Zoning in the United States

[7][8] Zoning ordinances did not allow African-Americans moving into or using residences that were occupied by majority whites due to the fact that their presence would decrease the value of home.

[7] The housing shortage in many metropolitan areas, coupled with racial residential segregation, has led to increased public focus and political debates on zoning laws.

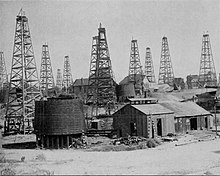

The purported need for formal zoning in America arose at the turn of the twentieth century as cities such as New York, experiencing rapid urbanization and growth in industry, felt a growing need to reduce congestion, stabilize property values, combat poor urban design,[33] and protect residents from issues such as crowded living conditions, outbreaks of disease, and industrial pollution,[3] through legal means.

Edward M. Bassett, author of the first comprehensive zoning ordinance in the United States, wrote in 1922:Skyscrapers would be built to unnecessary height, their cornices projecting into the street and shutting out light and air.

Transit and street facilities were overwhelmed...[33]Additionally, many of the earliest zoning laws in the United States were influenced by a demand for class,[2] ethnic, and race-based segregation.

[39] However, between 1909 and 1915, Los Angeles City Council responded to some requests by business interests to create exceptions to industrial bans within the three residential districts.

Even after the Georgia Supreme Court struck down the Atlanta ordinance, the city continued to use their racially based residential zoning maps.

Other municipalities tested the limits of Buchanan; Florida, Apopka and West Palm Beach drafted race-based residential zoning ordinances.

Among the members of this committee were Edward Bassett, Alfred Bettman, Morris Knowles, Nelson Lewis, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., and Lawrence Veiller.

The zoning ordinance of Euclid, Ohio was challenged in court by a local land owner on the basis that restricting use of property violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Ambler Realty Company filed suit on November 13, 1922, against the Village of Euclid, Ohio, alleging that the local zoning ordinances effectively diminished its property values.

Nonetheless, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed that decision, holding that zoning was a nuisance-preventing device, and as such a proper exercise of the state regulatory police power.

[65] In 2012, Democratic governor Deval Patrick expanded 40R with Compact Neighborhoods, incentivizing zoning for denser, multifamily housing near rail and transit hubs across the Commonwealth.

[67] On December 7, 2018, Minneapolis in Minnesota became the first U.S. city to decide to completely phase out exclusionary single-family zoning policies (then covering 70% of its residential land) in three stages.

[63] The House Bill 2001, adopted by the Oregon Senate in a 17–9 vote on June 30, 2019, effectively eliminated single-family zoning in large Oregonian cities.

[78] Beginning in 1987, several United States Supreme Court cases ruled against land use regulations as being a taking requiring just compensation pursuant to the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.

First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. Los Angeles County ruled that even a temporary regulatory taking may require compensation.

Nollan v. California Coastal Commission ruled that construction permit conditions that fail to substantially advance the agency's authorized purposes, require compensation.

In the Atlanta suburb of Roswell, Georgia, an ordinance banning billboards was overturned in court the grounds that it unconstitutionally violated the right to freedom of speech.

Congress enacted the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) in 2000, however, in an effort to correct the constitutionally objectionable problems of the RFRA.

[83] In early 2022, the town of Woodside, California drew widespread derision for declaring itself a "mountain lion habitat" to avoid state affordable housing requirements.

[86] Zoning codes have evolved over the years as urban planning theory has changed, legal constraints have fluctuated, and political priorities have shifted.

[citation needed] The standard applied to the amendment to determine whether it may survive judicial scrutiny is the same as the review of a zoning ordinance: whether the restriction is arbitrary or whether it bears a reasonable relationship to the exercise of the police power of the state.

[citation needed] If the residents in the targeted neighborhood complain about the amendment, their argument in court does not allow them any vested right to keep the zoned district the same.

The inherent danger of zoning, as a coercive force used against property owners seeking to build integrated housing, has been described in detail in Richard Rothstein's book The Color of Law (2017).

[44]: 85–92 Government zoning was used significantly as an instrument to advance racism through enforced segregation in all regions of the U.S., not only in the South, from the early part of the 20th century up until recent decades.

[96] One mechanism for this is zoning by many suburban and exurban communities for very large minimum residential lot and building sizes in order to preserve home values by limiting the total supply of housing, which thereby excludes poorer people.

According to the Manhattan Institute, as much as half of the price paid for housing in some jurisdictions is directly attributable to the hidden costs of restrictive zoning regulation.

Nonetheless, a single-family home and car are major parts of the "American Dream" for nuclear families, and zoning laws often reflect this: in some cities, houses that do not have an attached garage have been deemed "blighted" and are subject to redevelopment.

[35] Localities prohibited duplexes, small homes, and multi-family buildings, which were more likely to be occupied by racial minorities, recent immigrants, and poor households.