Experimental evolution

[2] Other evolutionary forces outside of mutation and natural selection can also play a role or be incorporated into experimental evolution studies, such as genetic drift and gene flow.

[1][4][5] Polymorphic populations of asexual or sexual yeast,[2] and multicellular eukaryotes like Drosophila, can adapt to new environments through allele frequency change in standing genetic variation.

Selective breeding of plants and animals has led to varieties that differ dramatically from their original wild-type ancestors.

The power of human breeding to create varieties with extreme differences from a single species was already recognized by Charles Darwin.

Altogether at least a score of pigeons might be chosen, which if shown to an ornithologist, and he were told that they were wild birds, would certainly, I think, be ranked by him as well-defined species.

Moreover, I do not believe that any ornithologist would place the English carrier, the short-faced tumbler, the runt, the barb, pouter, and fantail in the same genus; more especially as in each of these breeds several truly-inherited sub-breeds, or species as he might have called them, could be shown him.

(...) I am fully convinced that the common opinion of naturalists is correct, namely, that all have descended from the rock-pigeon (Columba livia), including under this term several geographical races or sub-species, which differ from each other in the most trifling respects.One of the first to carry out a controlled evolution experiment was William Dallinger.

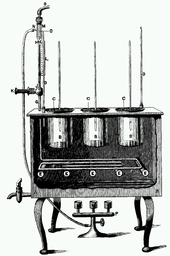

In the late 19th century, he cultivated small unicellular organisms in a custom-built incubator over a time period of seven years (1880–1886).

[11][12] From the 1880s to 1980, experimental evolution was intermittently practiced by a variety of evolutionary biologists, including the highly influential Theodosius Dobzhansky.

[23] One of the first of a new wave of experiments using this strategy was the laboratory "evolutionary radiation" of Drosophila melanogaster populations that Michael R. Rose started in February, 1980.

[26] Subsequently, Thomas Turner coined the term Evolve and Resequence (E&R)[10] and several studies used E&R approach with mixed success.

Much recently the experimental evolution in flies have taken the course to address the molecular mechanisms[32][33] and in doing so it might pave way to understand physiology of an organism better and thus redefine disease therapeutics.

On February 24, 1988, Lenski started growing twelve lineages of E. coli under identical growth conditions.

[43] In 1993, Theodore Garland, Jr. and colleagues started a long-term experiment that involves selective breeding of mice for high voluntary activity levels on running wheels.

[46] The HR mice have an elevated endurance running ability [47] and maximal aerobic capacity [48] when tested on a motorized treadmill.

[49] The High Runner lines have been proposed as a model to study human attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and administration of Ritalin reduces their wheel running approximately to the levels of control mice.

[50] In 2005 Paweł Koteja with Edyta Sadowska and colleagues from the Jagiellonian University (Poland) started a multidirectional selection on a non-laboratory rodent, the bank vole Myodes (= Clethrionomys) glareolus.

[51] The voles are selected for three distinct traits, which played important roles in the adaptive radiation of terrestrial vertebrates: high maximum rate of aerobic metabolism, predatory propensity, and herbivorous capability.

Although the selection protocol does not impose a thermoregulatory burden, both the basal metabolic rate and thermogenic capacity increased in the Aerobic lines.

Synthetic biological circuits inserted into the genome of Escherichia coli[56] or the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae[57] degrade (lose function) during laboratory evolution.