Evolution of sexual reproduction

In hermaphroditic reproduction, each of the two parent organisms required for the formation of a zygote can provide either the male or the female gamete, which leads to advantages in both size and genetic variance of a population.

[8] August Weismann picked up the thread in 1885, arguing that sex serves to generate genetic variation, as detailed in the majority of the explanations below.

[9] On the other hand, Charles Darwin (1809–1882) concluded that the effect of hybrid vigor (complementation) "is amply sufficient to account for the … genesis of the two sexes".

Since the emergence of the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 20th century, numerous biologists including W. D. Hamilton, Alexey Kondrashov, George C. Williams, Harris Bernstein, Carol Bernstein, Michael M. Cox, Frederic A. Hopf and Richard E. Michod – have suggested competing explanations for how a vast array of different living species maintain sexual reproduction.

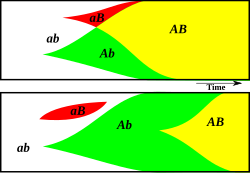

Lastly, sex creates new gene combinations that may be more fit than previously existing ones, or may simply lead to reduced competition among relatives.

Several studies have addressed counterarguments, and the question of whether this model is sufficiently robust to explain the predominance of sexual versus asexual reproduction remains.

One of the most widely discussed theories to explain the persistence of sex is that it is maintained to assist sexual individuals in resisting parasites, also known as the Red Queen Hypothesis.

In other words, like Lewis Carroll's Red Queen, sexual hosts are continually "running" (adapting) to "stay in one place" (resist parasites).

[24][25] Further evidence for the Red Queen hypothesis was provided by observing long-term dynamics and parasite coevolution in a "mixed" (sexual and asexual) population of snails (Potamopyrgus antipodarum).

Contrary to expectation based on the Red Queen hypothesis, they found that the prevalence, abundance and mean intensity of mites in sexual geckos was significantly higher than in asexuals sharing the same habitat.

In 2011, researchers used the microscopic roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans as a host and the pathogenic bacteria Serratia marcescens to generate a host-parasite coevolutionary system in a controlled environment, allowing them to conduct more than 70 evolution experiments testing the Red Queen Hypothesis.

[31] Critics of the Red Queen hypothesis question whether the constantly changing environment of hosts and parasites is sufficiently common to explain the evolution of sex.

Otto and Gerstein [33] further stated that "it seems doubtful to us that strong selection per gene is sufficiently commonplace for the Red Queen hypothesis to explain the ubiquity of sex".

Parker[34] reviewed numerous genetic studies on plant disease resistance and failed to uncover a single example consistent with the assumptions of the Red Queen hypothesis.

[35][page needed] In his manuscript, Smith further speculated on the impact of an asexual mutant arising in a sexual population, which suppresses meiosis and allows eggs to develop into offspring genetically identical to the mother by mitotic division.

[36][page needed] Thus, in this formulation, the principal cost of sex is that males and females must successfully copulate, which almost always involves expending energy to come together through time and space.

[38][39] As discussed in the earlier part of this article, sexual reproduction is conventionally explained as an adaptation for producing genetic variation through allelic recombination.

Genetic noise can occur as either physical damage to the genome (e.g. chemically altered bases of DNA or breaks in the chromosome) or replication errors (mutations).

However, outcrossing may be abandoned in favor of parthenogenesis or selfing (which retain the advantage of meiotic recombinational repair) under conditions in which the costs of mating are very high.

This lesser informational noise generates genetic variation, viewed by some as the major effect of sex, as discussed in the earlier parts of this article.

The genetic load of organisms and their populations will increase due to the addition of multiple deleterious mutations and decrease the overall reproductive success and fitness.

Thus, for instance, for the sexual species Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) and Neurospora crassa (fungus), the mutation rate per genome per replication are 0.0027 and 0.0030 respectively.

[62] The "libertine bubble theory" proposes that meiotic sex evolved in proto-eukaryotes to solve a problem that bacteria did not have, namely a large amount of DNA material, occurring in an archaic step of proto-cell formation and genetic exchanges.

So that, rather than providing selective advantages through reproduction, sex could be thought of as a series of separate events which combines step-by-step some very weak benefits of recombination, meiosis, gametogenesis and syngamy.

A harmful damage in a haploid individual, on the other hand, is more likely to become fixed (i.e. permanent), since any DNA repair mechanism would have no source from which to recover the original undamaged sequence.

[71] A similar origin of sexual reproduction is proposed to have evolved in ancient haloarchaea as a combination of two independent processes: jumping genes and plasmid swapping.

This model suggests that the nucleus originated when the lysogenic virus incorporated genetic material from the archaean and the bacterium and took over the role of information storage for the amalgam.

The presence of a lysogenic pox-like virus ancestor explains the development of meiotic division, an essential component of sexual reproduction.

[84] Meiotic division in the VE hypothesis arose because of the evolutionary pressures placed on the lysogenic virus as a result of its inability to enter into the lytic cycle.

Cavalier-Smith argues that both bouts of mechanical evolution were motivated by similar selective forces: the need for accurate DNA replication without loss of viability.