Estado Novo (Portugal)

The Estado Novo, greatly inspired by conservative and autocratic ideologies, was developed by António de Oliveira Salazar, who was President of the Council of Ministers from 1932 until illness forced him out of office in 1968.

From 1950 until Salazar's death in 1970, Portugal saw its GDP per capita increase at an annual average rate of 5.7 per cent, leading to significant economic convergence with wealthier Western European nations.

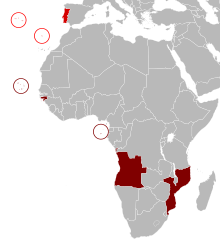

Its policy envisaged the perpetuation of Portugal as a pluricontinental empire, financially autonomous and politically independent from the dominating superpowers, and a source of civilization and stability to the overseas societies in the African and Asian possessions.

To support his colonial policies, Salazar eventually adopted Brazilian historian Gilberto Freyre's notion of lusotropicalism by asserting that, since Portugal had been a multicultural, multiracial, and pluricontinental nation since the 15th century, losing its overseas territories in Africa and Asia would dismember the country and end Portuguese independence.

[24] The parallel Corporative Chamber included representatives of municipalities, religious, cultural, and professional groups, and of the official workers' syndicates that replaced free trade unions.

Salazar denounced the National Syndicalists as "inspired by certain foreign models" and condemned their "exaltation of youth, the cult of force through direct action, the principle of the superiority of state political power in social life, [and] the propensity for organizing masses behind a single leader" as fundamental differences between fascism and the Catholic corporatism of the Estado Novo.

[43][44] Lisbon was the base for International Red Cross operations aiding Allied POWs and was the main air transit point between Britain and the U.S.[45] In 1942, Australian troops briefly occupied Portuguese Timor, but were soon overwhelmed by invading Japanese.

However, Lopes was not willing to give Salazar the free hand that Carmona had given him, and was forced to resign just before the end of his term in 1958.Naval Minister Américo Tomás, a staunch conservative, ran in the 1958 elections as the official candidate.

Evidence later surfaced that the PIDE had stuffed the ballot boxes with votes for Tomás, leading many neutral observers to conclude that Delgado would have won had Salazar allowed an honest election.

Anti-regime political activists were investigated and persecuted by PIDE-DGS (the secret police), and according to the gravity of the offence, were usually sent to jail or transferred from one university to another in order to destabilize oppositionist networks and their hierarchical organization.

[17] Other historians, like left-wing politician Fernando Rosas, point out that Salazar's policies from the 1930s to the 1950s, led to economic and social stagnation and rampant emigration, turning Portugal into one of the poorest countries in Europe, that was also thwarted by scoring lower on literacy than its peers of the Northern Hemisphere.

As it was thought that he did not have long to live, Tomás replaced him with Marcelo Caetano, former rector of the University of Lisbon and prominent scholar of its law school, and despite his protest resignation in 1962, a supporter of the regime.

With Portugal under the threat of an imminent financial collapse, Salazar finally agreed to become its 81st finance minister on 26 April 1928 after the republican and Freemason Óscar Carmona was elected president.

[64] Portuguese economic growth in the period 1960 to 1973 under the Estado Novo regime (and even with the effects of an expensive war effort in African territories against independentist guerrilla groups supported by the Communist Bloc and others), created an opportunity for real integration with the developed economies of Western Europe.

[citation needed] The very late and excruciatingly slow liberalization of the Portuguese economy gained a new impetus under Salazar's successor, Prime Minister Marcello José das Neves Caetano (1968–1974), whose administration abolished industrial licensing requirements for firms in most sectors and in 1972 signed a free trade agreement with the newly enlarged European Community.

Notwithstanding the concentration of the means of production in the hands of a small number of family-based financial-industrial groups, Portuguese business culture permitted a surprising upward mobility of university-educated individuals with middle-class backgrounds into professional management careers.

Before the 1974 Carnation Revolution, the largest, most technologically advanced (and most recently organized) firms offered the greatest opportunity for management careers based on merit rather than by accident of birth.

Brisa – Autoestradas de Portugal was founded in 1972 and the state granted the company a 30-year concession to design, build, manage, and maintain a modern network of express motorways.

