Eugenio Espejo

Francisco Javier Eugenio de Santa Cruz y Espejo[a] (Royal Audiencia of Quito, February 21, 1747 – December 28, 1795) was a medical pioneer, writer and lawyer of criollo origin in colonial Ecuador.

Obrajes—a type of textile factory—had provided jobs, but now found themselves in decline, mainly due to a crackdown on smuggled European cloths and a series of natural disasters.

[3] In the Royal Audiencia, the education situation worsened after of the expulsion of the Jesuit priests; too few learned people lived in Quito to be able to fill the void.

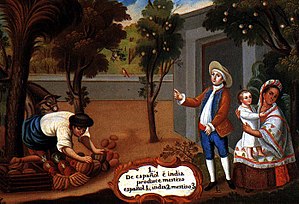

[5] In Quito at the time, ethnic prejudice was common, and therefore most people considered society to be divided into estates of the realm, which differed by racial origin.

This explained the abundance of the clergy in a small city like Quito; often men were ordained not because of a vocation but because it solved their economic problems and improved their community standing.

El Nuevo Luciano de Quito was written in dialogues, in order to present his ideas to the common people in an easy way, instead of using tedious explanations meant for scholars.

In 1781 he wrote La ciencia blancardina, which he referred to as the second part of Nuevo Luciano, as an answer to the criticism of a Mercedarian priest from Quito.

"[18] To get rid of him, the authorities named him head physician for the scientific expedition of Francisco de Requena to the Pará and Marañon rivers to set the limits of the Audiencia.

[22] Instead of recognition, Espejo acquired enemies because his work criticized the physicians and priests in charge of public health in the Royal Audiencia for their negligence, and he was forced to leave Quito.

On his way to Lima, he stopped in Riobamba, where a group of priests asked him to write a reply to a report written by Ignacio Barreto, chief tax collector.

Espejo gladly accepted the task because he wanted to settle accounts with Barreto and other citizens of Riobamba, among them José Miguel Vallejo, who had turned him in to the authorities when he tried to flee Requena's expedition to the Marañón river.

[26] The Sociedad Económica de los Amigos del País (Economic Society of Friends of the Country) was a private association established in various cities throughout Enlightenment Spain and, to a lesser degree, in some of her colonies.

[26] In 1790, Espejo returned to Quito to promote the "Sociedad Patriótica" (Patriotic Society), and on November 30, 1791, a branch was established in the Colegio de los Jesuitas; he was elected director and formed four commissions.

He understood that reading was basic in the formation of the self, and his conscience drove him to critiques of the establishment, based on observation and in the application of the law of his time.

[30] However, Espejo was one of the few people at the time who distinguished between the actual deeds of the French Revolution and the irreligious spirit connected to it, while his contemporaries in Spain and the colonies erroneously identified the emancipation of the Americas with loss of the Catholic faith.

Espejo argued that the people of Quito were accustomed to adulation and that they admired any preacher who could quote the Bible in a pompous and insubstantial way.

La ciencia blancardina, in which Espejo claimed to be the author of the previous two works, condemned the results of the clergy's educational system: ignorance and affectation.

Ecuadorian historian and cleric Federico González Suárez considered these sermons worthy of study, even though he mentioned that they lacked an "evangelic spirit.

As many thinkers realized the power of economics as a social force, Espejo, influenced by Feijoo and Adam Smith among others, showed his desire for commercial and agricultural reforms, especially conservation and proper use of land.

In the third part he showed that many workers benefited from the quinine industry, that without it there would be unemployment and unrest, and that the Crown should designate officials to regulate the proper cultivation of the cinchona tree, including reforestation.

Therefore, he implied that Barreto's own conduct was outrageous because of his excesses in collecting taxes and his habit of paying public funds to licentious women.

[47] It appears that Espejo was motivated more by the opportunity to attack his personal enemies in this work than to analyze the case and defend the clergy of Riobamba.

Still, his talent as a lawyer can be seen in his Representaciones (Representations), which caused him to be freed after his arrest in 1787 for his supposed authorship of El Retrato de Golilla.

[48] In these documents, he defended his loyalty to the Crown, commented on the unfairness of his captivity by mentioning the indignation that many distinguished men felt about his arrest, and clarified his writing goals.

This served him as a prelude to his main subject: denying being the author of El Retrato de Golilla The Spanish Crown was deeply concerned with public health.

It refuted the common belief that the separation and destruction of contaminated clothes was impractical, and it promoted personal hygiene among the people of Quito.

He understood the current European medical theories about contagious diseases and warned against the incorrect belief that smallpox was transmitted by polluted air.

^ Freile maintains that the notion of Espejo's indigenous origins sustained by most modern historians comes from their interpretation of the claims made against him by his contemporary enemies, who called him "indio" (Indian) in order to slander him in a racist society.

e. ^ Its full name is Marco Porcio Catón o Memorias para la impugnación del nuevo Luciano de Quito.

g. ^ The authorities finally found evidence against Espejo when his brother, Juan Pablo, told his lover, Francisca Navarrete, about the plans of Eugenio.