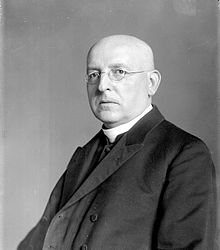

Johannes Schober

He also served ten stints as an acting minister, variously leading the ministries of education, finance, commerce, foreign affairs, justice, and the interior, sometimes just for a few days or weeks at a time.

Schober remained the only chancellor in Austrian history with no official ideological affiliation until 2019, when Brigitte Bierlein was appointed, becoming the first woman to take office.

[7][8] During the chaos days of the collapse of the Empire in late 1918, Schober's tact and resourcefulness played a crucial role in maintaining peace and public order in Vienna.

[9] Following the proclamation of the Republic of German-Austria on 12 November, Schober placed his forces at the disposal of the provisional government but also secured the safety of the Imperial Family, whose departure from Vienna he supervised.

[13] In March, however, Béla Kun's establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic encouraged parts of the Communist leadership to try to seize power by force.

[15][16] The Communists began preparing a mass protest for 15 June, urging their supporters to carry arms and hoping to turn the march into an insurrection.

"[20] The fourteen parties in Austria's Constituent Assembly had radically different visions regarding the constitutional, territorial, and economic future of their demoralized, impoverished rump state.

Austrians began to warm to the idea of a "cabinet of civil servants" ("Beamtenkabinett"), a government of senior career bureaucrats who would be loyal to the State and not to any particular ideological camp.

A pool of highly educated middle-aged administrators who counted sober professionalism as an important aspect of their self-image stood ready to be tapped.

[22] Ignaz Seipel, chairman of the Christian Social Party, was reluctant to assume the chancellorship because of the difficult decisions and general hardship he knew still lay ahead; he wanted someone else to do the dirty work.

The Republic of German-Austria had been proclaimed with the understanding that it would eventually join the German Reich, a vision shared by a clear majority of its population at the time.

In addition to holding the chair, Schober led the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, although only in an acting capacity (mit der Leitung betraut) and not as an actual minister.

[29][34] Schober's resignation ended the coalition and therefore relieved the People's Party of its contractual obligation to side with the cabinet in the National Council, i.e. to support the ratification of the Treaty of Lana.

Having been able to vote in opposition, the People's Party was partially appeased and was ready to resume support for the Schober government, who in any case was still the only plausible contender.

While Schober continued to fight Austria's crippling financial problems and otherwise focused on foreign policy, Seipel, still the chairman of the Christian Social Party, decided that the time had come for him to take over.

[40] On 30 January 1927 members of the Frontkämpfer militia opened fire on an unarmed and unsuspecting crowd of Social Democrats in an ambush attack in the small town of Schattendorf, killing two and wounding five others.

Their stated aims were "uniting all Aryan front-line fighters" ("Vereinigung aller arischen Frontkämpfer"), "nurturing the love for the homeland" ("Pflege der Liebe zur Heimat"), fighting leftists, and suppressing Jews.

Fearing for the lives of those trapped inside the Palace, police decided to disperse the mob by shooting their rifles – mainly into the air, but also into the crowd.

[51] Schober, who sincerely believed that he had always treated the Social Democrats with fairness and whose skin was thinner than his reputation suggested, experienced the attacks as vicious and appears to have been genuinely hurt.

[52] In spite of the successful integration of Austria into the international community that Schober – and later Seipel – achieved, the country's economic situation continued to deteriorate.

A system of thought developed that combined Fascism, Catholic clericalism, and the Antisemitism traditionally endemic in large parts of the Austrian political right.

On the one hand, he signalled willingness to meet Heimwehr demands for constitutional reform halfway, continuing negotiations where the Streeruwitz government had left off.

Schober invited Social Democratic representatives to join the talks and refused to be intimidated by the rallies the Heimwehr kept staging as a show of force.

Short, pudgy, intellectually outmatched, eager to oblige, happy to be patronized, and head of a country that was no threat to anyone any more, Schober seems to have put his negotiating partners into a generous mood.

According to one contemporary Austrian cartoon, Schober received so many friendly pats on the shoulder from foreign dignitaries that he took to traveling with a cushion strapped to his back.

[77] Dissatisfied by the new constitution and in financial straits due to a crisis in the Austrian banking sector that had toppled one of its main donors, the Heimwehr decided that the way forward was to increase the pressure again.

[83] Lacking support from either of the Christian Socials' traditional coalition partners – the nationalist Greater German People's Party and the agrarian Landbund – the Vaugoin government was stillborn.

Except for the fact that the Heimwehr won a meager eight seats, taking seven of them from the Christian Socials, the composition of the National Council remained virtually unchanged.

To prevent the total collapse of its economy, Austria now needed an immediate cash infusion in an amount that the struggling Reich was unable to muster.

[103] When his continued presence in the cabinet endangered the issuance of a strategic foreign currency bond, the Buresch government resorted to a sham resignation to remove Schober from office.