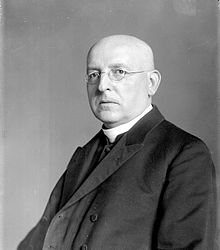

Ernst Streeruwitz

A member of the industrialist wing of the Christian Social Party, Streeruwitz served on the National Council from November 1923 to October 1930 and as chancellor and foreign minister from May to September 1929.

[1] The child was the youngest son of Georg Adolf von Streeruwitz, a member of the Imperial Council and the city's hereditary postmaster.

The Streeruwitz family, originally from Friesland, had migrated to Bohemia during the Thirty Years' War and been ennobled for outstanding bravery during the Battle of Prague.

Ever since, the family had been fiercely loyal to the Austrian Empire and provided officers for the army and career civil servants for the Mies municipal and regional administrations.

Ernst Streeruwitz's childhood was colored by the dissonance between the family's ancient loyalty to the House of Habsburg and its newfound pan-Germanism.

[2] The two positions had become difficult to reconcile after Austria's defeat in the Battle of Königgrätz forced the Habsburgs to clamp down on civic nationalism as a matter of political survival.

The boy, who was already bilingual in German and Czech, his mother was an ethnically-Czech daughter of the city bourgeoisie, was taught French from an early age and generally received a thorough education.

His mother saw no hope of getting the son admitted into the diplomatic service without the late patriarch's political connections and so persuaded Streeruwitz to join the army instead.

Starting in 1895, he served as a lieutenant with the 7th Bohemian Dragoons (Duke of Lorraine's), stationed in Lissa an der Elbe at the time.

Streeruwitz received excellent evaluations from his superior officers and was encouraged to sit the entrance exam for the War College, graduating from which would have all but guaranteed a stellar career.

Streeruwitz lost his faith in his ability to withstand the rigors of military life and applied to be granted reservist status.

[4] While waiting to be allowed to leave active service, Streeruwitz began studying mechanical engineering at the College of Technology and law at the University of Vienna.

He nevertheless moved to Vienna a third time when it became clear that the Republic of Austria would not be able to press home its claim to the majority-German parts of Bohemia.

In terms of policy, Streeruwitz believed that the answer to Austria's economic troubles was increased productivity; that belief led him to oppose social measures such as working time reductions and to advocate for a hard line against strikers.

[12] During the runup to the 1923 legislative elections, the Federation of Austrian Industries and the Christian Social Party negotiated an agreement of mutual support.

Whereas Austrian independence had gradually become one of the Christian Social Party's defining platform planks, Streeruwitz continued to support the integration of Austria into the German Reich.

Catholic clericalism was another one of the party's defining platform planks, but Streeruwitz, like most Austrian pan-Germans and like his father before him, was hostile to political Catholicism.

Even though he vocally despised leading Social Democrats such as Otto Bauer and Robert Danneberg, and the Arbeiter-Zeitung reciprocated with a string of personal attacks, Streeruwitz thought highly of Karl Renner and was ready to work with the opposing side if common ground could be found.

He helped draft a number of significant statutes and published numerous opinion pieces arguing his policy positions.

The glut endangered Austria's struggling manufacturing sector, but the country was largely defenseless because of a number of free trade agreements that the empire's successor states had hastily concluded immediately after its collapse.

[20][21][22][23] The growing Austrofascist Heimwehr movement demanded a move to a presidential system with a strong leader, modelled on Benito Mussolini's Fascist Italy and Miklós Horthy's Regency Hungary.

The sixth-largest city in the world and the capital of a global power for five centuries, Vienna was a bustling cosmopolitan metropolis, even in times of economic hardship.

Seipel, nicknamed the "prelate without mercy" ("Prälat ohne Milde") by friends and foes alike, was a hardline clericalist whose very personality would be an obstacle.

[33] Streeruwitz's inaugural address on 7 May mainly dealt with economic and foreign policy but also included a firm commitment to representative democracy.

On 18 August, however, a bloody street fight in Sankt Lorenzen im Mürztal, Styria, brought the belligerence to the surface again and heightened it to unprecedented levels.

Even though he had been warned that the Sankt Lorenzen police would not have the numbers to keep the two factions apart, Governor Rintelen refused to prohibit the rallies or to arrange for the army to send assistance.

When Streeruwitz left Austria to represent the country at the Tenth General Assembly of the League of Nations, his opponents used his absence to co-ordinate his overthrow and to agree on a successor.

Faced with vicious attacks from all sides, impossible demands and a threat on the part of the Landbund to leave the coalition, Streeruwitz resigned, effective 26 September.

The Christian Social party and later the Fatherland Front occasionally hinted that Streeruwitz was being considered for a political comeback but ultimately removed him even from his position as the chairman of the chamber.