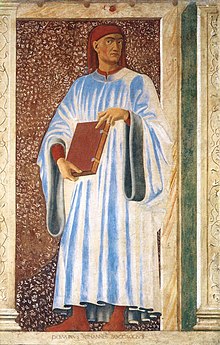

Giovanni Boccaccio

Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was sometimes simply known as "the Certaldese"[2] and one of the most important figures in the European literary panorama of the fourteenth century.

Some scholars (including Vittore Branca) define him as the greatest European prose writer of his time, a versatile writer who amalgamated different literary trends and genres, making them converge in original works, thanks to a creative activity exercised under the banner of experimentalism.

Bocaccio wrote his imaginative literature mostly in Tuscan vernacular, as well as other works in Latin, and is particularly noted for his realistic dialogue which differed from that of his contemporaries, medieval writers who usually followed formulaic models for character and plot.

The influence of Boccaccio's works was not limited to the Italian cultural scene but extended to the rest of Europe, exerting influence on authors such as Geoffrey Chaucer,[3] a key figure in English literature, and the later writers Miguel de Cervantes, Lope de Vega and classical theatre in Spain.

[4] He is remembered for being one of the precursors of humanism, of which he helped lay the foundations in the city of Florence, in conjunction with the activity of his friend and teacher Petrarch.

In the twentieth century, Boccaccio was the subject of critical-philological studies by Vittore Branca and Giuseppe Billanovich, and his Decameron was transposed to the big screen by the director and writer Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Works produced in this period include Il Filostrato and Teseida (the sources for Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde and The Knight's Tale, respectively), The Filocolo (a prose version of an existing French romance), and La caccia di Diana (a poem in terza rima listing Neapolitan women).

[10] The period featured considerable formal innovation, including possibly the introduction of the Sicilian octave, where it influenced Petrarch.

Boccaccio returned to Florence in early 1341, avoiding the plague of 1340 in that city, but also missing the visit of Petrarch to Naples in 1341.

In Florence, the overthrow of Walter of Brienne brought about the government of popolo minuto ("small people", workers).

He also pushed for the study of Greek, housing Barlaam of Calabria, and encouraging his tentative translations of works by Homer, Euripides, and Aristotle.

They met again in Padua in 1351, Boccaccio on an official mission to invite Petrarch to take a chair at the university in Florence.

Although unsuccessful, the discussions between the two were instrumental in Boccaccio writing the Genealogia deorum gentilium; the first edition was completed in 1360 and this remained one of the key reference works on classical mythology for over 400 years.

Thus, he challenged the arguments of clerical intellectuals who wanted to limit access to classical sources to prevent any moral harm to Christian readers.

The revival of classical antiquity became a foundation of the Renaissance, and his defence of the importance of ancient literature was an essential requirement for its development.

Certain sources also see a conversion of Boccaccio by Petrarch from the open humanist of the Decameron to a more ascetic style, closer to the dominant fourteenth-century ethos.

[19] Bocaccio's final years were troubled by illnesses, some relating to obesity and what often is described as dropsy, severe edema that would be described today as congestive heart failure.