Ezhava

The Tirupparankunram inscription found near Madurai in Tamil Nadu and dated on palaeographical grounds to the 1st century BCE, refers to a person as a householder from Eelam (Eela-kudumpikan).

This theory is based on similarities between numerous of the customs adopted by the two groups, particularly with regard to marking various significant life stages such as childbirth and death, as well as their matrilineal practices and martial history.

Oral history, folk songs and other old writings indicate that the Thiyyas were at some point in the past members of the armed forces serving various kings, including the Zamorins of Calicut and the rulers of the Kingdom of Cochin.

A theory has been proposed for the origins of the caste system in the Kerala region based on the actions of the Aryan Jains introducing such distinctions prior to the 8th-century AD.

[19] The Ezhava used to work as agricultural labourers, small cultivators, toddy tappers and liquor businessmen; some were also involved in weaving and some practised Ayurveda.

"[23][a] A. Aiyappan, another social anthropologist and himself a member of the caste,[23] noted the mythical belief that the Ezhava brought coconut palms to the region when they moved from Ceylon.

[7] The coastal town of Alleppey became the centre of such manufacture and was mostly controlled by Ezhavas, although the lucrative export markets were accessible only through European traders, who monopolised the required equipment.

A boom in trade for these manufactured goods after World War I led to a unique situation in twentieth-century Kerala whereby there was a shortage of labour, which attracted still more Ezhavas to the industry from outlying rural areas.

The Great Depression impacted in particular on the export trade, causing a reduction in price and in wages even though production increased, with the consequence that during the 1930s many Ezhava families found themselves to be in dire financial circumstances.

The Vadakkan Pattukal ballads describe Chekavars as forming the militia of local chieftains and kings but the title was also given to experts of Kalari Payattu.

[34][page needed] Makachuttu art is popular among Ezhavas in Thiruvananthapuram and Chirayinkizhu taluks and in Kilimanoor, Pazhayakunnummal and Thattathumala regions.

Standing round a traditional lamp, the performers dance in eighteen different stages and rhythms, each phase called a niram.

Other aspirational changes included building houses in the Nair tharavad style and making claims that they had had an equal standing as a military class until the nineteenth century.

[42] A sizeable part of the Ezhava community, especially in central Travancore and in the High Ranges, embraced Christianity during the British rule, due to caste-based discrimination.

[44] The lowly status of the Ezhava meant that, as Thomas Nossiter has commented, they had "little to lose and much to gain by the economic and social changes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries".

[45] In 1896, he organised a petition of 13,176 signatories that was submitted to the Maharajah of the princely state of Travancore, asking for government recognition of the Ezhavas' right to work in public administration and to have access to formal education.

The outcome not looking to be promising, the Ezhava leadership threatened that they would convert from Hinduism en masse, rather than stay as helots of Hindu society.

[49] Eventually, in 1903, a small group of Ezhavas, led by Palpu, established Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam (SNDP), the first caste association in the region.

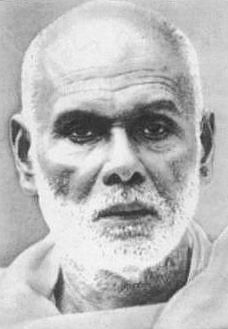

This was named after Narayana Guru, who had established an ashram from where he preached his message of "one caste, one religion, one god" and a Sanskritised version of the Victorian concept of self-help.

In Malabar, which unlike Cochin and Travancore was under direct British control,[51] the Ezhavas showed little interest in such bodies because they did not suffer the educational and employment discrimination found elsewhere, nor indeed were the disadvantages that they did experience strictly a consequence of caste alone.

[55] By mid 1904, the emerging S.N.D.P Yogam, operating a few schools, temples, and a monthly magazine announced that it would hold an industrial exhibition with its second annual general meeting in Quilon in January 1905.

Membership had reached 50,000 by 1928 and 60,000 by 1974, but Nossiter notes that, "From the Vaikom satyagraha onwards the SNDP had stirred the ordinary Ezhava without materially improving his position."

There was subsequently a radicalisation and much political infighting within the leadership as a consequence of the effects of the Great Depression on the coir industry but the general notion of self-help was not easy to achieve in a primarily agricultural environment; the Victorian concept presumed an industrialised economy.

The organisation lost members to various other groups, including the Communist movement, and it was not until the 1950s that it reinvented itself as a pressure group and provider of educational opportunities along the lines of the Nair Service Society (NSS), Just as the NSS briefly formed the National Democratic Party in the 1970s in an attempt directly to enter the political arena, so too in 1972 the SNDP formed the Social Revolutionary Party.

[50] They were considered as avarna (outside brahmanical varna system) by the Nambudiri Brahmins who formed the Hindu clergy and ritual ruling elite in late medieval Kerala.

[42][c] From their study based principally around one village and published in 2000, the Osellas noted that the movements of the late 19th- and 20th centuries brought about a considerable change for the Ezhavas, with access to jobs, education and the right to vote all assisting in creating an identity based on more on class than caste, although the stigmatic label of avarna remained despite gaining the right of access to temples.

They have campaigned for the right to record themselves as Thiyya rather than as Ezhava when applying for official posts and other jobs allocated under India's system of positive discrimination.

They claim that the stance of the government is contrary to a principle established by the Supreme Court of India relating to a dispute involving communities who were not Ezhava.

The SNDP was at that time attempting to increase its relatively weak influence in northern Kerala, where the politics of identity play a lesser role than those of class and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) has historically been a significant organisation.