Operation Barbarossa

The operation, code-named after the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa ("red beard"), put into action Nazi Germany's ideological goals of eradicating communism and conquering the western Soviet Union to repopulate it with Germans under Generalplan Ost, which planned for the extermination of the native Slavic peoples by mass deportation to Siberia, Germanisation, enslavement, and genocide.

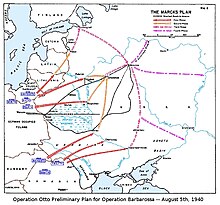

Following the Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina in July 1940, the German High Command began planning an invasion of the country, which was approved by Adolf Hitler in December.

[39] As early as 1925, Adolf Hitler vaguely declared in his political manifesto and autobiography Mein Kampf that he would invade the Soviet Union, asserting that the German people needed to secure Lebensraum ('living space') to ensure the survival of Germany for generations to come.

[43] Accordingly, it was a partially secret but well-documented Nazi policy to kill, deport, or enslave the majority of Russian and other Slavic populations and repopulate the land west of the Urals with Germanic peoples, under Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East).

"[45] While older histories tended to emphasize the myth of the "clean Wehrmacht," upholding its honor in the face of Hitler's fanaticism, the historian Jürgen Förster notes that "In fact, the military commanders were caught up in the ideological character of the conflict, and involved in its implementation as willing participants".

"[72] There would be no "long-term agreement with Russia" given that the Nazis intended to go to war with them; but the Soviets approached the negotiations differently and were willing to make huge economic concessions to secure a relationship under general terms acceptable to the Germans just a year before.

[90] Hitler, solely focused on his ultimate ideological goal of eliminating the Soviet Union and Communism, disagreed with economists about the risks and told his right-hand man Hermann Göring, the chief of the Luftwaffe, that he would no longer listen to misgivings about the economic dangers of a war with the USSR.

Neither Hitler nor the General Staff anticipated a long campaign lasting into the winter and therefore, adequate preparations such as the distribution of warm clothing and winterisation of important military equipment like tanks and artillery, were not made.

[93] Nazi policy aimed to destroy the Soviet Union as a political entity in accordance with the geopolitical Lebensraum ideals for the benefit of future generations of the "Nordic master race".

[77] In 1941, Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg—later appointed Reich Minister of the Occupied Eastern Territories—suggested that conquered Soviet territory should be administered in the following Reichskommissariate ('Reich Commissionerships'): German military planners also researched Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia.

[102][103] This belief later led to disputes between Hitler and several German senior officers, including Heinz Guderian, Gerhard Engel, Fedor von Bock and Franz Halder, who believed the decisive victory could only be delivered at Moscow.

[99] Army Group South was to strike the heavily populated and agricultural heartland of Ukraine, taking Kiev before continuing eastward over the steppes of southern USSR to the Volga with the aim of controlling the oil-rich Caucasus.

[129] The German forces in the rear (mostly Waffen-SS and Einsatzgruppen units) were to operate in conquered territories to counter any partisan activity in areas they controlled, as well as to execute captured Soviet political commissars and Jews.

[77] On 17 June, Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) chief Reinhard Heydrich briefed around thirty to fifty Einsatzgruppen commanders on "the policy of eliminating Jews in Soviet territories, at least in general terms".

[137] But in spite of efforts to ensure the political subservience of the armed forces, in the wake of Red Army's poor performance in Poland and in the Winter War, about 80 percent of the officers dismissed during the Great Purge were reinstated by 1941.

The debate began in the late 1980s when Viktor Suvorov published a journal article and later the book Icebreaker in which he claimed that Stalin had seen the outbreak of war in Western Europe as an opportunity to spread communist revolutions throughout the continent, and that the Soviet military was being deployed for an imminent attack at the time of the German invasion.

[173] Suvorov's thesis was fully or partially accepted by a limited number of historians, including Valeri Danilov, Joachim Hoffmann, Mikhail Meltyukhov, and Vladimir Nevezhin, and attracted public attention in Germany, Israel, and Russia.

[180] The debate on whether Stalin intended to launch an offensive against Germany in 1941 remains inconclusive but has produced an abundance of scholarly literature and helped to expand the understanding of larger themes in Soviet and world history during the interwar period.

[197] At around 03:15 on 22 June 1941, the Axis Powers commenced the invasion of the Soviet Union with the bombing of major cities in Soviet-occupied Poland[198] and an artillery barrage on Red Army defences on the entire front.

[204] In Germany, on the morning of 22 June, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels announced the invasion to the waking nation in a radio broadcast with Hitler's words: "At this moment a march is taking place that, for its extent, compares with the greatest the world has ever seen.

[253] In addition to strained logistics, poor roads made it difficult for wheeled vehicles and foot infantry to keep up with the faster armoured spearheads, and shortages in boots and winter uniforms were becoming apparent.

Nowhere was the Soviet levée en masse spirit stronger in resisting the Germans than at Leningrad where reserve troops and freshly improvised Narodnoe Opolcheniye units, consisting of worker battalions and even schoolboy formations, joined in digging trenches as they prepared to defend the city.

The United States of America applied diplomatic pressure on Finland not to disrupt Allied aid shipments to the Soviet Union, which caused the Finnish government to halt the advance on the Murmansk railway.

[269] Russian peasants began fleeing ahead of the advancing German units, burning their harvested crops, driving their cattle away, and destroying buildings in their villages as part of a scorched-earth policy designed to deny to the Nazi war machine needed supplies and foodstuffs.

[331] Again, the Germans quickly overran great expanses of Soviet territory, but they failed to achieve their ultimate goal of the oil fields of Baku, culminating in their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad in February 1943 and withdrawal from the Caucasus.

[335] Employing increasingly ambitious and tactically sophisticated offensives, along with making operational improvements in secrecy and deception, by the summer of 1944, the Red Army was eventually able to regain much of the area previously conquered by the Germans.

[348][349] On the eve of the invasion, German soldiers were informed that their battle "demands ruthless and vigorous measures against Bolshevik inciters, guerrillas, saboteurs, Jews and the complete elimination of all active and passive resistance".

[363][364][365] The German-Finnish blockade cut off access to food, fuel and raw materials, and rations reached a low, for the non-working population, of 4 ounces (110 g) (five thin slices) of bread and a little watery soup per day.

[368] Historian Hannes Heer relates that in the world of the eastern front, where the German army equated Russia with Communism, everything was "fair game"; thus, rape went unreported unless entire units were involved.

[370] Historian Birgit Beck emphasizes that military decrees, which served to authorise wholesale brutality on many levels, essentially destroyed the basis for any prosecution of sexual offenses committed by German soldiers in the East.