Fall of the Western Roman Empire

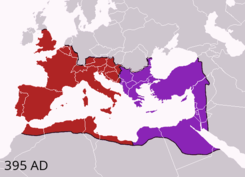

[14][15]: 3, 4 A synthesis by Harper (2017) gave four decisive turns of events in the transformation from the height of the empire to the early Middle Ages: The loss of centralized political control over the West, and the lessened power of the East, are universally agreed, but the theme of decline has been taken to cover a much wider time span than the hundred years from 376.

As one convenient marker for the end, 476 has been used since Gibbon, but other key dates for the fall of the Roman Empire in the West include the Crisis of the Third Century, the Crossing of the Rhine in 406 (or 405), the sack of Rome in 410, and the death of Julius Nepos in 480.

The emperors, anxious for their personal safety and the public peace, were reduced to the base expedient of corrupting the discipline which rendered them alike formidable to their sovereign and to the enemy; the vigour of the military government was relaxed, and finally dissolved, by the partial institutions of Constantine; and the Roman world was overwhelmed by a deluge of Barbarians.

[14][28] While Alexander Demandt enumerated 210 different theories on why Rome fell, twenty-first century scholarship classifies the primary possibilities more concisely:[29][30] A recent summary interprets disease and climate change as important drivers of the political collapse of the empire.

[68] The devastations of the barbarians impoverished and depopulated the [Western] frontier provinces, and their unceasing pressure imposed on the empire a burden of defense which overstrained its administrative machinery and its economic resources.

The literate elite considered theirs to be the only worthwhile form of civilization, giving the Empire ideological legitimacy and a cultural unity based on comprehensive familiarity with Greek and Roman literature and rhetoric.

At a lower level within the army, connecting the aristocrats at the top with the private soldiers, a large number of centurions were well-rewarded, literate, and responsible for training, discipline, administration, and leadership in battle.

Ammianus described some who enriched from the offerings of matrons, ride seated in carriages, wearing clothing chosen with care, and serve banquets so lavish that their entertainments outdo the tables of kings.

[85] Ammianus Marcellinus, himself a professional soldier, repeats longstanding observations about the superiority of contemporary Roman armies being due to training and discipline, not to individual size or strength.

[87] Despite a possible decrease in the Empire's ability to assemble and supply large armies,[88] Rome maintained an aggressive and potent stance against perceived threats almost to the end of the fourth century.

In 378, Valens attacked the invaders with the Eastern field army, now perhaps 20,000 men, probably much fewer than the forces that Julian had led into Mesopotamia a little over a decade before, and possibly only 10% of the soldiers nominally available in the Danube provinces.

(In contrast, during the Cimbrian War, the Roman Republic, controlling a smaller area than the western Empire, had been able to reconstitute large regular armies of citizens after greater defeats than Adrianople.

[126][129][128][a] Theodosius had to face a powerful usurper in the West; Magnus Maximus declared himself Emperor in 383, stripped troops from the outlying regions of Roman Britain (probably replacing some with federate chieftains and their war-bands) and invaded Gaul.

In some Christian holy places, Alaric's men even refrained from wanton violence, and Jerome tells the story of a virgin who was escorted to a church by the invaders, after they had given her mother a beating from which she later died.

On hearing that Rome itself had fallen, he breathed a sigh of relief: At that time they say that the Emperor Honorius in Ravenna received the message from one of the eunuchs, evidently a keeper of the poultry, that Roma had perished.

[201] For the next few years these barbarian tribes wandered in search of food and employment, while Roman forces fought each other in the name of Honorius and a number of competing claimants to the imperial throne.

Constantine's power reached its peak in 409 when he controlled Gaul and beyond, he was joint consul with Honorius[203] and his magister militum Gerontius defeated the last Roman force to try to hold the borders of Hispania.

Although Constantius rebuilt the western field army to some extent, he did so only by replacing half of its units (vanished in the wars since 395) by re-graded barbarians, and by garrison troops removed from the frontier.

But it marked huge losses of territory and of revenue; Rutilius travelled by ship past the ruined bridges and countryside of Tuscany, and in the west the river Loire had become the effective northern boundary of Roman Gaul.

After some months of intrigue, the patrician Castinus installed Joannes as Western Emperor, but the Eastern Roman government proclaimed the child Valentinian III instead, his mother Galla Placidia acting as regent during his minority.

[238] He identified many deficiencies in the military, especially mentioning that the soldiers were no longer properly equipped:From the foundation of the city till the reign of the Emperor Gratian, the foot wore cuirasses and helmets.

Although these men differ in customs and language from those with whom they have taken refuge, and are unaccustomed too, if I may say so, to the nauseous odor of the bodies and clothing of the barbarians, yet they prefer the strange life they find there to the injustice rife among the Romans.

[240] Gildas, a 6th-century monk and author of De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, wrote that In the respite from devastation, the island [Britain] was so flooded with abundance of goods that no previous age had known the like of it.

[241] The Visigoths passed another waymark on their journey to full independence; they made their own foreign policy, sending princesses to make (rather unsuccessful) marriage alliances with Rechiar of the Sueves and with Huneric, son of the Vandal king Genseric.

Huns attacked the Eastern empire,[244] and the troops, which had been sent against Genseric, were hastily recalled from Sicily; the garrisons, on the side of Persia, were exhausted; and a military force was collected in Europe, formidable by their arms and numbers, if the generals had understood the science of command, and the soldiers the duty of obedience.

Despite admitting that the peasantry could pay no more, and that a sufficient army could not be raised, the imperial regime protected the interests of landowners displaced from Africa and allowed wealthy individuals to avoid taxes.

An outbreak of disease in his army, lack of supplies, reports that Eastern Roman troops were attacking his noncombatant population in Pannonia, and, possibly, Pope Leo I's plea for peace induced him to halt this campaign.

The Anonymus Valesianus wrote that Odoacer, "taking pity on his youth" (he was then 16 years old), spared Romulus' life and granted him an annual pension of 6,000 solidi before sending him to live with relatives in Campania.

[283] The civitates of Britannia continued to look to their own defence as Honorius had authorized; they maintained literacy in Latin and other identifiably Roman traits for some time although they sank to a level of material development inferior even to their pre-Roman Iron Age ancestors.

[287] The Western barbarians lost much of these higher cultural practices, but their redevelopment in the Middle Ages by polities aware of the Roman achievement formed the basis for the later development of Europe.

HONORI

MARIA

SERHNA

VIVATIS

STELICHO .

The letters form a Christogram .