Titan (moon)

[36] Before the arrival of Voyager 1 in 1980, Titan was thought to be slightly larger than Ganymede,[18] which has a diameter 5,262 km (3,270 mi), and thus the largest moon in the Solar System.

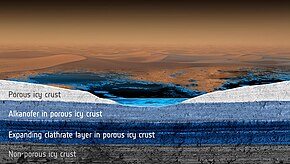

[46] The Cassini probe discovered evidence for the layered structure in the form of natural extremely-low-frequency radio waves in Titan's atmosphere.

[48] Further supporting evidence for a liquid layer and ice shell decoupled from the solid core comes from the way the gravity field varies as Titan orbits Saturn.

[55] Due to the extensive, hazy atmosphere, Titan was once thought to be the largest moon in the Solar System until the Voyager missions revealed that Ganymede is slightly larger.

[15] The hydrocarbons are thought to form in Titan's upper atmosphere in reactions resulting from the breakup of methane by the Sun's ultraviolet light, producing a thick orange smog.

[60] Energy from the Sun should have converted all traces of methane in Titan's atmosphere into more complex hydrocarbons within 50 million years—a short time compared to the age of the Solar System.

[81] Titan's atmosphere is four times as thick as Earth's,[82] making it difficult for astronomical instruments to image its surface in the visible light spectrum.

[85][86] Examination has also shown the surface to be relatively smooth; the few features that seem to be impact craters appeared to have been partially filled in, perhaps by raining hydrocarbons or cryovolcanism.

However, the first tentative detection only came in 1995, when data from the Hubble Space Telescope and radar observations suggested expansive hydrocarbon lakes, seas, or oceans.

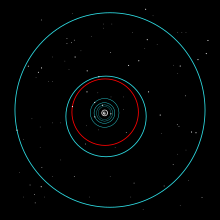

[93][94] The observed lakes and seas of Titan are largely restricted to its polar regions, where colder temperatures allow the presence of permanent liquid hydrocarbons.

Additional smaller lakes occupy Titan's polar regions, covering a cumulative surface area of 215,000 km² (83,000 sq mi).

As Titan is synchronously locked with Saturn, there exists a permanent tidal bulge of roughly 100 metres (330 ft) at the sub- and anti-Saturnian points.

[96]: 12 Through Cassini RADAR mapping of Titan's surface, numerous landforms have been interpreted as candidate cryovolcanic and tectonic features by multiple authors.

The ridges—primarily oriented east to west—are linear to arcuate in shape, with the authors of the analysis comparing them to terrestrial fold belts indicative of horizontal compression or convergence.

Cassini RADAR and VIMS imagery revealed several candidate cryovolcanic features, particularly flow-like terrains in western Xanadu and steep-sided lakes in the northern hemisphere that resemble maar craters on Earth, which are created by explosive subterranean eruptions.

Between 2005 and 2006, parts of Sotra Patera and Mohini Fluctus became significantly brighter whilst the surrounding plains remained unchanged, potentially indicative of ongoing cryovolcanic activity.

Amateur observation is difficult because of the proximity of Titan to Saturn's brilliant globe and ring system; an occulting bar, covering part of the eyepiece and used to block the bright planet, greatly improves viewing.

[130][131] A conceptual design for another lake lander was proposed in late 2012 by the Spanish-based private engineering firm SENER and the Centro de Astrobiología in Madrid.

[132] The major difference compared to the TiME probe would be that TALISE is envisioned with its own propulsion system and would therefore not be limited to simply drifting on the lake when it splashes down.

[141][142][143] The Cassini–Huygens mission was not equipped to provide evidence for biosignatures or complex organic compounds; it showed an environment on Titan that is similar, in some ways, to ones hypothesized for the primordial Earth.

[146] It has been reported that when energy was applied to a combination of gases like those in Titan's atmosphere, five nucleotide bases, the building blocks of DNA and RNA, were among the many compounds produced.

[141][149] Another model suggests an ammonia–water solution as much as 200 km (120) deep beneath a water-ice crust with conditions that, although extreme by terrestrial standards, are such that life could survive.

Assuming metabolic rates similar to those of methanogenic organisms on Earth, the concentration of molecular hydrogen would drop by a factor of 1000 on the Titanian surface solely due to a hypothetical biological sink.

McKay noted that, if life is indeed present, the low temperatures on Titan would result in very slow metabolic processes, which could conceivably be hastened by the use of catalysts similar to enzymes.

[150] In 2010, Darrell Strobel, from Johns Hopkins University, identified a greater abundance of molecular hydrogen in the upper atmospheric layers of Titan compared to the lower layers, arguing for a downward flow at a rate of roughly 1028 molecules per second and disappearance of hydrogen near Titan's surface; as Strobel noted, his findings were in line with the effects McKay had predicted if methanogenic life-forms were present.

[150][152][153] The same year, another study showed low levels of acetylene on Titan's surface, which were interpreted by McKay as consistent with the hypothesis of organisms consuming hydrocarbons.

"[152] In February 2015, a hypothetical cell membrane capable of functioning in liquid methane at cryogenic temperatures (deep freeze) conditions was modeled.

[157] Although life itself may not exist, the prebiotic conditions on Titan and the associated organic chemistry remain of great interest in understanding the early history of the terrestrial biosphere.

[158][159] On the other hand, Jonathan Lunine has argued that any living things in Titan's cryogenic hydrocarbon lakes would need to be so different chemically from Earth life that it would not be possible for one to be the ancestor of the other.

This is proposed to have been sufficient time for simple life to spawn on Earth, though the higher viscosity of ammonia-water solutions coupled with low temperatures would cause chemical reactions to proceed more slowly on Titan.