Evolution of the eye

In 1859, Charles Darwin himself wrote in his Origin of Species, that the evolution of the eye by natural selection seemed at first glance "absurd in the highest possible degree".

[3] However, he went on that despite the difficulty in imagining it, its evolution was perfectly feasible: ... if numerous gradations from a simple and imperfect eye to one complex and perfect can be shown to exist, each grade being useful to its possessor, as is certainly the case; if further, the eye ever varies and the variations be inherited, as is likewise certainly the case and if such variations should be useful to any animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, should not be considered as subversive of the theory.

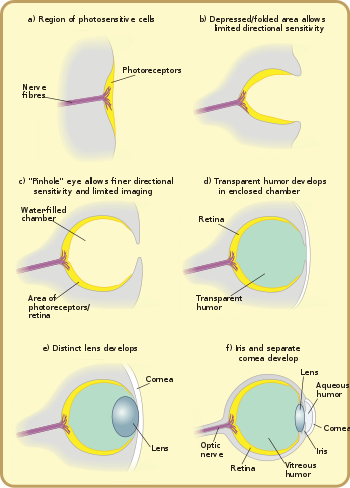

[3]He suggested a stepwise evolution from "an optic nerve merely coated with pigment, and without any other mechanism" to "a moderately high stage of perfection", and gave examples of existing intermediate.

[5] Nilsson and S. Pelger estimated in a classic paper that only a few hundred thousand generations are needed to evolve a complex eye in vertebrates.

How fast a circular patch of photoreceptor cells can evolve into a fully functional vertebrate eye has been estimated based on rates of mutation, relative advantage to the organism, and natural selection.

Opsins belong to a family of photo-sensitive proteins and fall into nine groups, which already existed in the urbilaterian, the last common ancestor of all bilaterally symmetrical animals.

[18][19][20] Such high-level genes are, by implication, much older than many of the structures that they control today; they must originally have served a different purpose, before they were co-opted for eye development.

[22] The earliest predecessors of the eye were photoreceptor proteins that sense light, found even in unicellular organisms, called "eyespots".

[23] Eyespots can sense only ambient brightness: they can distinguish light from dark, sufficient for photoperiodism and daily synchronization of circadian rhythms.

Visual pigments are located in the brains of more complex organisms, and are thought to have a role in synchronising spawning with lunar cycles.

By detecting the subtle changes in night-time illumination, organisms could synchronise the release of sperm and eggs to maximise the probability of fertilisation.

[24] At a cellular level, there appear to be two main types of eyes, one possessed by the protostomes (molluscs, annelid worms and arthropods), the other by the deuterostomes (chordates and echinoderms).

[24] The functional unit of the eye is the photoreceptor cell, which contains the opsin proteins and responds to light by initiating a nerve impulse.

[27] The actual derivation may be more complicated, as some microvilli contain traces of cilia – but other observations appear to support a fundamental difference between protostomes and deuterostomes.

These eyespots permit animals to gain only a basic sense of the direction and intensity of light, but not enough to discriminate an object from its surroundings.

However, this proto-eye is still much more useful for detecting the absence or presence of light than its direction; this gradually changes as the eye's pit deepens and the number of photoreceptive cells grows, allowing for increasingly precise visual information.

[21] During the Cambrian explosion, the development of the eye accelerated rapidly, with radical improvements in image-processing and detection of light direction.

[30] After the photosensitive cell region invaginated, there came a point when reducing the width of the light opening became more efficient at increasing visual resolution than continued deepening of the cup.

[12] By reducing the size of the opening, organisms achieved true imaging, allowing for fine directional sensing and even some shape-sensing.

Lacking a cornea or lens, they provide poor resolution and dim imaging, but are still, for the purpose of vision, a major improvement over the early eyepatches.

The chamber contents, now segregated, could slowly specialize into a transparent humour, for optimizations such as colour filtering, higher refractive index, blocking of ultraviolet radiation, or the ability to operate in and out of water.

These crystallins are special because they have the unique characteristics required for transparency and function in the lens such as tight packing, resistance to crystallization, and extreme longevity, as they must survive for the entirety of the organism's life.

[42] A gap between tissue layers naturally forms a biconvex shape, which is optically and mechanically ideal for substances of normal[clarification needed] refractive index.

[29] This may have happened at any of the early stages of the eye's evolution, and may have disappeared and reevolved as relative selective pressures on the lineage varied.

Additionally, cuttlefish are capable of perceiving the polarization of light with high visual fidelity, although they appear to lack any significant capacity for color differentiation.

Because of the marginal reflective interference of polarized light, it is often used for orientation and navigation, as well as distinguishing concealed objects, such as disguised prey.

Another mechanism regulates focusing chemically and independently of these two, by controlling growth of the eye and maintaining focal length.

When using a circular form, the pupil will constrict under bright light, increasing the f-number, and will dilate when dark in order to decrease the depth of focus.

Prey animals' eyes tend to be on the side of the head giving a wide field of view to detect predators from any direction.