Carmen

The depictions of proletarian life, immorality, and lawlessness, and the tragic death of the main character on stage, broke new ground in French opera and were highly controversial.

At his death Bizet was still in the midst of revising his score and because of other later changes (notably the introduction of recitatives composed by Ernest Guiraud in place of the original dialogue) there is still no definitive edition of the opera.

[2][3] When artistic life in Paris resumed after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, Bizet found wider opportunities for the performance of his works; his one-act opera Djamileh opened at the Opéra-Comique in May 1872.

[5] The subject of the projected work was a matter of discussion between composer, librettists and the Opéra-Comique management; Adolphe de Leuven, on behalf of the theatre, made several suggestions that were politely rejected.

[8] Mérimée's story is a blend of travelogue and adventure yarn, possibly inspired by the writer's lengthy travels in Spain in 1830, and had originally been published in 1845 in the journal Revue des deux Mondes.

Invited inside, he introduces himself with the "Toreador Song" ("Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre") and sets his sights on Carmen, who brushes him aside.

When only Carmen, Frasquita and Mercédès remain, smugglers Dancaïre and Remendado arrive and reveal their plans to dispose of some recently acquired contraband ("Nous avons en tête une affaire").

In the original, events are spread over a much longer period of time, and much of the main story is narrated by José from his prison cell, as he awaits execution for Carmen's murder.

[31] Most of the characters in Carmen—the soldiers, the smugglers, the Gypsy women and the secondary leads Micaëla and Escamillo—are reasonably familiar types within the opéra comique tradition, although drawing them from proletarian life was unusual.

While each is presented quite differently from Mérimée's portrayals of a murderous brigand and a treacherous, amoral schemer,[23] even in their relatively sanitised forms neither corresponds to the norms of opéra comique.

[43] Jacques Bouhy, engaged to sing Escamillo, was a young Belgian-born baritone who had already appeared in demanding roles such as Méphistophélès in Gounod's Faust and as Mozart's Figaro.

[44] Marguerite Chapuy, who sang Micaëla, was at the beginning of a short career in which she was briefly a star at London's Theatre Royal, Drury Lane; the impresario James H. Mapleson thought her "one of the most charming vocalists it has been my pleasure to know".

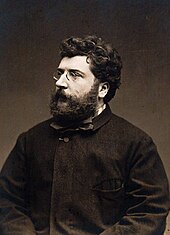

[46] The final rehearsals went well, and in a generally optimistic mood the first night was fixed for 3 March 1875, the day on which, coincidentally, Bizet's appointment as a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour was formally announced.

[48] The critic Ernest Newman wrote later that the sentimentalist Opéra-Comique audience was "shocked by the drastic realism of the action" and by the low standing and defective morality of most of the characters.

Among the few supportive critics was the poet Théodore de Banville; writing in Le National, he applauded Bizet for presenting a drama with real men and women instead of the usual Opéra-Comique "puppets".

[58] Among those who attended one of these later performances was Tchaikovsky, who wrote to his benefactor, Nadezhda von Meck: "Carmen is a masterpiece in every sense of the word ... one of those rare creations which expresses the efforts of a whole musical epoch.

The opera found particular favour in Germany, where the Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, apparently saw it on 27 different occasions and where Friedrich Nietzsche opined that he "became a better man when Bizet speaks to me".

Carvalho was roundly condemned by the critics for offering a travesty of what had come to be regarded as a masterpiece of French opera; nevertheless, this version was acclaimed by the public and played to full houses.

[73] Dean has commented on the dramatic distortions that arise from the suppression of the dialogue; the effect, he says, is that the action moves forward "in a series of jerks, rather instead of by smooth transition", and that most of the minor characters are substantially diminished.

Oeser reintroduces material removed by Bizet during the first rehearsals, and ignores many of the late changes and improvements that the composer made immediately before the first performance;[25] he thus, according to Susan McClary, "inadvertently preserves as definitive an early draft of the opera".

[81] While he places the opera firmly within the long opéra comique tradition,[82] Macdonald considers that it transcends the genre and that its immortality is assured by "the combination in abundance of striking melody, deft harmony and perfectly judged orchestration".

[19] Dean sees Bizet's principal achievement in the demonstration of the main actions of the opera in the music, rather than in the dialogue, writing that "Few artists have expressed so vividly the torments inflicted by sexual passions and jealousy."

Dean places Bizet's realism in a different category from the verismo of Puccini and others; he likens the composer to Mozart and Verdi in his ability to engage his audiences with the emotions and sufferings of his characters.

[84] He used a genuine folksong as the source of Carmen's defiant "Coupe-moi, brûle-moi" while other parts of the score, notably the "Seguidilla", utilise the rhythms and instrumentation associated with flamenco music.

After her provocative habanera, with its persistent insidious rhythm and changes of key, the fate motif sounds in full when Carmen throws her flower to José before departing.

[89] A muted reference to the fate motif on an English horn leads to José's "Flower Song", a flowing continuous melody that ends pianissimo on a sustained high B-flat.

[95] The long finale, in which José makes his last pleas to Carmen and is decisively rejected, is punctuated at critical moments by enthusiastic off-stage shouts from the bullfighting arena.

[105][106] In 1983 the stage director Peter Brook produced an adaptation of Bizet's opera known as La Tragedie de Carmen in collaboration with the writer Jean-Claude Carrière and the composer Marius Constant.

The films were made in various languages and interpreted by several cultures, and have been created by prominent directors including Gerolamo Lo Savio [it] (1909) [it], Raoul Walsh (1915) with Theda Bara,[108] Cecil B. DeMille (1915),[109] and The Loves of Carmen (1948) with Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford, directed by Charles Vidor.

Otto Preminger's 1954 Carmen Jones, with an all-black cast, is based on the 1943 Oscar Hammerstein Broadway musical of the same name, an adaptation of the opera transposed to 1940s North Carolina extending to Chicago.