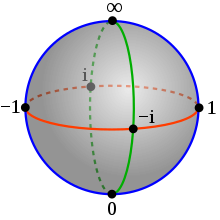

Riemann sphere

As with any compact Riemann surface, the sphere may also be viewed as a projective algebraic curve, making it a fundamental example in algebraic geometry.

It also finds utility in other disciplines that depend on analysis and geometry, such as the Bloch sphere of quantum mechanics and in other branches of physics.

have no common factor) can be extended to a continuous function on the Riemann sphere.

Since the transition maps are holomorphic, they define a complex manifold, called the Riemann sphere.

Intuitively, the transition maps indicate how to glue two planes together to form the Riemann sphere.

Topologically, the resulting space is the one-point compactification of a plane into the sphere.

The Riemann sphere can also be defined as the complex projective line.

The points of the complex projective line can be defined as equivalence classes of non-null vectors in the complex vector space

[3] This treatment of the Riemann sphere connects most readily to projective geometry.

It is also convenient for studying the sphere's automorphisms, later in this article.

To this end, consider the stereographic projection from the unit sphere minus the point

is written The inverses of these two stereographic projections are maps from the complex plane to the sphere.

, because an orientation-reversal is necessary to maintain consistent orientation on the sphere.

In more detail: The complex structure of the Riemann surface does uniquely determine a metric up to conformal equivalence.

(Two metrics are said to be conformally equivalent if they differ by multiplication by a positive smooth function.)

In particular, there is always a complete metric with constant curvature in any given conformal class.

In the case of the Riemann sphere, the Gauss–Bonnet theorem implies that a constant-curvature metric must have positive curvature

, the formula is Up to a constant factor, this metric agrees with the standard Fubini–Study metric on complex projective space (of which the Riemann sphere is an example).

denote the sphere (as an abstract smooth or topological manifold).

By the uniformization theorem there exists a unique complex structure on

, a continuous ("Lie") group that is topologically the 3-dimensional projective space

Examples of Möbius transformations include dilations, rotations, translations, and complex inversion.

In fact, any Möbius transformation can be written as a composition of these.

The Möbius transformations are homographies on the complex projective line.

Since they act on projective coordinates, two matrices yield the same Möbius transformation if and only if they differ by a nonzero factor.

If one endows the Riemann sphere with the Fubini–Study metric, then not all Möbius transformations are isometries; for example, the dilations and translations are not.

This construction is helpful in the study of holomorphic and meromorphic functions.

For example, on a compact Riemann surface there are no non-constant holomorphic maps to the complex numbers, but holomorphic maps to the complex projective line are abundant.

In quantum mechanics, points on the complex projective line are natural values for photon polarization states, spin states of massive particles of spin

, and 2-state particles in general (see also Quantum bit and Bloch sphere).