Basque language

[12] As a part of this process, a standardised form of the Basque language, called Euskara Batua, was developed by the Euskaltzaindia in the late 1960s.

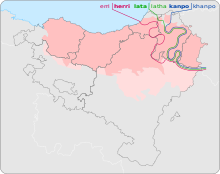

Besides its standardised version, the five historic Basque dialects are Biscayan, Gipuzkoan, and Upper Navarrese in Spain and Navarrese–Lapurdian and Souletin in France.

Typologically, with its agglutinative morphology and ergative–absolutive alignment, Basque grammar remains markedly different from that of Standard Average European languages.

[15] The Spanish term vascuence, derived from Latin vasconĭce,[16] has acquired negative connotations over the centuries and is not well-liked amongst Basque speakers generally.

Its use is documented at least as far back as the 14th century when a law passed in Huesca in 1349 stated that Item nuyl corridor nonsia usado que faga mercadería ninguna que compre nin venda entre ningunas personas, faulando en algaravia nin en abraych nin en basquenç: et qui lo fara pague por coto XXX sol—essentially penalising the use of Arabic, Hebrew, or Basque in marketplaces with a fine of 30 sols (the equivalent of 30 sheep).

Authors such as Miguel de Unamuno and Louis Lucien Bonaparte have noted that the words for "knife" (aizto), "axe" (aizkora), and "hoe" (aitzur) appear to derive from the word for "stone" (haitz), and have therefore concluded that the language dates to prehistoric Europe when those tools were made of stone.

Latin inscriptions in Gallia Aquitania preserve a number of words with cognates in the reconstructed proto-Basque language, for instance, the personal names Nescato and Cison (neskato and gizon mean 'young girl' and 'man', respectively in modern Basque).

This language is generally referred to as Aquitanian and is assumed to have been spoken in the area before the Roman Republic's conquests in the western Pyrenees.

Initially the source was Latin, later Gascon (a branch of Occitan) in the north-east, Navarro-Aragonese in the south-east and Spanish in the south-west.

Apart from pseudoscientific comparisons, the appearance of long-range linguistics gave rise to several attempts to connect Basque with geographically very distant language families such as Georgian.

Some of these hypothetical connections are: The region where Basque is spoken has become smaller over centuries, especially at the northern, southern, and eastern borders.

Nothing is known about the limits of this region in ancient times, but on the basis of toponyms and epigraphs, it seems that in the beginning of the Common Era it stretched to the river Garonne in the north (including the south-western part of present-day France); at least to the Val d'Aran in the east (now a Gascon-speaking part of Catalonia), including lands on both sides of the Pyrenees;[35] the southern and western boundaries are not clear at all.

The Reconquista temporarily counteracted this contracting tendency when the Christian lords called on northern Iberian peoples — Basques, Asturians, and "Franks" — to colonise the new conquests.

In the Spanish part, Basque-language schools for children and Basque-teaching centres for adults have brought the language to areas such as western Enkarterri and the Ribera del Ebro in southern Navarre, where it is not known to ever have been widely spoken; and in the French Basque Country, these schools and centres have almost stopped the decline of the language.

For instance, the fuero or charter of the Basque-colonised Ojacastro (now in La Rioja) allowed the inhabitants to use Basque in legal processes in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The language has official status in those territories that are within the Basque Autonomous Community, where it is spoken and promoted heavily, but only partially in Navarre.

[47][48][49][50][51] Although a number of words of alleged Basque origin in the Spanish language are circulated (e.g. anchoa 'anchovies', bizarro 'dashing, gallant, spirited', cachorro 'puppy', etc.

[15] Ignoring cultural terms, there is one strong loanword candidate, ezker, long considered the source of the Pyrenean and Iberian Romance words for "left (side)" (izquierdo, esquerdo, esquerre).

[56] The Algonquian–Basque pidgin arose from contact between Basque whalers and the Algonquian peoples in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and Strait of Belle Isle.

As a result, gizon 'man' becomes gixon 'little fellow', zoro 'crazy, insane' becomes xoro 'silly, foolish', and bildots 'lamb' becomes bildotx 'lambkin, young lamb'.

This scheme provides Basque with a distinct musicality that differentiates its sound from the prosodical patterns of Spanish (which tends to stress the second-to-last syllable).

The pronoun hi is used for both of them, but where the masculine form of the verb uses a -k, the feminine uses an -n. This is a property rarely found in Indo-European languages.

Through contact with neighbouring peoples, Basque has adopted many words from Latin, Spanish, French and Gascon, among other languages.

There are a considerable number of Latin loans (sometimes obscured by being subject to Basque phonology and grammar for centuries), for example: lore ("flower", from florem), errota ("mill", from rotam, "[mill] wheel"), gela ("room", from cellam), gauza ("thing", from causa).

Hence, Ikurriña can also be written Ikurrina without changing the sound, whereas the proper name Ainhoa requires the mute ⟨h⟩ to break the palatalisation of the ⟨n⟩.

⟨h⟩ is mute in most regions, but it is pronounced in many places in the north-east, the main reason for its existence in the Basque alphabet.

Its acceptance was a matter of contention during the standardisation process because the speakers of the most extended dialects had to learn where to place ⟨h⟩, silent for them.

Esklabu erremintaria Sartaldeko oihanetan gatibaturik Erromara ekarri zinduten, esklabua, erremintari ofizioa eman zizuten eta kateak egiten dituzu.

Labetik ateratzen duzun burdin goria nahieran molda zenezake, ezpatak egin ditzakezu zure herritarrek kateak hauts ditzaten, baina zuk, esklabu horrek, kateak egiten dituzu, kate gehiago.

IPA pronunciation [s̺artaldeko oi(h)anetan ɡatibatuɾik eromaɾa ekari s̻induten es̺klabua eremintaɾi ofis̻ioa eman s̻is̻uten eta kateak eɡiten ditus̻u labetik ateɾats̻en dus̻un burdin ɡoɾia na(h)ieɾan molda s̻enes̻ake es̻patak eɡin dits̻akes̻u s̻uɾe (h)eritarek kateak (h)auts̺ dits̻aten baina s̻uk es̺klabu (h)orek kateak eɡiten ditus̻u kate ɡe(h)iaɡo] The blacksmith slave Captive in the rainforests of the West they brought you to Rome, slave, they gave you the blacksmith work and you make chains.