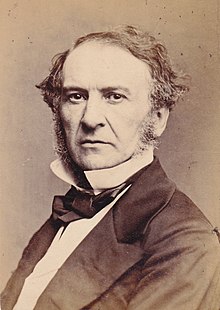

William Ewart Gladstone

[1][2] After the 1880 general election, Gladstone formed his second ministry (1880–1885), which saw the passage of the Third Reform Act as well as crises in Egypt (culminating in the Fall of Khartoum) and Ireland, where his government passed repressive measures but also improved the legal rights of Irish tenant farmers.

One of his earliest childhood memories was being made to stand on a table and say "Ladies and gentlemen" to the assembled audience, probably at a gathering to promote the election of George Canning as MP for Liverpool in 1812.

[16] After new bills to protect child workers were proposed following the publication of the Sadler report, he voted against the 1833 Factory Acts that would regulate the hours of work and welfare of minors employed in cotton mills.

Gladstone, who had previously argued in a book that a Protestant country should not pay money to other churches, nevertheless supported the increase in the Maynooth grant and voted for it in Commons, but resigned rather than face charges that he had compromised his principles to remain in office.

[46] The contemporary diarist Charles Greville wrote of Gladstone's speech: ... by universal consent it was one of the grandest displays and most able financial statement that ever was heard in the House of Commons; a great scheme, boldly, skilfully, and honestly devised, disdaining popular clamour and pressure from without, and the execution of it absolute perfection.

Eventually, he became notorious for this activity, prompting Lord Randolph Churchill to observe: For the purposes of recreation he has selected the felling of trees; and we may usefully remark that his amusements, like his politics, are essentially destructive.

[75][76] Gladstone was forced to clarify in the press that his comments in Newcastle had not been intended to signal a change in Government policy, but to express his belief that the North's efforts to defeat the South would fail, due to the strength of Southern resistance.

The Local Government Board Act 1871 put the supervision of the Poor Law under the Local Government Board (headed by G. J. Goschen) and Gladstone's "administration could claim spectacular success in enforcing a dramatic reduction in supposedly sentimental and unsystematic outdoor poor relief, and in making, in co-operation with the Charity Organization Society (1869), the most sustained attempt of the century to impose upon the working classes the Victorian values of providence, self-reliance, foresight, and self-discipline".

[92] At a speech at Blackheath on 28 October 1871, he warned his constituents against these social reformers: ... they are not your friends, but they are your enemies in fact, though not in intention, who teach you to look to the Legislature for the radical removal of the evils that afflict human life.

And those who ... promise to the dwellers in towns that every one of them shall have a house and garden in free air, with ample space; those who tell you that there shall be markets for selling at wholesale prices retail quantities – I won't say are impostors, because I have no doubt they are sincere; but I will say they are quacks (cheers); they are deluded and beguiled by a spurious philanthropy, and when they ought to give you substantial, even if they are humble and modest boons, they are endeavouring, perhaps without their own consciousness, to delude you with fanaticism, and offering to you a fruit which, when you attempt to taste it, will prove to be but ashes in your mouths.

[b] Gladstone's proposals went some way to meet working-class demands, such as the realisation of the free breakfast table through repealing duties on tea and sugar, and reform of local taxation which was increasing for the poorer ratepayers.

More important, he was strongly opposed to the authoritarianism of its pope and bishops, its profound public opposition to liberalism, and its supposed refusal to distinguish between secular allegiance on the one hand and spiritual obedience on the other.

Cardinal Manning denied that the council had changed the relation of Catholics to their civil governments, and Archbishop James Roosevelt Bayley, in a letter which was obtained by the New York Herald and published without Bayley's express permission, called Gladstone's declaration "a shameful calumny" and attributed his "monomania" to the "political hari-kari" he had committed by dissolving Parliament, accusing him of "putting on 'the cap and bells' and attempting to play the part of Lord George Gordon" in order to restore his political fortunes.

