Etymologiae

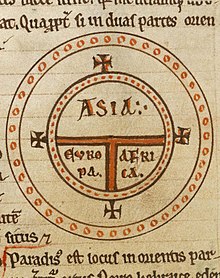

Etymologiae (Latin for 'Etymologies'), also known as the Origines ('Origins'), usually abbreviated Orig., is an etymological encyclopedia compiled by the influential Christian bishop Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636) towards the end of his life.

Etymologiae summarized and organized a wealth of knowledge from hundreds of classical sources; three of its books are derived largely from Pliny the Elder's Natural History.

Etymology, the origins of words, is prominent, but the work also covers, among other things, grammar, rhetoric, mathematics, geometry, music, astronomy, medicine, law, the church and heretical sects, pagan philosophers, languages, cities, humans, animals, the physical world, geography, public buildings, roads, metals, rocks, agriculture, war, ships, clothes, food, and tools.

It was cited by Dante Alighieri (who placed Isidore in his Paradiso), quoted by Geoffrey Chaucer, and mentioned by the poets Boccaccio, Petrarch, and John Gower.

Isidore helped to unify the kingdom through Christianity and education, eradicating the Arian heresy which had been widespread, and led National Councils at Toledo and Seville.

He was familiar with the works of both the church fathers and pagan writers such as Martial, Cicero and Pliny the Elder, this last the author of the major encyclopaedia then in existence, the Natural History.

The classical encyclopedists had already introduced alphabetic ordering of topics, and a literary rather than observational approach to knowledge: Isidore followed those traditions.

[6] An analysis of Book XII by Jacques André identifies 58 quotations from named authors and 293 borrowed but uncited usages: 79 from Solinus; 61 from Servius; 45 from Pliny the Elder.

But his translator Stephen Barney notes as remarkable that he never actually names the compilers of the encyclopedias that he used "at second or third hand",[7] Aulus Gellius, Nonius Marcellus, Lactantius, Macrobius, and Martianus Capella.

Barney further notes as "most striking"[7] that Isidore never mentions three out of his four principal sources (the one he does name being Pliny): Cassiodorus, Servius and Solinus.

Books XII, XIII and XIV are largely based on the Natural History and Solinus, whereas the lost Prata of Suetonius, which can be partly pieced together from what is quoted in the Etymologiae, seems to have inspired the general plan of the work, as well as many of its details.

He covers the letters of the alphabet, parts of speech, accents, punctuation and other marks, shorthand and abbreviations, writing in cipher and sign language, types of mistake and histories.

[14] Book III covers the medieval Quadrivium, the four subjects that supplemented the Trivium being arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

The first deals with the horoscope and the attempt of foreseeing the future of one or more persons; the latter was a legitimate activity which had concerns with meteorological predictions, including iatromathematics and astrological medicine.

He derives the word medicine from the Latin for "moderation" (modus), and "sciatica" (sciasis) from the affected part of the body, the hip (Greek ἰσχία ischia).

On chronology, Isidore covers periods of time such as days, weeks, and months, solstices and equinoxes, seasons, special years such as Olympiads and Jubilees, generations and ages.

[21] Book VII describes the basic scheme concerning God, angels, and saints: in other words, the hierarchies of heaven and earth from patriarchs, prophets and apostles down the scale through people named in the gospels to martyrs, clergymen, monks and ordinary Christians.

[27] Book XIII describes the physical world, atoms, classical elements, the sky, clouds, thunder and lightning, rainbows, winds, and waters including the sea, the Mediterranean, bays, tides, lakes, rivers and floods.

[44] Isidore was widely influential throughout the Middle Ages, feeding directly into word lists and encyclopaedias by Papias, Huguccio, Bartholomaeus Anglicus and Vincent of Beauvais, as well as being used everywhere in the form of small snippets.

He was cited by Dante Alighieri, quoted by Geoffrey Chaucer, and his name was mentioned by the poets Boccaccio, Petrarch and John Gower among others.

[48] In the view of John T. Hamilton, writing in The Classical Tradition in 2010, "Our knowledge of ancient and early medieval thought owes an enormous amount to this encyclopedia, a reflective catalogue of received wisdom, which the authors of the only complete translation into English introduce as "arguably the most influential book, after the Bible, in the learned world of the Latin West for nearly a thousand years"[49] These days, of course, Isidore and his Etymologies are anything but household names... but the Vatican has named Isidore the patron saint of the Internet, which is likely to make his work slightly better known.

[50] Ralph Hexter, also writing in The Classical Tradition, comments on "Isidore's largest and massively influential work... on which he was still at work at the time of his death... his own architecture for the whole is relatively clear (if somewhat arbitrary)... At the deepest level Isidore's encyclopedia is rooted in the dream that language can capture the universe and that if we but parse it correctly, it can lead us to the proper understanding of God's creation.

"[45] Writing in The Daily Telegraph, Peter Jones compares Etymologiae to the Internet: One might have thought that Isidore, Bishop of Seville, AD 600-636, had already suffered enough by having Oxford's computerised 'student administration project', planned since 2002, named after him.

But five years ago Pope John Paul II compounded his misfortune by proposing (evidently) to nominate [Isidore] as the patron saint of the internet.

Isidore's Etymologies, published in 20 books after his death, was an encyclopedia of all human knowledge, glossed with his own derivations of the technical terms relevant to the topic in hand.

By the same token, Isidore's work was phenomenally influential throughout the West for 1,000 years, 'a basic book' of the Middle Ages, as one scholar put it, second only to the Bible.

Written in simple Latin, it was all a man needed in order to have access to everything he wanted to know about the world but never dared to ask, from the 28 types of common noun to the names of women's outer garments.

The earliest is held at the Abbey library of Saint Gall in Switzerland,[46] a 9th-century copy of Books XI to XX forming part of the Codex Sangallensis.