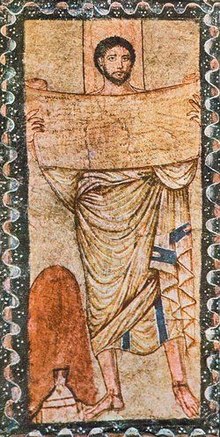

Ezra

[5][6] He is depicted as instrumental in restoring the Jewish scriptures and religion to the people after the return from the Babylonian Captivity and is a highly respected figure in Judaism.

Rabbinic tradition supports the positions that Ezra was an ordinary member of the priesthood,[19] and that he actually served as a Kohen Gadol.

The Book of Ezra describes how he led a group of Judean exiles living in Babylon to their home city of Jerusalem[21] where he is said to have enforced observance of the Torah.

[22][11] Some years later, Artaxerxes sent Nehemiah, a Jewish noble in his service, as governor in Jerusalem with the task of rebuilding the city walls.

Scholars are divided on whether it is based on Ezra–Nehemiah, or reflects an earlier literary stage before the combination of Ezra and Nehemiah accounts.

Contrariwise, Josephus does not appear to recognise Ezra-Nehemiah as a biblical book, does not quote from it, and relies entirely on other traditions in his account of the deeds of Nehemiah.

[22] The central theological themes are "the question of theodicy, God's justness in the face of the triumph of the heathens over the pious, the course of world history in terms of the teaching of the four kingdoms,[30] the function of the law, the eschatological judgment, the appearance on Earth of the heavenly Jerusalem, the Messianic Period, at the end of which the Messiah will die,[31] the end of this world and the coming of the next, and the Last Judgment.

Traditionally Judaism credits Ezra with establishing the Great Assembly of scholars and prophets, the forerunner of the Sanhedrin, as the authority on matters of religious law.

The Great Assembly is credited with establishing numerous features of contemporary traditional Judaism in something like their present form, including Torah reading, the Amidah, and celebration of the feast of Purim.

[19] In Rabbinic traditions, Ezra is metaphorically referred to as the "flowers that appear on the earth" signifying the springtime in the national history of Judaism.

According to another opinion, he did not join the first party so as not to compete, even involuntarily, with Joshua ben Jozadak for the office of High Priest of Israel.

[44][45] Many Islamic scholars and modern Western academics do not view Uzer as "Ezra"; for example, Professor Gordon Darnell Newby associates ‘Uzayr with Enoch and Metatron.

[51] There is a much clearer problem with the timeline in a story from Ezra 4, that tells of a letter that was sent to Artaxerxes asking to stop the rebuilding of the temple (which started during the reign of Cyrus and then restarted in the second year of Darius, in 521 BCE).

[52] Mary Joan Winn Leith in The Oxford History of the Biblical World believes that Ezra was a historical figure whose life was enhanced in the scripture and given a theological buildup.

The early 2nd-century BCE Jewish author Ben Sira praises Nehemiah, but makes no mention of Ezra.

According to it, Ezra was given truly exalted status by the king: he was seemingly put in charge of the entire western half of the Persian Empire, a position apparently above even the level of the satraps (regional governors).

Ezra was given vast hoards of treasure to take with him to Jerusalem as well as a letter where the king seemingly acknowledges the sovereignty of the God of Israel.

Yet, his actions in the story do not appear to be that of someone with near unlimited government power, and the alleged letter from a Persian king is written with Hebraisms and Jewish idiom.