[109] Lord Kilbracken, one of Gladstone's secretaries, commented: The Liberal doctrines of that time, with their violent anti-socialist spirit and their strong insistence on the gospel of thrift, self-help, settlement of wages by the higgling of the market, and non-interference by the State....

[114]The historian Geoffrey Alderman has described Gladstone as "unleashing the full fury of his oratorical powers against Jews and Jewish influence" during the Bulgarian Crisis (1885–88), telling a journalist in 1876 that: "I deeply deplore the manner in which, what I may call Judaic sympathies, beyond as well as within the circle of professed Judaism, are now acting on the question of the East".

[118][119] Paul Hayes says it "provides one of the most intriguing and perplexing tales of muddle and incompetence in foreign affairs, unsurpassed in modern political history until the days of Grey and, later, Neville Chamberlain.

Instead, they saw the urgent necessity to act to protect the Suez Canal in the face of what appeared to be a radical collapse of law and order, and a nationalist revolt focused on expelling the Europeans, regardless of the damage it would do to international trade and the British Empire.

Critics such as Cain and Hopkins have stressed the need to protect large sums invested by British financiers and Egyptian bonds while downplaying the risk to the viability of the Suez Canal.

In a letter to Lord Acton on 11 February 1885, Gladstone criticised Tory Democracy as "demagogism" that "put down pacific, law-respecting, economic elements that ennobled the old Conservatism" but "still, in secret, as obstinately attached as ever to the evil principle of class interests".

Gladstone, says his biographer, "totally rejected the widespread English view that the Irish had no taste for justice, common sense, moderation or national prosperity and looked only to perpetual strife and dissension".

[141] On 11 December 1891 Gladstone said that: "It is a lamentable fact if, in the midst of our civilisation, and at the close of the nineteenth century, the workhouse is all that can be offered to the industrious labourer at the end of a long and honourable life.

Gladstone wrote to Herbert Spencer, who contributed the introduction to a collection of anti-socialist essays (A Plea for Liberty, 1891), that "I ask to make reserves, and of one passage, which will be easily guessed, I am unable even to perceive the relevancy.

[151] In January 1894, Gladstone wrote that he would not "break to pieces the continuous action of my political life, nor trample on the tradition received from every colleague who has ever been my teacher" by supporting naval rearmament.

On 2 January 1897, Gladstone wrote to Francis Hirst on being unable to draft a preface to a book on liberalism: "I venture on assuring you that I regard the design formed by you and your friends with sincere interest, and in particular wish well to all the efforts you may make on behalf of individual freedom and independence as opposed to what is termed Collectivism".

[177] Initially a disciple of High Toryism, Gladstone's maiden speech as a young Tory was a defence of the rights of West Indian sugar plantation magnates (slave owners) among whom his father was prominent.

[187] Looking back late in life, Gladstone named the abolition of slavery as one of ten great achievements of the previous sixty years where the masses had been right and the upper classes had been wrong.

[194] Historian Walter L. Arnstein concludes: Notable as the Gladstonian reforms had been, they had almost all remained within the 19th-century Liberal tradition of gradually removing the religious, economic and political barriers that prevented men of varied creeds and classes from exercising their individual talents in order to improve themselves and their society.

As the third quarter of the century drew to a close, the essential bastions of Victorianism still held firm: respectability; a government of aristocrats and gentlemen now influenced not only by middle-class merchants and manufacturers but also by industrious working people: a prosperity that seemed to rest largely on the tenets of laissez-faire economics; and a Britannia that ruled the waves and many a dominion beyond.

[232] Portrayals include: ... there was one man who not only united high ability with unparalleled opportunity but also knew how to turn budgets into political triumphs and who stands in history as the greatest English financier of economic liberalism, Gladstone.

The greatest feature of Gladstonian finance ... was that it expressed with ideal adequacy both the whole civilisation and the needs of the time, ex visu of the conditions of the country to which it was to apply; or, to put it slightly differently, that it translated a social, political, and economic vision, which was comprehensive as well as historically correct, into the clauses of a set of co-ordinated fiscal measures.