Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950)

[3] Joseph Stalin, in concert with other Communist leaders, planned to expel all ethnic Germans from east of the Oder and from lands which from May 1945 fell inside the Soviet occupation zones.

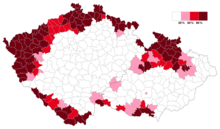

The areas affected included the former eastern territories of Germany, which were annexed by Poland,[8][9] as well as the Soviet Union after the war and Germans who were living within the borders of the pre-war Second Polish Republic, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, and the Baltic states.

Within these areas of diversity, including the major cities of Central and Eastern Europe, people in various ethnic groups had interacted every day for centuries, while not always harmoniously, on every civic and economic level.

It was also the first modern European state to propose population transfers as a means of solving "nationality conflicts", intending the removal of Poles and Jews from the projected post–World War I "Polish Border Strip" and its resettlement with Christian ethnic Germans.

The major motivations revealed were: The creation of ethnically homogeneous nation states in Central and Eastern Europe[54] was presented as the key reason for the official decisions of the Potsdam and previous Allied conferences as well as the resulting expulsions.

[62] In Poland and Czechoslovakia, newspapers,[76] leaflets and politicians across the political spectrum,[76][77] which narrowed during the post-war Communist take-over,[77] asked for retribution for wartime German activities.

"[76] In Poland, which had suffered the loss of six million citizens, including its elite and almost its entire Jewish population due to Lebensraum and the Holocaust, most Germans were seen as Nazi-perpetrators who could now finally be collectively punished for their past deeds.

[80][84] Between 23 January and 5 May 1945, up to 250,000 Germans, primarily from East Prussia, Pomerania, and the Baltic states, were evacuated to Nazi-occupied Denmark,[89][90] based on an order issued by Hitler on 4 February 1945.

[100] The agreement further called for equal distribution of the transferred Germans for resettlement among American, British, French and Soviet occupation zones comprising post–World War II Germany.

During and after the war, 2,208,000 Poles fled or were expelled from the former eastern Polish regions that were merged to the USSR after the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland; 1,652,000 of these refugees were resettled in the former German territories.

[117] However, in 1995, research by a joint German and Czech commission of historians found that the previous demographic estimates of 220,000 to 270,000 deaths to be overstated and based on faulty information.

[125] Data from the Russian archives, which were based on an actual enumeration, put the number of ethnic Germans registered by the Soviets in Hungary at 50,292 civilians, of whom 31,923 were deported to the USSR for reparation labor implementing Order 7161.

[155][156] At the Potsdam Conference (17 July – 2 August 1945), the territory to the east of the Oder–Neisse line was assigned to Polish and Soviet Union administration pending the final peace treaty.

[159] The remaining population faced theft and looting, and also in some instances rape and murder by the criminal elements, crimes that were rarely prevented nor prosecuted by the Polish Militia Forces and newly installed communist judiciary.

[161] Polish historians Witold Sienkiewicz and Grzegorz Hryciuk maintain that the internment:resulted in numerous deaths, which cannot be accurately determined because of lack of statistics or falsification.

[172] Tomasz Kamusella cites estimates of 7 million expelled in total during both the "wild" and "legal" expulsions from the recovered territories from 1945 to 1948, plus an additional 700,000 from areas of pre-war Poland.

[178] Data from the Russian archives which were based on an actual enumeration put the number of ethnic Germans registered by the Soviets in Romania at 421,846 civilians, of whom 67,332 were deported to the USSR for reparation labour, where 9% (6,260) died.

[126] The roughly 400,000 ethnic Germans who remained in Romania were treated as guilty of collaboration with Nazi Germany [citation needed] and were deprived of their civil liberties and property.

[citation needed] In 1948, Romania began a gradual rehabilitation of the ethnic Germans: they were not expelled, and the communist regime gave them the status of a national minority, the only Eastern Bloc country to do so.

[192] The special "German settlements" in the post-war Soviet Union were controlled by the Internal Affairs Commissioner, and the inhabitants had to perform forced labor until the end of 1955.

Many Germans were evacuated from East Prussia and the Memel territory by Nazi authorities during Operation Hannibal or fled in panic as the Red Army approached.

[206][207] Fearing a Nazi Fifth Column, between 1941 and 1945 the US government facilitated the expulsion of 4,058 German citizens from 15 Latin American countries to internment camps in Texas and Louisiana.

[250] On 29 November 2006, State Secretary in the German Federal Ministry of the Interior, Christoph Bergner, outlined the stance of the respective governmental institutions on Deutschlandfunk (a public-broadcasting radio station in Germany) saying that the numbers presented by the German government and others are not contradictory to the numbers cited by Haar and that the below 600,000 estimate comprises the deaths directly caused by atrocities during the expulsion measures and thus only includes people who were raped, beaten, or else killed on the spot, while the above two million estimate includes people who on their way to postwar Germany died of epidemics, hunger, cold, air raids and the like.

[262] Britain and the US protested against the actions of the French military government but had no means to force France to bear the consequences of the expulsion policy agreed upon by American, British and Soviet leaders in Potsdam.

[266] The Soviets, who encouraged and partly carried out the expulsions, offered little cooperation with humanitarian efforts, thereby requiring the Americans and British to absorb the expellees in their zones of occupation.

Consequently, Britain had to incur additional debt to the US, and the US had to spend more for the survival of its zone, while the Soviets gained applause among Eastern Europeans—many of whom were impoverished by the war and German occupation—who plundered the belongings of expellees, often before they were actually expelled.

[citation needed] This effort was led by the Sonne Commission, a 14-member body consisting of nine Americans and five Germans within the Economic Cooperation Administration which was tasked with devising strategies to solve the refugee crisis.

[303] East Germany sought to avoid alienating the Soviet Union and its neighbours; the Polish and Czechoslovakian governments characterised the expulsions as "a just punishment for Nazi crimes".

[318] The former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights José Ayala Lasso of Ecuador endorsed the establishment of the Centre Against Expulsions in Berlin.

[332] Five years later, in 2014, the government of Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka decided that the exemption was "no longer relevant" and that the withdrawal of the opt-out "would help improve Prague's position with regard to other EU international agreements.