Evolutionary approaches to depression

In contrast to these patterns, prevalence of clinical depression is high in all age categories, including otherwise healthy adolescents and young adults.

It motivates them to cease activities that led to the costly situation, if possible, and it causes him or her to learn to avoid similar circumstances in the future.

Alongside the absence of pleasure, other noticeable changes include psychomotor retardation, disrupted patterns of sleeping and feeding, a loss of sex drive and motivation—which are all also characteristics of the body's reaction to actual physical pain.

[14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] The behavioral shutdown model states that if an organism faces more risk or expenditure than reward from activities, the best evolutionary strategy may be to withdraw from them.

Negative emotions like disappointment, sadness, grief, fear, anxiety, anger, and guilt are described as "evolved strategies that allow for the identification and avoidance of specific problems, especially in the social domain."

Depression is characteristically associated with anhedonia and lack of energy, and those experiencing it are risk-aversive and perceive more negative and pessimistic outcomes because they are focused on preventing further loss.

That is to say, if uncontrollable and unstoppable stressors are repeated for long enough, a rat subject will adopt a learned helplessness, which shares a number of behavioral and psychological features with human depression.

From an evolutionary perspective, learned helplessness also allows a conservation of energy for an extended period of time should people find themselves in a predicament that is outside of their control, such as an illness or a dry season.

[25] This hypothesis suggests that depression is an adaptation that causes the affected individual to concentrate his or her attention and focus on a complex problem in order to analyze and solve it.

Feelings of regret associated with depression also cause individuals to reflect and analyze past events in order to determine why they happened and how they could have been prevented.

The ability to feel pain and experience depression, are adaptive defense mechanisms,[30] but when they are "too easily triggered, too intense, or long lasting", they can become "dysregulated".

The fitness benefits of forming cooperative bonds with others have long been recognised—during the Pleistocene period, for instance, social ties were vital for food foraging and finding protection from predators.

[12] As such, depression is seen to represent an adaptive, risk-averse response to the threat of exclusion from social relationships that would have had a critical impact on the survival and reproductive success of our ancestors.

Multiple lines of evidence on the mechanisms and phenomenology of depression suggest that mild to moderate (or "normative") depressed states preserve an individual's inclusion in key social contexts via three intersecting features: a cognitive sensitivity to social risks and situations (e.g., "depressive realism"); it inhibits confident and competitive behaviours that are likely to put the individual at further risk of conflict or exclusion (as indicated by symptoms such as low self-esteem and social withdrawal); and it results in signalling behaviours directed toward significant others to elicit more of their support (e.g., the so-called "cry for help").

[12][33] According to this view, the severe cases of depression captured by clinical diagnoses reflect the maladaptive, dysregulation of this mechanism, which may partly be due to the uncertainty and competitiveness of the modern, globalised world.

[34] In the wake of a serious negative life event, such as those that have been implicated in depression (e.g., death, divorce), "cheap" signals of need, such as crying, might not be believed when social partners have conflicts of interest.

Such individuals who have many conflicts with their social partners, in contrast, are predicted to experience depression—a means, in part, to credibly signal need to others who might be skeptical that the need is genuine.

[35][36] Depression is not only costly to the affected person, it also imposes a significant burden on family, friends, and society at large—yet another reason it is thought to be pathological.

Thus, not only do the symptoms of major depression serve as costly and therefore honest signals of need, they also compel reluctant social partners to respond to that need in order to prevent their own fitness from being reduced.

Finally, for social partners who find it uneconomical to respond helpfully to an honest signal of need, the same depressive symptoms also have the potential to extort relevant concessions and compromises.

In animal models, the prolonged overreaction of the immune system, in response to the strain of chronic disease, results in an increased production of cytokines (a diverse group of hormonal regulators and signaling molecules).

The overproduction of these cytokines, beyond optimal levels due to the repeated demands of dealing with a chronic disease, may result in clinical depression and its accompanying behavioral manifestations that promote extreme energy reservation.

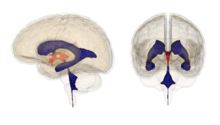

[43] The third ventricle hypothesis of depression proposes that the behavioural cluster associated with depression (hunched posture, avoidance of eye contact, reduced appetites for food and sex plus social withdrawal and sleep disturbance) serves to reduce an individual's attack-provoking stimuli within the context of a chronically hostile social environment.

[49] Some psychiatrists raise the concern that evolutionary psychologists seek to explain hidden adaptive advantages without engaging the rigorous empirical testing required to back up such claims.

[49][50] While there is strong research to suggest a genetic link to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, there is significant debate within clinical psychology about the relative influence and the mediating role of cultural or environmental factors.

[51] For example, epidemiological research suggests that different cultural groups may have divergent rates of diagnosis, symptomatology, and expression of mental illnesses.