Existentialism

Existentialism is a family of philosophical views and inquiry that study existence from the individual's perspective and explore the human struggle to lead an authentic life despite the apparent absurdity or incomprehensibility of the universe.

[5][6][7] Among the 19th-century figures now associated with existentialism are philosophers Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche, as well as novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, all of whom critiqued rationalism and concerned themselves with the problem of meaning.

The word existentialism, however, was not coined until the mid-20th century, during which it became most associated with contemporaneous philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre, Martin Heidegger, Simone de Beauvoir, Karl Jaspers, Gabriel Marcel, Paul Tillich, and more controversially Albert Camus.

Some scholars argue that the term should be used to refer only to the cultural movement in Europe in the 1940s and 1950s associated with the works of the philosophers Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Albert Camus.

[29][30] Simone de Beauvoir, on the other hand, holds that there are various factors, grouped together under the term sedimentation, that offer resistance to attempts to change our direction in life.

Many of the literary works of Kierkegaard, Beckett, Kafka, Dostoevsky, Ionesco, Miguel de Unamuno, Luigi Pirandello,[36][37][38][39] Sartre, Joseph Heller, and Camus contain descriptions of people who encounter the absurdity of the world.

Another characteristic feature of the Look is that no Other really needs to have been there: It is possible that the creaking floorboard was simply the movement of an old house; the Look is not some kind of mystical telepathic experience of the actual way the Other sees one (there may have been someone there, but he could have not noticed that person).

The rejection of reason as the source of meaning is a common theme of existentialist thought, as is the focus on the anxiety and dread that we feel in the face of our own radical free will and our awareness of death.

Existentialist philosophers often stress the importance of angst as signifying the absolute lack of any objective ground for action, a move that is often reduced to moral or existential nihilism.

"[63] Precursors to existentialism can also be identified in the works of Iranian Muslim philosopher Mulla Sadra (c. 1571–1635), who would posit that "existence precedes essence" becoming the principle expositor of the School of Isfahan, which is described as "alive and active".

Yet he continues to imply that a leap of faith is a possible means for an individual to reach a higher stage of existence that transcends and contains both an aesthetic and ethical value of life.

He retained a sense of the tragic, even absurd nature of the quest, symbolized by his enduring interest in the eponymous character from the Miguel de Cervantes novel Don Quixote.

A novelist, poet and dramatist as well as philosophy professor at the University of Salamanca, Unamuno wrote a short story about a priest's crisis of faith, Saint Manuel the Good, Martyr, which has been collected in anthologies of existentialist fiction.

Gabriel Marcel, long before coining the term "existentialism", introduced important existentialist themes to a French audience in his early essay "Existence and Objectivity" (1925) and in his Metaphysical Journal (1927).

Harmony, for Marcel, was to be sought through "secondary reflection", a "dialogical" rather than "dialectical" approach to the world, characterized by "wonder and astonishment" and open to the "presence" of other people and of God rather than merely to "information" about them.

Following the Second World War, existentialism became a well-known and significant philosophical and cultural movement, mainly through the public prominence of two French writers, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, who wrote best-selling novels, plays and widely read journalism as well as theoretical texts.

[83] Sartre had traveled to Germany in 1930 to study the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger,[87] and he included critical comments on their work in his major treatise Being and Nothingness.

[88] The lectures were highly influential; members of the audience included not only Sartre and Merleau-Ponty, but Raymond Queneau, Georges Bataille, Louis Althusser, André Breton, and Jacques Lacan.

Although often overlooked due to her relationship with Sartre,[95] de Beauvoir integrated existentialism with other forms of thinking such as feminism, unheard of at the time, resulting in alienation from fellow writers such as Camus.

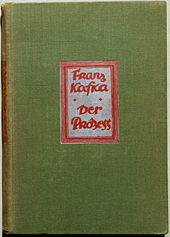

[98] Orson Welles's 1962 film The Trial, based upon Franz Kafka's book of the same name (Der Prozeß), is characteristic of both existentialist and absurdist themes in its depiction of a man (Joseph K.) arrested for a crime for which the charges are neither revealed to him nor to the reader.

Existential themes of individuality, consciousness, freedom, choice, and responsibility are heavily relied upon throughout the entire series, particularly through the philosophies of Jean-Paul Sartre and Søren Kierkegaard.

[100] Notable directors known for their existentialist films include Ingmar Bergman, Bela Tarr, Robert Bresson, Jean-Pierre Melville, François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, Akira Kurosawa, Terrence Malick, Stanley Kubrick, Andrei Tarkovsky, Éric Rohmer, Wes Anderson, Woody Allen, and Christopher Nolan.

[102] Similarly, in Kurosawa's Red Beard, the protagonist's experiences as an intern in a rural health clinic in Japan lead him to an existential crisis whereby he questions his reason for being.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline's Journey to the End of the Night (Voyage au bout de la nuit, 1932) celebrated by both Sartre and Beauvoir, contained many of the themes that would be found in later existential literature, and is in some ways, the proto-existential novel.

[105] Between 1900 and 1960, other authors such as Albert Camus, Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke, T. S. Eliot, Yukio Mishima, Hermann Hesse, Luigi Pirandello,[36][37][39][106][107][108] Ralph Ellison,[109][110][111][112] and Jack Kerouac composed literature or poetry that contained, to varying degrees, elements of existential or proto-existential thought.

[113] Sartre wrote No Exit in 1944, an existentialist play originally published in French as Huis Clos (meaning In Camera or "behind closed doors"), which is the source of the popular quote, "Hell is other people."

To occupy themselves, the men eat, sleep, talk, argue, sing, play games, exercise, swap hats, and contemplate suicide—anything "to hold the terrible silence at bay".

[119] Classical and contemporary thinkers include C.L.R James, Frederick Douglass, W.E.B DuBois, Frantz Fanon, Angela Davis, Cornel West, Naomi Zack, bell hooks, Stuart Hall, Lewis Gordon, and Audre Lorde.

Yalom states that Aside from their reaction against Freud's mechanistic, deterministic model of the mind and their assumption of a phenomenological approach in therapy, the existentialist analysts have little in common and have never been regarded as a cohesive ideological school.

These thinkers—who include Ludwig Binswanger, Medard Boss, Eugène Minkowski, V. E. Gebsattel, Roland Kuhn, G. Caruso, F. T. Buytendijk, G. Bally, and Victor Frankl—were almost entirely unknown to the American psychotherapeutic community until Rollo May's highly influential 1958 book Existence—and especially his introductory essay—introduced their work into this country.