Stellar evolution

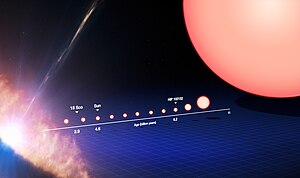

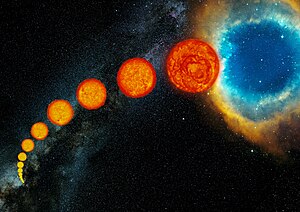

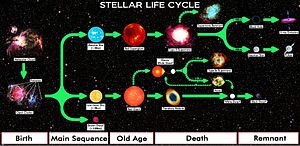

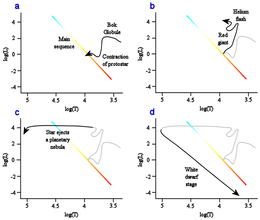

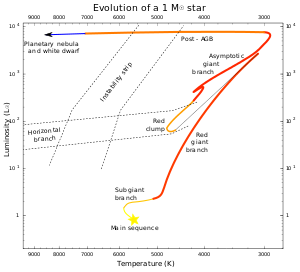

This process causes the star to gradually grow in size, passing through the subgiant stage until it reaches the red-giant phase.

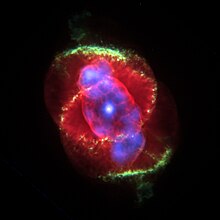

Once a star like the Sun has exhausted its nuclear fuel, its core collapses into a dense white dwarf and the outer layers are expelled as a planetary nebula.

Continuous accretion of gas, geometrical bending, and magnetic fields may control the detailed fragmentation manner of the filaments.

[4] A protostar continues to grow by accretion of gas and dust from the molecular cloud, becoming a pre-main-sequence star as it reaches its final mass.

Observations from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) have been especially important for unveiling numerous galactic protostars and their parent star clusters.

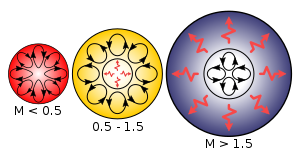

The International Astronomical Union defines brown dwarfs as stars massive enough to fuse deuterium at some point in their lives (13 Jupiter masses (MJ), 2.5 × 1028 kg, or 0.0125 M☉).

[7] Both types, deuterium-burning and not, shine dimly and fade away slowly, cooling gradually over hundreds of millions of years.

For a more-massive protostar, the core temperature will eventually reach 10 million kelvin, initiating the proton–proton chain reaction and allowing hydrogen to fuse, first to deuterium and then to helium.

In stars of slightly over 1 M☉ (2.0×1030 kg), the carbon–nitrogen–oxygen fusion reaction (CNO cycle) contributes a large portion of the energy generation.

The onset of nuclear fusion leads relatively quickly to a hydrostatic equilibrium in which energy released by the core maintains a high gas pressure, balancing the weight of the star's matter and preventing further gravitational collapse.

Depending on the mass of the helium core, this continues for several million to one or two billion years, with the star expanding and cooling at a similar or slightly lower luminosity to its main sequence state.

The effects of the CNO cycle appear at the surface during the first dredge-up, with lower 12C/13C ratios and altered proportions of carbon and nitrogen.

[13][15][16] Due to the expansion of the core, the hydrogen fusion in the overlying layers slows and total energy generation decreases.

The star contracts, although not all the way to the main sequence, and it migrates to the horizontal branch on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, gradually shrinking in radius and increasing its surface temperature.

The star follows the asymptotic giant branch on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, paralleling the original red-giant evolution, but with even faster energy generation (which lasts for a shorter time).

[19] Another well known class of asymptotic-giant-branch stars is the Mira variables, which pulsate with well-defined periods of tens to hundreds of days and large amplitudes up to about 10 magnitudes (in the visual, total luminosity changes by a much smaller amount).

They are not sufficiently massive to start full-scale carbon fusion, so they contract again, going through a period of post-asymptotic-giant-branch superwind to produce a planetary nebula with an extremely hot central star.

The gas builds up in an expanding shell called a circumstellar envelope and cools as it moves away from the star, allowing dust particles and molecules to form.

With the high infrared energy input from the central star, ideal conditions are formed in these circumstellar envelopes for maser excitation.

In massive stars, the core is already large enough at the onset of the hydrogen burning shell that helium ignition will occur before electron degeneracy pressure has a chance to become prevalent.

[citation needed] Extremely massive stars (more than approximately 40 M☉), which are very luminous and thus have very rapid stellar winds, lose mass so rapidly due to radiation pressure that they tend to strip off their own envelopes before they can expand to become red supergiants, and thus retain extremely high surface temperatures (and blue-white color) from their main-sequence time onwards.

Although lower-mass stars normally do not burn off their outer layers so rapidly, they can likewise avoid becoming red giants or red supergiants if they are in binary systems close enough so that the companion star strips off the envelope as it expands, or if they rotate rapidly enough so that convection extends all the way from the core to the surface, resulting in the absence of a separate core and envelope due to thorough mixing.

In sufficiently massive stars, the core reaches temperatures and densities high enough to fuse carbon and heavier elements via the alpha process.

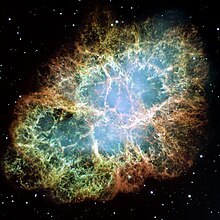

For a range of stars of approximately 8–12 M☉, this process is unstable and creates runaway fusion resulting in an electron capture supernova.

Because some of the rebounding matter is bombarded by the neutrons, some of its nuclei capture them, creating a spectrum of heavier-than-iron material including the radioactive elements up to (and likely beyond) uranium.

[30] In the past history of the universe, some stars were even larger than the largest that exists today, and they would immediately collapse into a black hole at the end of their lives, due to photodisintegration.

White dwarfs are stable because the inward pull of gravity is balanced by the degeneracy pressure of the star's electrons, a consequence of the Pauli exclusion principle.

Electron degeneracy pressure provides a rather soft limit against further compression; therefore, for a given chemical composition, white dwarfs of higher mass have a smaller volume.

Depending upon the chemical composition and pre-collapse temperature in the center, this will lead either to collapse into a neutron star or runaway ignition of carbon and oxygen.

According to classical general relativity, no matter or information can flow from the interior of a black hole to an outside observer, although quantum effects may allow deviations from this strict rule.