Economically, the Estado Novo regime maintained a policy of corporatism that resulted in the placement of a big part of the Portuguese economy in the hands of a number of strong conglomerates, including those founded by the families of António Champalimaud (Banco Pinto & Sotto Mayor, Cimpor), José Manuel de Mello (CUF – Companhia União Fabril, Banco Totta & Açores), Américo Amorim (Corticeira Amorim) and the dos Santos family (Jerónimo Martins).

Other medium-sized family companies specialized in textiles (for instance those located in the city of Covilhã and the northwest), ceramics, porcelain, glass and crystal (like those of Alcobaça, Caldas da Rainha and Marinha Grande), engineered wood (like SONAE near Porto), motorcycle manufacturing (like Casal and FAMEL in the District of Aveiro), canned fish (like those of Algarve and the northwest which included one of the oldest canned fish companies in continuous operation in the world), fishing, food and beverages (alcoholic beverages, from liqueurs like Licor Beirão and Ginjinha, to beer like Sagres, were produced across the entire country, but port wine was one of its most reputed and exported alcoholic beverages), tourism (well established in Estoril, Cascais and Sintra (the Portuguese Riviera) and growing as an international attraction in the Algarve since the 1960s) and in agriculture and agribusiness (like the ones scattered around Ribatejo and Alentejo – known as the "breadbasket of Portugal", as well as the notorious Cachão Agroindustrial Complex[66] established in Mirandela, Northern Portugal, in 1963) completed the panorama of the national economy by the early 1970s and included export-orienteed foreign direct investment-funded businesses such as an automotive assembly plant founded in 1962 by Citroën which began operations in 1964 in Mangualde and a Leica factory established in 1973 in Vila Nova de Famalicão.

However, in a context of an expanding economy, bringing better living conditions for the Portuguese population in the 1960s, the outbreak of the colonial wars in Africa set off significant social changes, among them the rapid incorporation of more and more women into the labour market.

[74] The political constitution defines public education as aiming for: "in addition to the physical reinvigoration and the improvement of intellectual faculties, the formation of character, professional value and all civic and moral virtues" (Constituição de 1933, Artigo 43).

[78] The Mocidade Portuguesa was established in 1936, defined as a "national and pre-military organization that is able to stimulate the integral development of [the youth's] physical capacities, the formation of [their] character and devotion to the Fatherland and put [them] in conditions to be able to compete effectively for its defense" (Law 1941, Base XI).

[80] In 1965, an instructional television program was created (Telescola), filmed in Rádio e Televisão de Portugal's studios in Porto to support isolated rural areas and overcrowded suburban schools.

[89] In July 1973, after ample social discussion of his projects,[88] Veiga Simão launched a "Basic Law of Education",[90] which aimed to democratize education in Portugal[91] and, in August of that year, also launched a decree that would create the Nova de Lisboa, Aveiro and Minho universities, the Instituto Universitário de Évora, several politechnical schools (e.g., Covilhã, Faro, Leiria, Setúbal, Tomar, Vila Real) and superior schools (e.g., Beja, Bragança, Castelo Branco, Funchal, Ponta Delgada).

[94] In 1961, the Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá's annexation by the Republic of Dahomey was the start of a process that led to the final dissolution of the centuries-old Portuguese Empire.

[96] The various conflicts forced the Salazar and subsequent Caetano governments to spend more of the country's budget on colonial administration and military expenditures, and Portugal soon found itself increasingly isolated from the rest of the world.

The military-led coup can be described as the necessary means of bringing back democracy to Portugal, ending the unpopular Colonial War where thousands of Portuguese soldiers had been commissioned, and replacing the authoritarian Estado Novo (New State) regime and its secret police which repressed elemental civil liberties and political freedoms.

By refusing to grant independence to its overseas territories in Africa, the Portuguese ruling regime of Estado Novo was criticized by most of the international community, and its leaders Salazar and Caetano were accused of being blind to the "Winds of Change".

[citation needed] In the following decades, Portugal remained a net beneficiary of European Union Structural and Cohesion Funds and didn't avoid three IMF-led bailouts between the late 1970s and the early 2010s.