Euchambersia

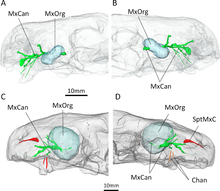

In 2017, the internal structure of the skull of E. mirabilis has been used as stronger evidence in favour of the hypothesis that it was venomous; other possibilities, such as the indentation supporting some sort of sensory organ, still remain plausible.

They originated from the same general layer of rock, in the upper Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone of the Beaufort Group within the Karoo Supergroup.

[1] The second species, E. liuyudongi, was named by Jun Liu and Fernando Abdala in 2022 based on a well-preserved skull with an associated lower jaw, catalogued as IVPP V 31137.

[6] Liu and colleagues had previously described a number of other new species from the middle portion of the Naobaogou Formation, which were among the 80 specimens that had been excavated from at least three field seasons after 2009.

The branches of the postorbital and jugal that usually surround the back and bottom of the eye socket in therocephalians appear to be either very reduced or absent entirely.

[2] Like other therocephalians, its canine was very large, resulting in a specialized predatory lifestyle that incorporates a sabertooth bite into prey killing.

The bottom portion of the fossa is strongly pitted and bears a small opening, or foramen, on both the front and back surfaces.

[6] CT scanning shows that the openings of E. mirabilis lead to canals that connect to the trigeminal nerve, which controls facial sensitivity.

[15][16] Boonstra initially misspelt the name as Euchambersidae (which is improper Latin), and was subsequently corrected by Friedrich von Huene in 1940.

[17] The 1986 phylogenetic analysis of James Hopson and Herb Barghusen supported Mendez's hypothesis of three subfamilies within Moschorhinidae, but they elected to use the name Euchambersiidae.

[6] Lycosuchus Gorynychus Scylacosauridae Scylacosuchus Ophidostoma Hofmeyria Ictidostoma Mirotenthes Whaitsiidae Baurioidea Chthonosauridae Annatherapsidus Shiguaignathus Jiufengia

[21] This hypothesis was widely accepted throughout the 20th century[18][22][23][24] and the characteristic morphology of Euchambersia was used to support possible venom-bearing adaptations among various other prehistoric animals,[10][25][26] including the related therocephalians Megawhaitsia[16] and Ichibengops.

[24] This interpretation, which has consistently appeared in literature published after 1986, was determined by Julien Benoit to be the result of the propagation of Broom's overly reconstructed diagram of the skull, without the context of the actual specimens.

[3] Additionally, Benoit argued that grooved and ridged canines are not necessarily associated with venomous animals either, as shown by their presence in hippopotami, muntjacs, and baboons, in which they play a role in grooming or sharpening the teeth;[3][24][28] in the latter two, ridged canines are also accompanied by a distinct fossa in front of the eye, which is entirely unconnected with venom.

[24][29] Furthermore, grooved and ridged teeth in non-venomous snakes are used to reduce suctional drag when capturing slippery prey like fish or invertebrates.

[30] CT scanning of the known specimens of Euchambersia by Benoit and colleagues was subsequently used to provide more concrete support in favour of the venom hypothesis.

The canals leading into and from the maxillary fossae, as revealed by the scans, would primarily have supported the trigeminal nerve as well as blood vessels.

[2][37] An alternate hypothesis suggested by Benoit et al. involves some kind of sensory organ occupying the maxillary fossa.

[41] In the Cistecephalus AZ, other co-occurring therocephalians included Hofmeyria, Homodontosaurus, Ictidostoma, Ictidosuchoides, Ictidosuchops, Macroscelesaurus, Polycynodon, and Proalopecopsis.

More numerous, however, were the gorgonopsians, which included Aelurognathus, Aelurosaurus, Aloposaurus, Arctognathus, Arctops, Cerdorhinus, Clelandina, Cyonosaurus, Dinogorgon, Gorgonops, Lycaenops, Leontocephalus, Pardocephalus, Prorubidgea, Rubidgea, Scylacops, Scymnognathus, and Sycosaurus.

Other dicynodonts included Aulacephalodon, Cistecephalus, Dicynodon, Dicynodontoides, Digalodon, Dinanomodon, Emydops, Endothiodon, Kingoria, Kitchinganomodon, Oudenodon, Palemydops, Pelanomodon, Pristerodon, and Rhachiocephalus.

Non-synapsids included the archosauromorph Younginia; the parareptilians Anthodon, Milleretta, Nanoparia, Owenetta, and Pareiasaurus; and the temnospondyl Rhinesuchus.

Subsequently, Liu and Abdala confirmed their presence in the formation by describing two other akidnognathids besides E. liuyudongi, Shiguaignathus[7] and Jiufengia,[44] as well as Caodeyao, a non-akidnognathid therocephalian closely related to the Russian Purlovia.