Etruscan architecture

The Etruscans were considerable builders in stone, wood and other materials of temples, houses, tombs and city walls, as well as bridges and roads.

The only structures remaining in quantity in anything like their original condition are tombs and walls, but through archaeology and other sources we have a good deal of information on what once existed.

But increasingly, from about 200 BC, the Romans looked directly to Greece for their styling, while sometimes retaining Etruscan shapes and purposes in their buildings.

[3] The early Etruscans seem to have worshipped in open air enclosures, marked off but not built over; sacrifices continued to be performed outside rather than inside temples in traditional Roman religion until its end.

The only written account of significance on their architecture is by Vitruvius (died after 15 BC), writing some two centuries after the Etruscan civilization was absorbed by Rome.

[9] Nonetheless, Vitruvius remains the inevitable starting point for a description, and a contrast of Etruscan temples with their Greek and Roman equivalents.

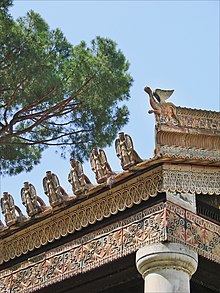

Remains of the architectural terracotta elements sometimes survive in considerable quantities, and museums, mostly in Italy, have good collections of attractively shaped and painted antefixes in particular.

[10] Vitruvius specifies three doors and three cellae, one for each of the main Etruscan deities, but archaeological remains do not suggest this was normal, though it is found.

[15] Substantial but broken remains of late sculptured pediment groups survive in museums, in fact rather more than from Greek or Roman temples, partly because the terracotta was not capable of "recycling" as marble was.

[16] Features shared by typical Etruscan and Roman temples, and contrasting with Greek ones, begin with a strongly frontal approach, with great emphasis on the front facade, less on the sides, and very little on the back.

[17] In Etruscan temples, more than Roman ones, the portico is deep, often representing, as Vitruvius recommends, half of the area under the roof, with multiple rows of columns.

For the first temple Etruscan specialists were brought in for various aspects of the building, including making and painting the extensive terracotta elements of the entablature or upper parts, such as antefixes.

One obvious possible function is as palatial dwellings; another is as civic buildings, acting as places for assembly, and commemoration of aspects of the community.

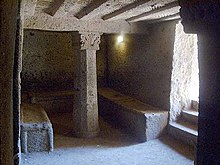

The rock-cut tomb chambers often form suites of "rooms", some quite large, which presumably resemble in part the atrium homes of the better-off Etruscans.

These were apparently used to hold cremated ashes, and are found in the Etruscan Iron Age Villanovan culture and early burials, especially in northern areas.

[36] The site cannot be identified with certainty, but at one candidate location circle of six post-holes plus a central one have been found, cut into the tufa bedrock, with an ovoid 4.9m x 3.6m perimeter.

Some types clearly replicate aspects of the richer houses, with a number of connected chambers, columns with capitals, and rock-cut ceilings given beams.

The Romans considered the sulcus primigenius—the sanctification of the course of a future city wall through a ritual plowing—to have been a continuation of similar Etruscan practices.

Even before the Romans began to swallow up Etruscan territory, Italy had frequent wars, and by the later period had Celtic enemies to the north, and an expanding Rome to the south.

Their construction may have mainly resulted from the wearing through soft tufo bedrock by iron-rimmed wheels, creating deep ruts that required the road to be frequently recut to a smooth surface.

[47] The 7th and 6th centuries BC show a move to replace earlier tracks only suitable for mules and pedestrians with wider and more engineered roads capable of taking wheeled vehicles, using gentler but longer routes through hilly country.