Ethnic Chinese in Brunei

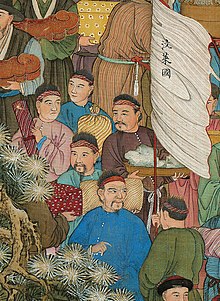

[4] Ethnic Chinese in Brunei were encouraged to settle due to their commercial and business acumen, with the largest subgroup being the Hokkien, many of whom originated from Kinmen and Xiamen in China, followed by smaller groups of Hakka and Cantonese.

Despite their relatively small numbers, the Hokkien have a significant presence in Brunei's private and business sectors, contributing their entrepreneurial expertise and often partnering with Malaysian Chinese enterprises in joint ventures.

By 1225, Brunei's significance in the Nanyang trade was highlighted by Zhao Rukuo, who noted that the country's main exports were tortoise shells and camphor, exchanged for Chinese fabrics and pottery.

[11] According to Malcolm Stewart Hannibal McArthur, the British envoy, there were approximately 500 Chinese living in Brunei in 1904, a figure nearly 20 times smaller than in 1800 (based on the lowest estimate).

According to family tradition, the first Angs arrived in Brunei before James Brooke, and in 1919, a Chinese partnership, supported financially by Cheok Boon Siok, cleared and planted the first significant tract of irrigated rice farming.

[15] Despite these developments, much of Brunei's modern industry, including coal mining in Brooketon (present-day Muara), was controlled by Westerners, particularly the Brookes, which kept the average income of Bruneian Chinese relatively modest compared to their counterparts in the Straits Settlements.

Despite a relatively gentle start to the occupation, the Chinese and Malays were subjected to harsh treatment, with many massacred in Brunei Town (now Bandar Seri Begawan).

The Pengiran Bendahara, Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin's brother, supported the Barisan Pemuda, a nationalist movement that included the radical Kumpulan Ganyang China (Group for Crushing the Chinese).

The resurgence in consumption led to the founding of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce (CCC) in 1947, and by the 1950s and 1960s, two geo-dialectal associations were established to represent the influx of Sarawakian Hakkas and Fuzhous.

[19] Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah persuaded the Legislative Council (LegCo) to eliminate the 1970 subsidies given to Catholic schools in order to demonstrate the Islamic aspect of Bruneian society.

The Sultan attended the CCC's annual banquet and appointed Chinese Bruneian Lim Jock Seng as secretary for ASEAN affairs, recognising his contributions.

At that time, 25% of Chinese workers were employed in highly skilled occupations such as management, law, and administration, 30% in specialised fields such as technology and clerical work, and 30% in the retail trade and craft industries.

Despite regulations limiting foreign staff, Chinese Bruneians now hold senior roles in the financial sector, even though Chinese-owned institutions faced setbacks, such as the bankruptcies of the 1980s.

[26] At the annual meeting of the LegCo in 2015, Goh King Chin, a member of the parliament, suggested amending the Brunei Nationality Act and providing provisions for citizenship to stateless people 60 years of age and older.

But in the end, this proposal was rejected by Abu Bakar Apong, the minister of home affairs, who said that the existing nationality regulations were adequate and that stateless people were provided official travel credentials in lieu of passports.

This creates a disparity: the Brunei Nationality Act (1961) automatically grants citizenship to recognised Malay indigenous communities, while non-Malays must apply through registration or naturalisation.

Stateless Chinese must meet strict requirements to apply for citizenship, including passing a notoriously difficult Malay language test and residing in the country for 20 out of the past 25 years.

Stateless individuals, recognised as permanent residents through their purple identity cards, are allowed to live in the country but are excluded from key citizenship privileges such as property ownership, obtaining a passport, and accessing government benefits.

Despite their relatively small numbers, the Hokkien community has a significant presence in Brunei’s private and business sectors, playing a key role in the country's commercial landscape and frequently collaborating with Malaysian Chinese enterprises in joint ventures.

The LegCo also had Chinese members such Yap Chung Teck, Chong Seng Toh, Hong Kok Tin, Othman @ Chua Kwang Soon, and George Newn Ah Foot.

For instance, Ong Boon Pang was appointed Kapitan Cina by the sultan in 1932, and later, Lim Cheng Choo played a key role in drafting Brunei's 1959 constitution and signed the 1979 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation.

Several other Bruneian Chinese have permanent secretarial positions, such as in the Ministries of Finance and Foreign Affairs, while Paul Kong serves as the General Assurance Association's acting chairman.

First, to incorporate the modern administrative elite into the hierarchical structure of traditional Bruneian society, commoners holding government offices are granted titles such as "Pehin" or "Dato".

[43][f] These include the Onn Siew Siong, based in Kuala Belait, and Lau Ah Kok and Goh King Chin, both of whom were formerly members of the LegCo and now reside in the Brunei–Muara District.

Chinese Bruneian fiction, such as K. H. Lim's Written in Black, reflects the intricate cultural dynamics of the society by examining topics of identity, migration, and familial life.

[45] In addition to providing social commentary, these literary works capture the experiences of the Chinese population, such as the difficulties associated with mental health issues and statelessness.

[34]With Taoist temples spread across all four districts and Protestant and Catholic Christian churches in Bandar Seri Begawan, Seria, and Kuala Belait, the Chinese community in Brunei is granted religious freedom under the 1959 constitution.

Furthermore, it is not unusual for Chinese Bruneians to convert to Islam, which reflects the religious variety of the country and the cultural assimilation taking place within the context of Brunei's MIB ideology.

Many Chinese people may view such a conversion as a rejection of their ethnic heritage and individualistic ideals when the convert sheds their prior selfish behaviours and takes on a new identity while embracing Islamic principles.

[48] Following the liberalisation of Brunei's education policy, private schools were allowed to offer Chinese language classes, though these are often basic due to limited resources and teaching methods.