Marcelo Caetano

A conservative politician and a self-proclaimed reactionary in his youth,[2] Caetano started his political career in the 1930s, during the early days of the regime of António de Oliveira Salazar.

Caetano soon became an important figure in the Estado Novo government, and in 1940, he was appointed chief of the Portuguese Youth Organisation.

In jail for political reasons, Álvaro Cunhal, a law student, the future leader of the Portuguese Communist Party, submitted his final thesis on the topic of abortion before a faculty jury that included Caetano.

There were indeed three generations of militants of the radical right at the Portuguese universities and schools between 1945 and 1974 who were guided by a revolutionary nationalism partly influenced by the political subculture of European neofascism.

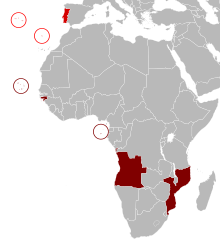

The core of these radical students' struggle lay in an uncompromising defence of the Portuguese Empire in the days of the fascist regime.

The three objectives of Caetano's pension reform were to enhance equity, reduce the fiscal and actuarial imbalance and achieve more efficiency for the economy as a whole such as by establishing contributions that were less distortive to labour markets and allowing the savings generated by pension funds to increase the investments in the economy.

Some large-scale investments were made at the national level, such as the building of a major oil processing center in Sines.

The economy reacted very well at first, but in the 1970s, some serious problems began to show, partly because double-digit inflation started 1970 and partly because of the short-term effects of the 1973 oil crisis despite the largely-unexploited oil reserves, which Portugal had in its overseas territories in Angola and São Tomé and Príncipe that were being developed and promised to become sources of wealth in the medium to long term.

The PIDE, the dreaded secret police, was renamed the DGS (Direcção-Geral de Segurança [pt], General-Directorate of Security).

The National Assembly [pt] was considered as not a chamber for parties but popular representatives, who were chosen and elected on a single list.

Throughout the war, Portugal also faced increasing dissent, arms embargoes and other punitive sanctions imposed by most of the international community.

After spending the early years of his priesthood in Africa, the British priest Adrian Hastings created a storm in 1973 with an article in The Times about the "Wiriyamu Massacre" in Mozambique.

[6][7] His report was printed a week before Caetano was supposed to visit Britain to celebrate the 600th anniversary of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance.

Portugal's growing isolation following Hastings's claims has often been cited as a factor that helped to bring about the Carnation Revolution, a coup that deposed Caetano's regime in 1974.

[8] By the early 1970s, the counterinsurgency war had been won in Angola, it was less than satisfactorily contained in Mozambique and dangerously stalemated in Portuguese Guinea and so the Portuguese government decided to create sustainability policies to allow continuous sources of financing for the war effort for the long run.

In Brazil, he continued his academic activity as director of the Institute of Comparative Law at Gama Filho University in Rio de Janeiro.