Execution of Charles I

Charles I, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, was executed on Tuesday, 30 January 1649[b] outside the Banqueting House on Whitehall, London.

The execution was the culmination of political and military conflicts between the royalists and the parliamentarians in England during the English Civil War, leading to the capture and trial of Charles.

On Saturday 27 January 1649, the parliamentarian High Court of Justice had declared Charles guilty of attempting to "uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people" and sentenced him to death by beheading.

[2] Charles spent his last few days in St James's Palace, accompanied by his most loyal subjects and visited by his family.

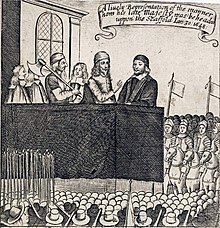

Charles stepped onto the scaffold and gave his last speech, declaring his innocence of the crimes of which parliament had accused him, and claiming himself a "martyr of the people".

The crowd could not hear the speech, owing to the many parliamentarian guards blocking the scaffold, but Charles's companion, Bishop William Juxon, recorded it in shorthand.

Charles gave a few last words to Juxon, claiming an "incorruptible crown" for himself in Heaven, and put his head on the block.

[23] At noon, Charles drank a glass of claret wine and ate a piece of bread, reportedly having been persuaded to this effect by Juxon.

[42] The executioner dropped the king's head into the crowd and the soldiers swarmed around it, dipping their handkerchiefs in his blood and cutting off locks of his hair.

[44] The identities of the executioner of Charles I and his assistant were never revealed to the public, with crude face masks and wigs hiding them at the execution,[46] and they were probably known only to Oliver Cromwell and a few of his colleagues.

[57] Despite this, Brandon denied being the executioner throughout his life, and a contemporary letter claims that he refused a parliamentarian offer of £200 to perform the execution.

[59][60] Of the other suggested candidates: Peter had prominently advocated for Charles's death but was absent from his execution, though he was reported to have been kept at home through illness.

[64] That thence the Royal actor borne The tragic scaffold might adorn: While round the armèd bands Did clap their bloody hands.

[68] Even Charles showed planning for his future martyrdom: apparently delighted that the biblical passage to be read upon the day of his execution was Matthew's account of the Crucifixion.

It aggravated the fervor of the royalists in the wake of Charles's execution and their high praise led to the wide circulation of the book; some sections even put into verse and music for the uneducated and illiterate of the population.

[84] Most European nations had their own troubles occupying their minds, such as negotiating the terms of the recently signed Peace of Westphalia, and the regicide was treated with what Richard Bonney described as a "half-hearted irrelevance".

[86] One notable exception was the Russian Tsar Alexis, who broke off diplomatic relations with England and accepted royalist refugees in Moscow.

[87] News of the execution of Charles I travelled slowly to the colonies; on 26 May Roger Williams of Rhode Island reported that "the King and many great Lords and Parliament men are beheaded," and on 3 June Adam Winthrop reported from Boston that "heer is now a London shipp come in, that bringeth the newes that the King is beheaded."

However, the initial content of the discussion from letters and diaries remains unclear: Not until God seemed to signify his approval of the regicide by showering victories on the Commonwealth's armies did public statements of colonial views begin to appear.

When Cromwell led the English forces to victory over Charles II and his Scottish supporters at Dunbar in September 1650, the churches of New England celebrated with a day of thanksgiving.

[93] Much Restoration historiography of the Civil War emphasised the regicide as a grand and theatrical tragedy, depicting the last days of Charles's life in a hagiographical fashion.

[97] To delegitimise this cult, later Whigs spread the view of Charles as a tyrant, and his execution as a step towards constitutional government in Britain.

In opposition, British Tory literary and political figures, including Isaac D'Israeli and Walter Scott, attempted to rejuvenate the cult with romanticised tales of Charles's execution—emphasising the same tropes of martyrdom the royalists had done before them.

Personal rulers might indeed reappear, and Parliament had not yet so displayed its superiority as a governing power to make Englishmen anxious to dispense with monarchy in some form or other.

Insecurity of tenure would make it impossible for future rulers long to set public opinion at naught, as Charles had done.

Films and television have exploited the dramatic tension and shock of the execution for many purposes: from comedy as in Blackadder: The Cavalier Years, to period drama as in To Kill a King.