Fakhr al-Din II

Fakhr al-Din's wealth, derived mainly from his tax farms, but also from extortion and counterfeiting, enabled him to invest in the fortifications and infrastructure needed to foster stability, order, and economic growth.

His building works included palatial government houses in Sidon, Beirut and his Chouf stronghold of Deir al-Qamar, caravanserais, bathhouses, mills, and bridges, some of which remain extant.

Christians prospered and played key roles under his rule, with his main enduring legacy being the symbiotic relationship he set in motion between Maronites and Druze, which proved foundational for the creation of a Lebanese entity.

[13] In the words of the historian Kamal Salibi, Fakhr al-Din's paternal ancestors "were the traditional chieftains of the hardy Druzes" of the Chouf, and his maternal kinsmen "were well acquainted with commercial enterprise" in Beirut (see family tree below).

Members of the community had to pretend to be of the Sunni Muslim creed to attain any official post, were occasionally forced to pay the poll tax known as jizya which was reserved for Christians and Jews, and were the target of condemnatory treatises and fatwas (religious edicts).

[16][17] During the summer 1585 expedition, hundreds of Druze elders were slain by the vizier Ibrahim Pasha and the Bedouin chief Mansur ibn Furaykh of the Beqaa Valley, and thousands of muskets were confiscated.

[27][g] According to Harris, the English traveler George Sandys, a contemporary of Fakhr al-Din, offered the "best description" of his personality, calling him "great in courage and achievements ... subtle as a fox, and a not a little inclining to the Tyrant [Ottoman sultan]".

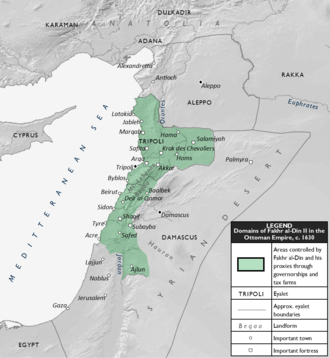

[32] Between 1591 and 1594 government records indicate that Fakhr al-Din's tax farms grew to span the Chouf, Matn, Jurd, the southern Beqaa Valley, the Shaqif and Tibnin nahiyas in Jabal Amil—in present-day South Lebanon—as well as the salt profits from the ports of Acre, Sidon, and Beirut.

[43] Fakhr al-Din, "who no doubt shared Canpolad's [Janbulad's] thirst for greater regional autonomy", according to the historian Stefan Winter,[44] had ignored government orders to join Yusuf's army.

[59] Toward the close of the 16th century, the Medici grand dukes of Tuscany had become increasingly active in the eastern Mediterranean, pushed for a new crusade in the Holy Land, and began patronizing the Maronite Christians of Mount Lebanon.

[71] The Grand Vizier demanded Fakhr al-Din disband his sekbans, surrender the strategic fortresses of Shaqif Arnun and Subayba, and execute his ally, the chieftain of Baalbek, Yunus al-Harfush; the orders were ignored.

[76] The proposal was rejected, and on 16 September, Ahmed Pasha had all the roads from Mount Lebanon into the desert blocked and the port of Sidon blockaded to prevent Fakhr al-Din's escape by land or sea.

[12] In June 1614 the Ottomans administratively reorganized Fakhr al-Din's former domains to curtail Ma'nid power, combining the sanjaks of Sidon-Beirut and Safed into a separate eyalet called Sidon and appointing to it a beylerbey from Constantinople.

[102] The beylerbeys of Damascus and Aleppo mobilized their troops in Homs and Hama, respectively, in support of Yusuf, who afterward persuaded Fakhr al-Din to accept a promissory payment of 50,000 piasters and lift the siege in March.

[105] Yusuf was dismissed again in October/November 1622 after failing to remit the promised tax payments, but refused to hand over power to his replacement Umar Kittanji, who in turn requested Fakhr al-Din's military support.

The Ma'ns thereupon moved to assume control of Ajlun and Nablus, prompting Yunus al-Harfush to call on the janissary leader Kurd Hamza, who wielded significant influence over the beylerbey of Damascus, Mustafa Pasha, to block their advance.

The reversal was linked to the successions of Sultan Murad IV (r. 1623–1640) and Grand Vizier Kemankeş Ali Pasha, the latter of whom had been bribed by Fakhr al-Din's agent in Constantinople to restore the Ma'ns to their former sanjaks.

Fakhr al-Din arrived in Qabb Ilyas on 22 October, and immediately moved to restore lost money and provisions from the Palestine campaign by raiding the nearby villages of Karak Nuh and Sar'in, both held by the Harfushes.

[134] By the early 1630s, Muhibbi noted that Fakhr al-Din had captured many places around Damascus, controlled thirty fortresses, commanded a large army of sekbans, and that the "only thing left for him to do was to claim the Sultanate".

[150] Among the contributing factors were the unstable relations between Constantinople and the Levantine provinces with every change of sultan and grand vizier; Fakhr al-Din permanently fell out of imperial favor with Murad IV's accession in 1623.

[139] Sandys, who visited Sidon in 1611, observed that Fakhr al-Din had amassed a fortune "gathered by wiles and extortion" from locals and foreign merchants, counterfeited Dutch coins, and was a "severe justice", who restored the ruined structures and repopulated the once-abandoned settlements in his domains.

[156] In Safed, where political and economic conditions in the sanjak had deteriorated in the years preceding Fakhr al-Din's appointment, the imperial authorities lauded him in 1605 for "guarding the country, keeping the Bedouins in check, ensuring the welfare and tranquility of the population, promoting agriculture, and increasing prosperity",[32] a state of affairs affirmed by Khalidi.

[162] In 1630, the Medici granted Fakhr al-Din's request to post a permanent representative to Sidon by dispatching an unofficial consul who operated under the French flag to avoid violating Ottoman capitulation agreements.

[155] In the assessment of Salibi, at a time when the Empire "was sinking to destitution because of its failure to adapt to changing circumstances, the realm of Faḫr al-dīn Maʿn [sic], in the southern Lebanon [range] and Galilee, attracted attention as a tiny corner into which the silver of Europe flowed".

[171] Harris places Fakhr al-Din, along with the heads of the Janbulad, Assaf, Sayfa, and Turabay families, in a category of late 16th–early 17th-century Levantine "super chiefs ... serviceable for the Ottoman pursuit of 'divide and rule' ...

In 1660, the Ottomans reestablished the Sidon Eyalet and in 1697, awarded Fakhr al-Din's grandnephew Ahmad ibn Mulhim the iltizam of its mountain nahiyas of the Chouf, Gharb, Jurd, Matn, and Keserwan.

Fakhr al-Din himself has been adopted by a number of Maronite nationalists as a member of the religious group, citing the refuge he may have taken with the Khazen family in the Keserwan during his adolescence, or claiming that he had embraced Christianity at his deathbed.

[185] Nonetheless, the modern historian Elie Haddad holds that his communications with Tuscany indicate that Fakhr al-Din's primary concern was utilitarian, namely the defense of his territory, facilitation of movement for his soldiers, and raising the living standards of the inhabitants.

[189] Other than the entrance of the building, which is characterized by ablaq masonry and a type of ornamented vaulting known as muqarnas, the rest of the original structure had been gradually replaced through the early 19th century, when it was converted into a school; the courtyard is now a schoolyard and the garden is a playground.

[192][n] He initially endowed the family's properties in Sidon, sixty-nine in total and mostly owned by Fakhr al-Din, his son Ali, and brother Yunus, in an endowment—known as a waqf—administered from Damascus for the benefit of the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina.