European Coal and Steel Community

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was a European organization created after World War II to integrate Europe's coal and steel industries into a single common market based on the principle of supranationalism which would be governed by the creation of a High Authority which would be made up of appointed representatives from the member states who would not represent their national interest, but would take and make decisions in the general interests of the Community as a whole.

[2] It was formally established in 1951 by the Treaty of Paris, signed by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany and was generally seen as the first step in the process of European integration following the end of the Second World War in Europe.

Despite stiff ultra-nationalist, Gaullist and communist opposition, the French Assembly voted a number of resolutions in favour of his new policy of integrating Germany 9 a community.

"[6] Portraying the coal and steel industries as integral to the production of munitions,[8] Schuman proposed that uniting these two industries across France and Germany under an innovative supranational system (that also included a European anti-cartel agency) would "make war between France and Germany [...] not only unthinkable but materially impossible".

[11]: 210 The single market was to be supervised by a High Authority, with powers to handle extreme shortages of supply or demand, to tax, and to prepare production forecasts as guidelines for investment.

[11]: 210 A key issue in the negotiations for the treaty was the break-up of the excessive concentrations in the coal and steel industries of the Ruhr, where the Konzerne, or trusts, had underlain the military power of the former Reich.

[11]: 213 Also, Raymond Vernon (of later fame for his studies on industrial policy at Harvard university) was passing every clause of successive drafts of the treaty under his microscope down in the bowels of the State Department.

[11]: 215 In West Germany, Karl Arnold, the Minister President of North Rhine-Westphalia, the state that included the coal and steel producing Ruhr, was initially spokesman for German foreign affairs.

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (German: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD), in spite of support from unions and other socialists in Europe, decided it would oppose the Schuman plan.

Kurt Schumacher's personal distrust of France, capitalism, and Konrad Adenauer aside, he claimed that a focus on integrating with a "Little Europe of the Six" would override the SPD's prime objective of German reunification and thus empower ultra-nationalist and Communist movements in democratic countries.

He also thought the ECSC would end any hopes of nationalising the steel industry and lock in a Europe of "cartels, clerics and conservatives".

[13] Younger members of the party like Carlo Schmid, were, however, in favor of the Community and pointed to the long socialist support for the supranational idea.

Notable amongst these were ministerial colleague Andre Philip, president of the Foreign Relations Committee Edouard Bonnefous, and former prime minister, Paul Reynaud.

Projects for a coal and steel authority and other supranational communities were formulated in specialist subcommittees of the Council of Europe in the period before it became French government policy.

Charles de Gaulle, who was then out of power, had been an early supporter of "linkages" between economies, on French terms, and had spoken in 1945 of a "European confederation" that would exploit the resources of the Ruhr.

It gained strong majority votes in all eleven chambers of the parliaments of the Six, as well as approval among associations and European public opinion.

The Council of Europe, created by a proposal of Schuman's first government in May 1948, helped articulate European public opinion and gave the Community idea positive support.

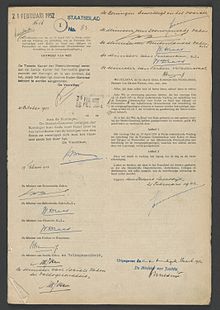

'[15][16] The 100-article Treaty of Paris, which established the ECSC, was signed on 18 April 1951 by "the inner six": France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

The ECSC was based on supranational principles[2] and was, through the establishment of a common market for coal and steel, intended to expand the economy, increase employment, and raise the standard of living within the Community.

A Consultative Committee was established alongside the High Authority, as a fifth institution representing producers, workers, consumers and dealers (article 18).

Their independence was aided by members being barred from having any occupation outside the Authority or having any business interests (paid or unpaid) during their tenure and for three years after they left office.

The Authority had a broad area of competence to ensure the objectives of the treaty were met and that the common market functioned smoothly.

[25] The Common Assembly (the forerunner to the European Parliament) was composed of 78 representatives: 18 from each of France, Germany, and Italy; 10 from Belgium and the Netherlands; and 4 from Luxembourg (article 21).

It commences quoting the French Government Proposal of Schuman: "World peace cannot be safeguarded without creative measures commensurate with the dangers which threaten it."

[32] Writing in Le Monde in 1970, Gilbert Mathieu argued the Community had little effect on coal and steel production, which was influenced more by global trends.

He argues that the "pool" did not prevent the resurgence of large coal and steel groups, such as the Konzerne, which helped Adolf Hitler build his war machine.

The ECSC also paid half the occupational redeployment costs of those workers who had lost their jobs as coal and steel facilities began to close down.

[34] Far more important than creating Europe's first social and regional policy, Robert Schuman argued that the ECSC introduced European peace.