Evolution of mammals

The mammaliaforms appeared during this period; their superior sense of smell, backed up by a large brain, facilitated entry into nocturnal niches with less exposure to archosaur predation.

The relatively new techniques of molecular phylogenetics have also shed light on some aspects of mammalian evolution by estimating the timing of important divergence points for modern species.

[citation needed] Although mammary glands are a signature feature of modern mammals, little is known about the evolution of lactation as these soft tissues are not often preserved in the fossil record.

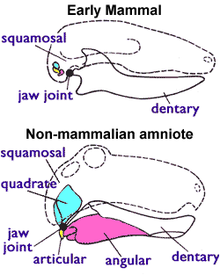

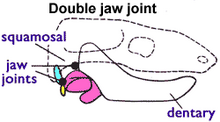

Other important research characteristics include the evolution of the middle ear bones, erect limb posture, a bony secondary palate, fur, hair, and warm-bloodedness.

[5] In a 1981 article, Kenneth A. Kermack and his co-authors argued for drawing the line between mammals and earlier synapsids at the point where the mammalian pattern of molar occlusion was being acquired and the dentary-squamosal joint had appeared.

The criterion chosen, they noted, is merely a matter of convenience; their choice was based on the fact that "the lower jaw is the most likely skeletal element of a Mesozoic mammal to be preserved.

[8] Amphibians Sauropsids (including dinosaurs) Cotylorhynchus Edaphosaurus Dimetrodon Mammals The first fully terrestrial vertebrates were reptilian amniotes — their eggs had internal membranes that allowed the developing embryo to breathe but kept water in.

[11][12] When referring to the ancestors and close relatives of mammals, paleontologists also use the following terms of convenience: Therapsids descended from sphenacodonts, a primitive synapsid, in the middle Permian, and took over from them as the dominant land vertebrates.

But dicynodonts were very different from modern herbivorous mammals, as their only teeth were a pair of fangs in the upper jaw (lost in some derived kannemeyeriiformes) and it is generally agreed that they had beaks like those of birds or ceratopsians.

[20] Numerous Changhsingian coprolites that possibly belong to therocephalians and indeterminate basal archosaurs (proterosuchids) contain elongated hollow structures that could be remains of hair.

Cynodonts' mammal-like features include further reduction in the number of bones in the lower jaw, a secondary bony palate, cheek teeth with a complex pattern in the crowns, and a brain which filled the endocranial cavity.

After the extinction event, the probainognathian cynodont group rapidly decreased in size (to 4–18 in (100–460 mm)) due to new competition with archosaurs and transitioned to nocturnality, evolving nocturnal features, pulmonary alveoli, bronchioles and a developed diaphragm for a larger surface area for breathing, enucleated erythrocytes, a large intestine which bears a true colon after the cecum, endothermy, a hairy, glandular and thermoregulatory skin (which releases sebum and sweat), and a 4-chambered heart to maintain their high metabolism, larger brains, and fully upright hindlimb (forelimbs remained semi sprawling, and became like that only later, in therians).

They appear to have evolved rapid growth and short lifespan, a life history trait also found in numerous modern small-bodied mammals.

[25] The catastrophic mass extinction at the end of the Permian, around 252 million years ago, killed off about 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species and the majority of land plants.

In an influential 1988 paper, Timothy Rowe advocated this restriction, arguing that "ancestry... provides the only means of properly defining taxa" and, in particular, that the divergence of the monotremes from the animals more closely related to marsupials and placentals "is of central interest to any study of Mammalia as a whole.

[46] Ausktribosphenidae † Monotremes Eutriconodonta † Multituberculates † Spalacotheroidea † Dryolestoidea † Marsupials Placentals Early amniotes had four opsins in the cones of their retinas to use for distinguishing colours: one sensitive to red, one to green, and two corresponding to different shades of blue.

[54] Recent analysis of Teinolophos, which lived somewhere between 121 and 112.5 million years ago, suggests that it was a "crown group" (advanced and relatively specialised) monotreme.

These features are not visible in fossils, and the main characteristics from paleontologists' point of view are:[52] Multituberculates (named for the multiple tubercles on their "molars") are often called the "rodents of the Mesozoic", but this is an example of convergent evolution rather than meaning that they are closely related to the Rodentia.

[58][59] Multituberculates are like undisputed crown mammals in that their jaw joints consist of only the dentary and squamosal bones-whereas the quadrate and articular bones are part of the middle ear; their teeth are differentiated, occlude, and have mammal-like cusps; they have a zygomatic arch; and the structure of the pelvis suggests that they gave birth to tiny helpless young, like modern marsupials.

[65] Didelphimorphia (common opossums of the Western Hemisphere) first appeared in the late Cretaceous and still have living representatives, probably because they are mostly semi-arboreal unspecialized omnivores.

[74] A recent analysis of phenomic characters, however, classified Eomaia as pre-eutherian and reported that the earliest clearly eutherian specimens came from Maelestes, dated to 91 million years ago.

Cingulata armadillos Pilosa anteaters, sloths golden moles, tenrecs, otter shrews elephant shrews aardvarks hyraxes elephants, mammoths, mastodons manatees, dugongs camels and llamas, pigs and peccaries, ruminants, whales and hippos shrews, hedgehogs, gymnures, moles and solenodons cats, dogs, bears, seals bats horses, rhinos, tapirs pangolins rabbits, hares, pikas mice and rats, cavys and porcupines, squirrels colugos tree shrews tarsiers, lemurs, monkeys, apes (including humans) Here are the most significant of the differences between this family tree and the one familiar to paleontologists: The grouping together of the Afrotheria has some geological justification: All surviving members of the Afrotheria originate from South American or (mainly) African lineages — even the Indian elephant, which diverged from an African lineage about 7.6 million years ago.

But some paleontologists, influenced by molecular phylogenetic studies, have used statistical methods to extrapolate backwards from fossils of members of modern groups and concluded that primates arose in the late Cretaceous.

[119] In fact, two of the suggestion's authors co-authored a later paper that reinterpreted the same features as evidence that Teinolophos was a full-fledged platypus, which means it would have had a mammalian jaw joint and middle ear.

Much of the argument is based on monotremes (egg-laying mammals):[120][121][122] Later research demonstrated that caseins already appeared in the common mammalian ancestor approximately 200–310 million years ago.

Ruben & Jones (2000) note that the Harderian glands, which secrete lipids for coating the fur, were present in the earliest mammals like Morganucodon, but were absent in near-mammalian therapsids like Thrinaxodon.

[146] "Warm-bloodedness" is a complex and rather ambiguous term, because it includes some or all of the following: Since scientists cannot know much about the internal mechanisms of extinct creatures, most discussion focuses on homeothermy and tachymetabolism.

However, it is generally agreed that endothermy first evolved in non-mammalian synapsids such as dicynodonts, which possess body proportions associated with heat retention,[147] high vascularised bones with Haversian canals,[148] and possibly hair.

But rudimentary ridges like those that support respiratory turbinates have been found in advanced Triassic cynodonts, such as Thrinaxodon and Diademodon, which suggests that they may have had fairly high metabolic rates.

Diaphragms are known in caseid pelycosaurs, indicating an early origin within synapsids, though they were still fairly inefficient and likely required support from other muscle groups and limb motion.