Fall of Singapore

Financial constraints had hampered construction efforts during the intervening period and shifting strategic circumstances had largely undermined the key premises behind the strategy by the time war had broken out in the Pacific.

[22] The Imperial Japanese Army Air Force was more numerous and better trained than the second-hand assortment of untrained pilots and inferior Commonwealth equipment remaining in Malaya, Borneo and Singapore.

[27][e] At Bakri, from 18 to 22 January, the Australian 2/19th and 2/29th battalions and the 45th Indian Brigade (Lieutenant Colonel Charles Anderson) repeatedly fought through Japanese positions before running out of ammunition near Parit Sulong.

[35][36] During the weeks preceding the invasion, Commonwealth forces suffered a number of both subdued and openly disruptive disagreements amongst its senior commanders,[37] as well as pressure from Australian Prime Minister John Curtin.

Lionel Wigmore, the Australian official historian of the Malayan campaign, wrote Only one of the Indian battalions was up to numerical strength, three (in the 44th Brigade) had recently arrived in a semi-trained condition, nine had been hastily reorganised with a large intake of raw recruits, and four were being re-formed but were far from being fit for action.

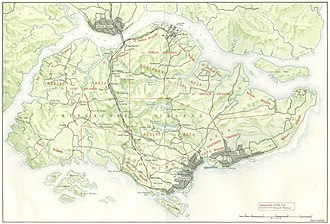

[43]Percival gave Major-General Gordon Bennett's two brigades from the 8th Australian Division responsibility for the western side of Singapore, including the prime invasion points in the northwest of the island.

[49] From aerial reconnaissance, scouts, infiltrators and observation from high ground across the straits (such as at Istana Bukit Serene and the Sultan of Johor's palace), Japanese commander General Tomoyuki Yamashita and his staff gained excellent knowledge of the Commonwealth positions.

[50][51] Although his military advisors judged that Istana Bukit Serene was an easy target, Yamashita was confident that the British Army would not attack the palace because it belonged to the Sultan of Johor.

[53][54][g] Percival incorrectly guessed that the Japanese would land forces on the north-east side of Singapore, ignoring advice that the north-west was a more likely direction of attack (where the Straits of Johor were the narrowest and a series of river mouths provided cover for the launching of water craft).

To compound matters, Percival had ordered the Australians to defend forward so as to cover the waterway, yet this meant they were immediately fully committed to any fighting, limiting their flexibility, whilst also reducing their defensive depth.

[60] In comparison, following the withdrawal, Percival had about 85,000 men at his disposal, although 15,000 were administrative personnel, while large numbers were semi-trained British, Indian and Australian reinforcements that had only recently arrived.

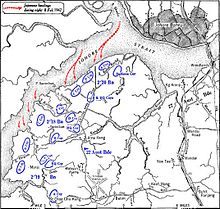

[62] The Australians requested the shelling of these positions to disrupt the Japanese preparations but the patrol reports were later ignored by Malaya Command as being insignificant, based upon the belief that the real assault would come in the north-eastern sector, not the north-west.

The resistance put up by the company from the 2/19th pushed the follow-on waves of Japanese craft to land around the mouth of Murai River, which resulted in them creating a gap between the 2/19th and 2/18th battalions.

Over the course of two hours, the three Australian battalions that had been engaged sought to regroup, moving back east from the coast towards the centre of the island, which was completed mainly in good order.

For the rest of December there were false alerts and several infrequent and sporadic hit-and-run attacks on outlying military installations such as the Naval Base but no raids on Singapore City.

[74] As the Japanese army advanced towards Singapore Island, the day and night raids increased in frequency and intensity, resulting in thousands of civilian casualties, up to the time of the British surrender.

[80] By the time of the invasion, only ten Hurricanes of 232 Squadron, based at RAF Kallang, remained to provide air cover for the Commonwealth forces on Singapore.

In the first encounter, the last ten Hurricanes were scrambled from Kallang Airfield to intercept a Japanese formation of about 84 aircraft, flying from Johor to provide air cover for their invasion force.

[84] A squadron of Hurricane fighters took to the skies on 9 February but was then withdrawn to the Netherlands East Indies and after that no Commonwealth aircraft were seen again over Singapore; the Japanese had achieved air supremacy.

[85] On the evening of 10 February, General Archibald Wavell, commander of ABDA, ordered the transfer of all remaining Commonwealth air force personnel to the Dutch East Indies.

[88] Throughout the day, the 44th Indian Infantry Brigade, still holding its position on the coast, began to feel pressure on its exposed flank and after discussions between Percival and Bennett, it was decided that they would have to retire eastwards to maintain the southern part of the Commonwealth line.

[111] The counter-attack was repulsed by the Imperial Guards and the 27th Australian Brigade was split in half on either side of the Bukit Timah Road with elements spread as far as the Pierce Reservoir.

The next day, as the situation worsened for the Commonwealth, they sought to consolidate their defences; during the night of 12/13 February, the order was given for a 28 mi (45 km) perimeter to be established around Singapore City at the eastern end of the island.

[121] An Air Liaison Officer with the British Indian Army, Heenan had been recruited by Japanese military intelligence and had used a radio to assist them in attacking Commonwealth airfields in northern Malaya.

[134] Throughout the night of 14/15 February, the Japanese continued to press against the Commonwealth perimeter, and though the line largely held, the military supply situation was rapidly deteriorating.

The water system was badly damaged and supply was uncertain, rations were running low, petrol for military vehicles was all but exhausted, and there was little ammunition left for the field artillery and anti-aircraft guns, which were unable to disrupt the Japanese air attacks causing many casualties in the city centre.

[138] In analysing the campaign, Clifford Kinvig, a senior lecturer at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, blamed the commander of the 27th Infantry Brigade, Brigadier Duncan Maxwell, for his defeatist attitude and not properly defending the sector between the Causeway and the Kranji River.

[157] While impressed with Japan's quick succession of victories, Adolf Hitler reportedly forbade Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop from issuing a congratulatory communique.

Thousands of others were transported by sea to other parts of Asia, including Japan, to be used as forced labour on projects such as the Siam–Burma Death Railway and Sandakan airfield in North Borneo.

The Dutch KNIL garrisons stationed on Batam had already abandoned the island on 14 February 1942, after hearing reports of the impending total collapse of Singapore across the strait.