Eye movement in reading

From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, investigators used early tracking technologies to assist their observation, in a research climate that emphasised the measurement of human behaviour and skill for educational ends.

Since the mid-20th century, there have been three major changes: the development of non-invasive eye-movement tracking equipment; the introduction of computer technology to enhance the power of this equipment to pick up, record, and process the huge volume of data that eye movement generates; and the emergence of cognitive psychology as a theoretical and methodological framework within which reading processes are examined.

Sereno & Rayner (2003) believed that the best current approach to discover immediate signs of word recognition is through recordings of eye movement and event-related potential.

The first, unaided observation, yielded only small amounts of data that would be considered unreliable by today's scientific standards.

This lack of reliability arises from the fact that eye movement occurs frequently, rapidly, and over small angles, to the extent that it is impossible for an experimenter to perceive and record the data fully and accurately without technological assistance.

For example, Ibn al Haytham, a medical man in 11th-century Egypt, is reported to have written of reading in terms of a series of quick movements and to have realised that readers use peripheral as well as central vision.

"[2] His main experimental finding was that there is only distinct and clear vision at the "line of sight", the optical axis that ends at the fovea.

The subsequent decades saw more elaborate attempts to interpret eye movement, including a claim that meaningful text requires fewer fixations to read than random strings of letters.

The needle picked up the sound produced by each saccade and transmitted it as a faint clicking to the experimenter's ear through an amplifying membrane and a rubber tube.

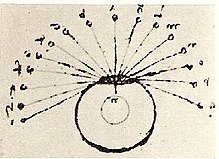

In the "Dodge technique", a beam of light was directed at the cornea, focused by a system of lenses and then recorded on a moveable photographic plate.

Erdmann & Dodge[6] used this technique to claim that there is little or no perception during saccades, a finding that was later confirmed by Utall & Smith using more sophisticated equipment.

In 1922, Schott pioneered a further advance called electro-oculography (EOG), a method of recording the electrical potential between the cornea and the retina.

Four major cognitive systems are involved in eye movement during reading: language processing, attention, vision, and oculomotor control.

The main difference between faster and slower readers is that the latter group consistently shows longer average fixation durations, shorter saccades, and more regressions.