F. Matthias Alexander

[1] His parents were the offspring of convicts transported to what was then called Van Diemen's Land for offences such as theft and destroying agricultural machinery as part of the 1830 Swing Riots in England.

In Tudor and Stuart times they were agricultural labourers, but by the eighteenth century had established themselves as carpenters and wheelwrights, some moderately wealthy, owning cottages and fields.

Alexander described himself as an agnostic, but was profoundly influenced by his Christian upbringing: his speech as an adult was peppered with biblical quotes, and he had been imbued a strong sense of right and wrong, self-discipline and personal responsibility.

[11] However, his teacher, a Scotsman named Robert Robertson, proved sympathetic, and acted as something of a father figure; he excused Alexander from daily school attendance and instead gave him lessons in the evening.

[14] According to Alexander's later account, his work at the mining company was appreciated by his employers; he took on additional jobs as a life insurance agent and a collector of rates, and was able to save £500, a considerable sum at the time.

He worked in a series of clerical jobs and took lessons from teachers such as an English actor James Cathcart, and an Australian elocutionist Fred Hill.

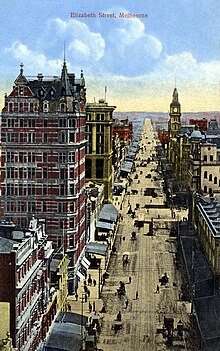

[21] Little information exists about much of Alexander's years in Melbourne,[22] but from November 1891 onwards, newspapers began to report his participation in amateur dramatic recitals, and give them positive reviews.

As described forty years later in the first chapter of his book The Use of the Self, advice from doctors and voice trainers did not have the necessary results, so he began a process of self-examination with mirrors into his speaking habits to see if he could determine the cause.

[25] Otherwise, the tour was a success, with excellent press reviews and a performance before the Governor of Tasmania in Hobart, a concert in which Robert and Edith Young, whom he had met years earlier at Watarah, also appeared.

[26] In early 1895, he set out for New Zealand where he visited various cities, giving recitals to excellent reviews and voice lessons to several prominent individuals, including Frederic Villiers and the Mayor of Auckland.

[35] Alexander arrived London in June 1904, and quickly acquired a fine wardrobe, a manservant, and a smart address at the Army & Navy Mansions in Victoria Street.

Michael Bloch, Alexander's biographer, speculates that "for some years she may have been the one person before whom he never had to pretend, with whom he was able to reminisce about his old life and friends in Australia, and who offered him intimate comforts.

[50] Alexander was proudly British; he never really felt at home in the United States, and was critical of American society, including their lack of involvement, until 1917, in the First World War.

His series of lessons resulted in long-lasting physical and intellectual improvements; more than 25 years later, in his eighties, Dewey attributed 90% of his good health to Alexander's techniques.

[53] With the help of Irene Tasker, he extensively revised the text and included new chapters on addictions, obsessive behaviours, and on the causes of the First World War, which he laid firmly at the door of Germany as a country of that has "progressed but little on the upward evolutionary stage from the state occupied by the brute beast and the savage."

However, former pupil Randolph Bourne, writing in The New Republic, while recognising the practical benefit of the technique, criticised Alexander's belief in the evolution of human society towards conscious control, a complaint echoed by the historian James Harvey Robinson in an Atlantic Monthly review.

[61] Her nephew 27-year-old ex-army officer Owen Vicary moved into the basement flat at Ashley Place with his wife Gladys (known as Jack) and their two children, and Edith appears to have developed romantic feelings for him.

[66] Following a lawsuit in 1923 resulting from an attempted return of a new car after a few weeks, Alexander transferred all his considerable assets to friends and arranged to be declared bankrupt rather than pay the debt he owed.

At the end of the war, in 1944, Dr. Dorothy Morrison (née Drew), hoping for improvement to her own 'use' (following injury in a car crash) and to the health of her disabled mother, joined the small group of Alexander's pupils at Ashley Place.

Dorothy became a close friend of Alexander's at that time, gave medical evidence at the Libel case in South Africa and soon after lived there in Johannesburg with her family.

A portrait in oil of Alexander, painted to commemorate his 80th birthday by the Australian artist Colin Colahan, was shown on the BBC's Antiques Roadshow programme in May 2013, when it was still in the possession of the son of the wife of his nephew.

[84] In 1942 Tasker's work attracted the attention of Dr Ernst Jokl, Director of Physical Education to the South African Government, and a writer on the physiology of exercise.

In March 1944 Jokl wrote an article in the South African government journal Manpower (Afrikaans Volkskragte) entitled 'Quackery versus Physical Education' which described the Technique as, among other things, 'a dangerous and irresponsible form of quackery'.

[86] In August of that year Alexander was shown the article by Tasker, and responded with a letter to the South African High Commissioner in London asking for a public withdrawal of the remarks and an apology.

[89] The trial was scheduled to be in South Africa in the autumn of 1947, but there was delay due to the defence counsel Oswald Pirow having another matter to deal with, and the case was rescheduled to the following March.

On 14 February the case Alexander v. Jokl and others,[92] an action for £5,000 damages for alleged defamation opened before Mr Justice Clayden in the Witwatersrand Local Division of the Supreme Court.

He taught people to understand their own use, to unlearn the wrong way, as in the example of a person sitting at a desk having a tendency to hunch the shoulders by tensing muscles unnecessarily.

Are you, as a trained medical man, prepared to accept as a reasonable possibility the suggestion that by the carrying out of the exercises of psycho-physical guidance by way of conscious control, one can get complete immunity against disease?"

Sir Charles Sherrington, Nobel Prize winner in physiology a strong supporter and Edward Maisel,[113] tai chi Past Grandmaster, director of the American Physical Fitness Research Institute and a member of the President's Council on Physical Fitness wrote an introduction and made the selection from F. M. Alexander's writings published as The Resurrection of the Body.

[115] In 1973 Nikolaas Tinbergen devoted about half of his Nobel Prize acceptance speech to a very favorable description of the Alexander technique and its benefits, including references to scientific evaluations.