Eye movement

Eye movements are used by a number of organisms (e.g. primates, rodents, flies, birds, fish, cats, crabs, octopus) to fixate, inspect and track visual objects of interests.

These signals travel along the optic nerve fibers to the brain, where they are interpreted as vision in the visual cortex.

Primates and many other vertebrates use three types of voluntary eye movement to track objects of interest: smooth pursuit, vergence shifts[1] and saccades.

[2] These types of movements appear to be initiated by a small cortical region in the brain's frontal lobe.

These muscles arise from the common tendinous ring (annulus of Zinn) in the orbit (eye cavity), and attach to the eyeball.

The relative contribution of the recti and oblique groups depends on the horizontal position of the eye.

In the primary position (eyes straight ahead), both of these groups contribute to vertical movement.

So the eye movement constantly changes the stimuli that fall on the photoreceptors and the ganglion cells, making the image clearer.

[14] The visual system in the brain is too slow to process that information if the images are slipping across the retina at more than a few degrees per second.

To get a clear view of the world, the brain must turn the eyes so that the image of the object of regard falls on the fovea.

To see a quick demonstration of this fact, try the following experiment: hold your hand up, about one foot (30 cm) in front of your nose.

This demonstrates that the brain can move the eyes opposite to head motion much better than it can follow, or pursue, a hand movement.

In most vertebrates (humans, mammals, reptiles, birds), the movement of different body parts is controlled by striated muscles acting around joints.

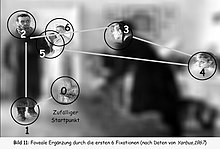

Typically, when presented with a scene, viewers demonstrate short fixation durations and long saccade amplitudes in the earlier phases of viewing an image.

This is followed by longer fixations and shorter saccades in the latter phases of scene viewing processing.

[16] It has also been found that eye movement behaviour in scene viewing differs with levels of cognitive development - fixation durations are thought to shorten and saccade amplitudes lengthen with an increase in age.

[25] Cross-culturally, it has been found that Westerners have an inclination to concentrate on focal objects in a scene, whereas East Asians attend more to contextual information.

[27] This variability is mostly due to the properties of an image and in the task being carried out, which impact both bottom-up and top-down processing.

[30] Factors which affect top-down processing (e.g. blurring) have been found to both increase and decrease fixation durations.