Ethiopia in the Middle Ages

[2] The kingdom was an integral part of the trade route between Rome and the Indian subcontinent,[2] had substantial cultural ties to the Greco-Roman world,[3] and was a very early adopter of Christianity under Ezana of Aksum in the mid-4th century.

[2] At its height, the kingdom spanned what is now Eritrea, northern Ethiopia, eastern Sudan, Yemen and the southern part of what is now Saudi Arabia.

[10] Despite the anti-Christian nature of Gudit's takeover, Christianity flourished under Zagwe rule[11] but its territorial extent was markedly smaller than that of the Aksumites, controlling the area between Lasta and the Red Sea.

Byzantine emperor Justin I called upon Kaleb of Aksum for assistance to the Himyarite Christians, and the Aksumite invasion occurred in 525.

[21] With a Persian presence established in South Arabia, Aksum no longer dominated Red Sea trade; this situation only worsened following the Muslim conquest of Persia in the 7th century.

[22][23] The final three centuries of the Kingdom of Aksum are considered a dark age by historians, offering little in the way of written and archaeological records.

No religion or ethnic group has been decisively identified with Bani al-Hamwiyah, but the queen, who is known as Gudit, was certainly non-Christian, as her reign was characterized by the destruction of churches in Ethiopia which is seen as opposition to the spread of Christianity in the region.

[10] Though Christianity experienced growth in this period, Ethiopia's territory diminished significantly since the fall of the Kingdom of Aksum, centred primarily on the Ethiopian highlands between Lasta and Tigray.

The epic states that the Kingdom of Aksum was founded by Menelik I, who was allegedly the son of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, known as Makeda in Ethiopia.

However, both the Christian and Muslim regions of Ethiopia were significantly weakened by the war; this has been suggested as a possible factor of the Oromo migrations of the 16th century.

[17] From political, religious and cultural perspectives, the mid-16th century signifies the shift from the Middle Ages to the early modern period.

[18][1] Medieval Ethiopia is typically described as a feudal society relying on tenant farmers who constituted the peasant class, with landowners, nobility, and royalty above them in the social hierarchy.

The kings of Aksum occupied the top of the social hierarchy, and a noble class below them is probable, based on size differences between larger palaces and smaller villas.

However, Greek was used up until the decline of Aksum, appearing in stelae inscriptions, on Aksumite currency, and spoken as a lingua franca to facilitate trade with the Hellenized world.

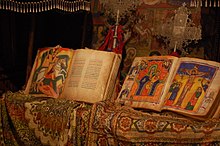

[2] Geʽez remained in official written use through the entire Middle Ages (its counterpart in Islamic polities being Arabic), but likely declined as a spoken language in the post-Aksumite period.

[36] While the appellation of "language of the king" ((Ge'ez: ልሳነ ንጉሥ "Lisane Negus")/(Amharic: የንጉሥ ቋንቋ "Ye-Negus QwanQwa")) and its use in the royal court are otherwise traced to the Amhara Emperor Yekuno Amlak.

[37][38] Prior to the adoption of Christianity, the Kingdom of Aksum practised Semitic polytheism, which spread to the region from South Arabia.

[39] It has also been suggested that Judaism was present in the kingdom since ancient times; it is not known how widely the religion was practised, but its influence upon Ethiopian Christianity is significant.

The Aksumites enjoyed friendly relations with the Byzantine Empire for this reason,[20] and although Ethiopia became secluded after the decline of Aksum, the kingdom participated in European religious and diplomatic affairs in the late Middle Ages.

Under the reign of Yeshaq I, the Beta Israel were defeated in a war; he subsequently revoked their land ownership rights (known as rist) unless they converted to Christianity.

Pastoralism was prevalent in the hot, arid lowlands; and fruiting plants, such as coffea (coffee) and false banana were grown in the wetter tropical regions.

Maritime trade continued through the Middle Ages, however this was no longer in the hands of the Ethiopian kingdom, but instead controlled by Muslim merchants.

[57] While agriculture was the backbone of the Ethiopian economy, the kingdom exported some luxury goods, namely gold, ivory, and civet musk.

This practice can be traced back to the beginning of the Aksumite period, when the men of newly subjugated tribes were forced to become soldiers for the king of Aksum, commanded by a tributary who was likely a local chief.

[59] Merid Wolde Aregay suggests, based on Christopher Ehret's linguistic theories, that the origin of Aksumite rule itself may have been through the subjugation of Agaw agriculturalists by Geʽez-speaking pastoralists.

[63] In the Solomonic era, during the reign of Zara Yaqob, this professionalism was reflected in the Amharic term č̣äwa, as ṣewa carried a connotation of slavery which was no longer accurate.

The 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius describes the Aksumite fleet as consisting of sewn boats, similar to the dhow still in use today.

[75] Ethiopian tradition dates the origins of zema to the 6th century, crediting Yared with the composition of the liturgical hymns as well as an indigenous system of musical notation called meleket.

A 16th-century royal chronicle credits two clerics with the system; this, coupled with the differences between Christian and Jewish traditions, suggest that Yared was not responsible for these creations.

[79] Buildings constructed in the Kingdom of Aksum have been subject to more research than those of the Middle Ages, leading to the identification of a discernible Aksumite architectural style.